Charles Cumming is at the forefront of contemporary British thriller writers, and is on a bit of a roll at the moment. JUDAS 62 is his eleventh novel. The majority of these —with The Trinity Six being one of three exceptions— are not really Russia-in-fiction territory. But JUDAS 62 most definitely is.

‘Big bad Russia’ is back as the main enemy, and a large part of JUDAS 62 is set in the Russian city of Voronezh in 1993.

Russia in Fiction has set the scene for this review by raving about Charlotte Hobson’s superb memoir Black Earth City in our preceding post. Voronezh is a city we know very well, and the temporal setting of JUDAS 62 is not too far distant from the time that I lived there. Though the distance between 1988 and 1993 should really be measured politically as well as in years; in that five year period the city of Voronezh moved from one country, the Soviet Union, to another, the Russian Federation; and from Communist rule to the chaos of the wannabe-democracy that was the newly independent post-Communist Russia during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin.

Or, as Cumming pithily puts it

Then Gorbachev goes to his dacha, Yeltsin stands on his tank and the Soviet Union collapses.

JUDAS 62, Chapter 9

Not one of those authors who uses the same character in all of his novels, Cumming laudably mixes things up a little. Across his back catalogue, a couple of his early books feature Alec Milius as the lead character, and a little later he wrote a trilogy around the lead figure of Thomas Kell.

JUDAS 62 is the second in what Russia in Fiction is guessing might well be another trilogy, this time with Lachlan Kite as the central protagonist.

(The guess around this being a trilogy is part-wishful thinking, because we want it to be so, and part supposition drawing on the unresolved character of Kite’s former lover Martha).

Lachlan ‘Lockie’ Kite was, like Charles Cumming, educated at one of England’s leading public schools (Eton in the real world, fictionalised as Alford) and at the University of Edinburgh. His route into the security services is set out in the excellent, but not Russia-related, BOX 88 (2020).

BOX 88 has parallel and connected plot-lines, as the first operation of Lachlan Kite’s secret career, in 1989, is set out alongside a present day operation which draws on the characters and consequences of its precursor.

The same twin track approach works again in JUDAS 62, as Kite’s undercover extraction of a Russian biological weapons specialist from Voronezh in 1993 results in putative biological revenge by a resurgent Russia in the present day.

The titles of these Lachlan Kite novels elucidate by explanation. In JUDAS 62, the Russian security services are depicted as on the hunt for traitors to assassinate, with their names being on a ‘Judas list’ that comes into Kite’s hands. Earlier names on the list include Litvinenko and Skripal. Kite is seeking to protect Judas number 62.

And the organisation for which Kite works is not quite the British security services, but rather an off-the-books organisation called BOX 88, a joint US-UK security body with immense resources and world-wide staffing that somehow has managed to remain unknown to the wider world, and is only a rumour to its increasingly scrutinised colleagues in MI5, MI6, and the CIA.

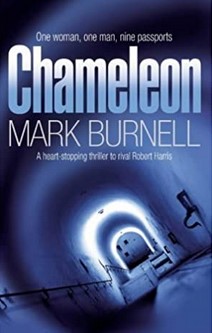

A little far-fetched perhaps, but hey, this is fiction, and there is something seductively absorbing about such unaccountable organisations which may or may not really exist. Joseph Finder’s excellent novel The Moscow Club (1991) features a CIA-connected version of the same idea, and Mark Burnell’s wonderful Petra Reuter tetralogy has a British equivalent. (We will review a Russia-related book in this series very soon).

Russia in Fiction’s approach is to ask two questions of the books we review — what is the book like? And how does it portray Russia? The first can be quickly answered. Charles Cumming is at the top of his game, and his latest novels step up from what went before in terms of page-turning thriller-writing, memorable characters, and satisfyingly constructed plots.

As for how Russia is portrayed, well, the structure of JUDAS 62 provides two bites at that particular cherry. As well as the fairly common ‘big bad Russia’ take that has re-emerged in Western thrillers over the past decade (see our review of Alex Dryden’s Death in Siberia (2011) for discussion of this re-emergence), there is also the large section of JUDAS 62 that is set in Voronezh in 1993.

The 1993 aspects of Russia in this fiction intrigue from the physical and political perspectives. The standard take on these years —in academic writing, memoirs, journalism, fiction, and indeed from our memories— is one of chaotic state collapse. Russia in Fiction remembers it vividly. For some —more often the young— exhilarating freedom seasoned the hardships of that time; for the older generation, it was an era more likely marked by the bitter taste of certainties and stabilities removed.

In a description that brings to mind that quoted in our review of James Hawes’s Rancid Aluminium, JUDAS 62 draws this temporal setting well as Kite arrives at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport.

Strawson had warned him that the arrivals hall at Sheremetyevo was ‘like the fourth circle of Dante’s Inferno’. Kite thought of this as he emerged from the Customs area to be surrounded by a phalanx of unsanctioned taxi drivers imploring him in broken English to accompany them to the car park and to pay five times the going rate for a journey into Moscow …

His driver was a moustachioed, middle-aged Muscovite with a faded colour photograph of his wife and children tacked to the dashboard. He had been a politics professor, hence his good English, and treated Kite to an unbroken monologue about the contemporary political situation so that he might go home and ‘tell the world about the chaos in Russia’.

JUDAS 62, Chapter 12

That moustachioed former politics professor is uncannily on the nail, as Russia in Fiction remembers precisely such a person —moustache and profession matching— making ends meet in the early 1990s by cooking meals for visiting Westerners in dollar-only city centre apartments.

Other descriptions similarly bring to mind those days.

There was a café open … offering not much more than tea and coffee, some dehydrated pastries and a few open sandwiches which looked as though they’d been on display since the 1991 putsch.

JUDAS 62, Chapter 12

Reading that, I’m back in the city of Kursk in 1993, warning a visiting British dignitary —I’m looking after him in a guide-cum-interpreter fashion— against trying some very tired looking open sandwiches in a similar establishment. He ignored me. Most of his journey on the night train back to Moscow was spent locked in the toilet.

As for Voronezh itself, descriptions are fairly meagre.

He had pictured a bland, medium-sized Russian town.

JUDAS 62, Chapter 13

An anticipation that doesn’t say much for any briefings given to Kite, as Voronezh is a major city of around a million inhabitants. About the same population as Birmingham, if it was in the UK Voronezh would be the second biggest city in the country. (Though Russia’s vast space does not necessitate the distinction between cities and conurbations that muddies such comparisons with the more crowded United Kingdom).

But Kite does at least find himself surprised when

His first morning in the city showed Voronezh to be a much larger, more sophisticated place than he had imagined … his route into work passed along the sweeping banks of the Voronezh River into an old town of wide boulevards and pretty nineteenth-century buildings finished in pale yellow stucco.

JUDAS 62, Chapter 13

The welcome novelty of the Voronezh setting aside, so far, so relatively straightforward. Russia in 1993 is still in shock from the fall of the Soviet Union. Emigration westwards is a common goal. But where Cumming steps out from the standard portrayals is when it comes to Kite’s run-in with the Russian security services, in 1993 known as the FSK. Cumming’s FSK are more organised and resourceful than some accounts of the former KGB in the early 1990s would have them. There is fictional rationale for this, since it is Kite’s leading opponent in the FSK, Mikhail Gromik, who later returns in the contemporary narrative that makes up the second half of JUDAS 62.

When it comes to the contemporary narrative, the Russia-in-fiction element comes not in nuanced setting but in the portrayal of Russia —or more specifically its security services with the support of its state— as a brutal seeker of vengeance on those it deems traitors. The Litvinenko and Skripal cases are used in evidence, but Cumming goes further than that. In particular, JUDAS 62 cites as if established fact one of the, let’s say, less proven accusations against the Russian security services, regarding an explosion in Dagestan that occurred in September 1999 at the time of an incursion by anti-Russian rebels. (There are plot-driven reasons for this, in providing a motivation for the actions of one of the Russian characters.)

Nonetheless, there are elements of nuance in that JUDAS 62 does not just slip into a whiter-than-white portrayal of its off-the-books western security service. For all the vivid description of biological poisoning that the novel lays at the door of the Russian security services, it is the hero of JUDAS 62, Lachlan Kite, who hatches a plot to smuggle caesium-137 from the UK into a third country, and then applies this radioactive isotope to clothing, shoes, the inside of a suitcase, and various points in a hotel room.

On a lighter note, and if you will forgive us ending this review with a standard Russia in Fiction diversion into pedantry, we raised an eyebrow when Lachlan Kite’s right-hand man asserts that Russian operatives are still awarded the Order of Lenin.

’By the time Bellingcat had put the scoop online, the bad guys would have been back in Moscow for a month polishing their Orders of Lenin.’

JUDAS 62, Chapter 3

Three decades after the collapse of Communism. But may be he was joking. After all, it is quite a good line.