After more than two decades silence, a journalist who was once expelled from the Soviet Union has made contact. With a resurgent Russia back on the scene, his knowledge of how things used to be in Moscow could once again be useful.

But why was he so silent for so long? Can this really be the same man? And what do the things he learnt nearly 40 years ago tell us about Russia today?

You could be forgiven for thinking that these opening sentences sound like the back cover blurb for Fatal Ally. They are not. They are about its author, Tim Sebastian.

Tim Sebastian is a highly successful journalist and former BBC Moscow correspondent, who was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1985, just as the Gorbachev era was getting underway. For British TV viewers of a certain age, Sebastian was one of the faces of Communism’s end period.

(Russia in Fiction always associates Tim Sebastian with reporting on the Solidarity trade union in Poland in the early 1980s, but that might be because he used to sport a moustache that gave him an uncanny similarity to Solidarity’s leader, Lech Wałęsa.)

Sebastian wrote a series of Russia-related thrillers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the editions shown here going all-in on the silhouette cover front.

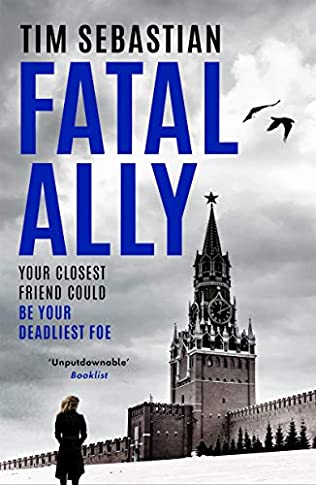

His last novel —the non-Russia-related Ultra— was published in 1997. After that, silence. Until Russia in Fiction noticed a few weeks back that a new Tim Sebastian novel had been published, called Fatal Ally and sporting a ‘silhouette, Red Square’ cover.

We had to read it. We had to screw up our planned reviewing schedule and chuck it in the bin. There are questions that need answering. Why has Sebastian returned? Is Fatal Ally any good? And what does this new novel say about Russia in its fiction?

The actual blurb for Fatal Ally on Amazon goes like this:

After five years’ silence, a British intelligence asset has made contact from Moscow. Claiming to be in possession of an explosive piece of information, he wishes to defect to the West. The carefully-planned operation however goes catastrophically wrong, the would-be defector ruthlessly betrayed by a rogue element at the highest level of US government. As a result, MI6’s Margo Lane is ordered to deliver a message the White House won’t forget.

Despite not having been heard from, as a thriller-writer, since 1997, Tim Sebastian’s return to the genre is an accomplished piece of plotting written in a contemporary style.

Russia in Fiction has most of Sebastian’s previous novels on our shelf and enjoyed them back in the day. Like many a journalist-turned-thriller-writer, Tim Sebastian knew the intricacies of political intrigue and drew on the on-site knowledge gained from his postings.

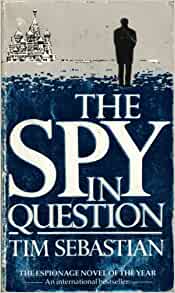

Sebastian’s first novel, The Spy in Question (1988) is an enjoyable espionage thriller set largely in Moscow, about a KGB agent spying for the West who comes under suspicion.

The Spy in Question is very much of its genre and time —mention of ‘Sad Sam’, the apartment block that housed Westerners on a Moscow posting and is noted in our review of Anne Telscombe’s The Listener (1968); the seemingly obligatory descriptions of shopping in a time of shortages; and depictions of Soviet-era public toilets that reminded Russia in Fiction both of our own experience and of similar representations in Joseph Finder’s The Moscow Club (1991)

… little more than a series of troughs, evil-smelling, overflowing with human wastage. It wasn’t a place to stay and no one took notice of anything. Normal inhibitions were suspended.

The Spy in Question, p. 39

Saviour’s Gate (1991) imagines an escape scenario for a reformist Soviet General Secretary threatened with a coup.

Last Rights (1993) tells the story of the son of a Soviet émigrée who suddenly finds himself, as the Cold War ends, jolted from his London life into a fast-moving manhunt that takes him to the chaos of post-Soviet Russia.

‘… welcome to the madhouse. Don’t stay too long!’

The station was crowded —just two platforms— and mankind and his boxes piled onto both of them …

‘What time is the train to Moscow?’ I shouted over the noise …

‘What train? … What do you want to go to Moscow for? … They’ll kill you and rob you there. Much better stay put.’

Last Rights, pp. 215-216

All are familiar portrayals of Russia in fiction for the years in question.

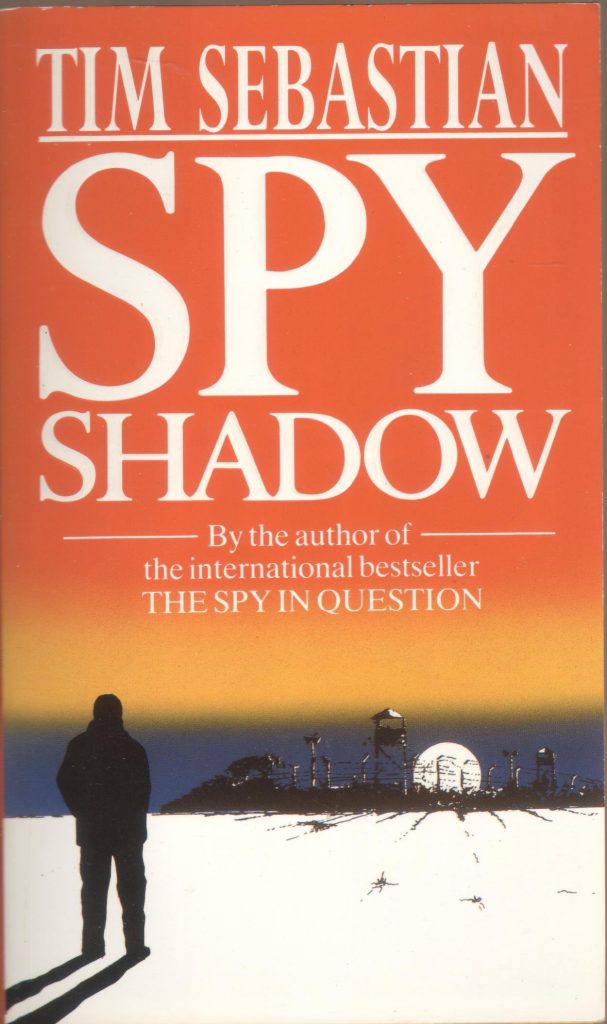

Tim Sebastian’s other novels from those years see aspects of East-West relations covered with less of a Russia-focus and more of an Eastern European setting in Spy Shadow (1989), Exit Berlin (1992), and The Memory Church (1993).

We notice that the first three of Tim Sebastian’s novels are to be re-issued next year, with the soubriquet ‘the Cold War collection’, and sporting currently fashionable, small silhouette, black and white, cover designs (see for example, Charles Cumming’s BOX 88 and JUDAS 62).

Moving beyond the Cold War, Special Relations (1994) turned its attention to US-UK relations, with a Soviet-related element, before Sebastian —like many a political thriller writer wondering what was next after the collapse of the Soviet Union— started looking around for other areas of international intrigue and unrest in which to set his novels. He alighted on the Yugoslav crisis (War Dance, 1995) and the first Gulf War and its aftermath (Ultra, 1997).

And then, after 1997, silence. Until Fatal Ally, published in 2019.

(Although confusingly, the copyright page of our edition of Fatal Ally says both ‘first published in 2019’ by the London-based publisher Severn House, and ‘first published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2021’ by the Edinburgh-based Canongate books. Certainly, Russia in Fiction had not come across it until a few weeks ago.)

Back in the novelist’s harness, Tim Sebastian continues to write a gripping story whilst having updated his writing style to the much snappier mode that is more common in contemporary thriller writing than it used to be. Short chapters, succinct dialogue, fast-moving.

Sebastian’s heroine is a British MI6 agent, Margo Lane; a female lead in the mode of Stella Rimington’s Liz Carlyle or Tom Bradby’s Kate Henderson. All-action figures, but with a hinterland to acknowledge that family life and relationships carry on, or not, even for spies.

The plot of Fatal Ally moves along at a fair pace, with the first half of the book in particular being Russia-in-fiction territory, as increasingly dissolute former KGB man, Arkady Mazurin, tries to get out of Russia and buy himself a new identity in the West, in the UK to be precise, on the back of some information and evidence that he thinks valuable.

And what is this evidence? It is covertly recorded footage, three decades old, of the Deputy Mayor of Leningrad extorting money from City officials, who in turn make that money back in bribes; except on this one occasion, captured by a surveillance camera, an official stands up to the Deputy Mayor, and as a result is strangled with wire flex as he calmly watches on.

Those who know Russia also know that Vladimir Putin was Deputy Mayor of St Petersburg in the early 1990s; although Fatal Ally is not so crass as to mention Putin anywhere in the text. Instead we get:

That film from Leningrad would, he [Arkady] was certain, buy him his ticket to London and ensure he was treated with the respect his talents deserved.

Not because the British would be interested in a sordid murder thirty years before in Russia’s second city – but because the deputy mayor, pictured in that film, had done so surprisingly well in his subsequent career.

Fatal Ally, Chapter 8

That Arkady’s planned defection to the West does not go according to plan turns out to be because an official in the United States is not playing straight with the British — hence the titular ‘fatal ally’ — leading to a well-written scene as Arkady seeks to board his plane at Moscow’s Domodedevo airport.

As the novel progresses, the scene shifts away from Moscow to a denouement played out in Syria, near the Jordanian border, focusing on the US-UK relationship, albeit with Russia remaining a tangential player in the novel’s plot.

As a thriller then, Fatal Ally ticks the boxes of being a well-written and fast-paced page-turner.

What about how Russia is portrayed in the fiction? In short, miserably.

We are used in thriller writing of the past decade to seeing a return to Soviet-era tropes (see our review of Jason Matthews’s Red Sparrow for discussion of a particularly egregious example), and the adoption of what we have taken to calling a ‘big, bad Russia’ depiction. And up to a point, this is an understandable simplification in the world of international political thrillers. But Russia in Fiction is not sure that we have come across any writer as unremittingly downbeat about Russia as Tim Sebastian.

In Moscow’s Donskoy cemetery, Margo Lane sees some old people weeping. Not that unusual a cemetery experience, one would have thought; except, it being Tim Sebastian’s Russia, these old people are confronting

… true despair. The kind that had sat inside them for decades, spawned by unimaginable evil.

Fatal Ally, Chapter 3

Tim Sebastian repeatedly delivers no-room-for-nuance and almost apocalyptically negative generalisations about Russia.

Russia was and always had been about betrayal. (Chapter 20)

To encounter a stranger in Russia is a cold and unfriendly process. There is very little neutral ground to meet on and no desire or time for pleasantries. (Chapter 20)

Centuries of brutality and repression had built a country where you sold out your friends and family and acquaintances before they turned around —out of choice or necessity— and did it to you. (Chapter 20)

“I’m prepared for anything, however bad. That’s what this country did to me. Turned me into the kind of person who’s always waiting for disaster. And not just me. Tens of millions of us. This is what they did. Whenever something good happened, we always waited for the bash on the head or the punch in the face. We’re Russians. Our life is hard. But we make it like that. We’re stupid people who create our own problems and then battle with them unsuccessfully all our life. How much more idiotic can you get?” (Chapter 26)

As always the ring road was crowded with late shoppers and people heading for their weekend dachas. What a quaint image, he thought, but so unlike the real Russia! Oh yes, they drove out in their hundreds of thousands to their retreats —anything from shacks to country estates— but they all did the same when they got there: drank themselves senseless, only to return with dead eyes and blotchy skin from a weekend they could barely remember. No wonder so many died early. (Chapter 37)

… someone would come. Maybe five or six someones, breaking down her door in the hours to come and inquiring about what her ‘traitor husband’ had been intending to do. They’d beat her first. That was the way such ‘inquiries’ began. And then the interrogation, on and on, hour after hour. (Chapter 40)

Most cities just sleep at night, she thought. This one [Moscow] dies. (Chapter 40)

Violence was the default setting in Russia. (Chapter 40)

She couldn’t look at the city, couldn’t look at people who lived and died in cruelty and violence and thought it was normal. Accepted it, made it normal, told lies to themselves, pretended everything was fine and taught their children, generation after generation, to close their eyes and do the same. (Chapter 40)

Fatal Ally

Blimey. You can plead a few caveats around how exaggeration is a part of thriller-writing, or how some of the above is the voice of particular characters rather than the author. But still, these quotes offer an unremittingly bleak view of a country and a people.

Fatal Ally represents an unexpected return for a good thriller writer, more than two decades on from his previous novel. As a thriller it is a well-plotted story that ratchets up the tension and keeps the pages turning.

But its portrayal of Russia? An all shade and no light, nuance-free zone, as if contemporary Russia was the Soviet Union, even Stalin’s Soviet Union, and populated by a uniformly miserable subjected people. To be frank, it is one of the most dismal portrayals of Russia in fiction that Russia in Fiction has ever come across; and only a small amount of it can be deemed necessary for the plot. Nice to have you back, Mr Sebastian. But do lighten up a little …