With the exception of this one post, the Russia in Fiction book blog has been on hold since February 2022. Writing reviews of stories about Russia has seemed too frivolous whilst the reality of warfare has come to Ukraine and Russia. Just as Trofim found music frivolous when he was immersed in conflict and death (see below). Reading about Russia and Ukraine in the daily news has been enough these long months, leaving little desire left for leisure reading to feature the Russo-centric plots that are grist to Russia in Fiction’s blog mill. We have instead turned to other settings for escapist thrillers and more literary novels alike.

But a novel of war has —temporarily at least— released the blog brake. And in that sense, After Silence seems a fitting title.

Jessica Gregson’s After Silence marks both exception and return. We read it at the end of summer and feel constrained by the relative lack of publicity and reviews concerning this fine book to tell Russia in Fiction’s readers how beautifully written and deftly constructed Gregson’s story is.

The setting of After Silence, in the war-blighted city of Leningrad during the year from August 1941 to August 1942, seems tragically appropriate to these days. Gregson’s tale opens with a mother losing her young children and husband as bombs rain down from the air. As the novel progresses, and Leningrad’s starvation seige sets in, death and pain and illness and grief become commonplace.

And if all that sounds too miserable for words, somehow it is not. After Silence is a novel of beauty and friendship, of love and music.

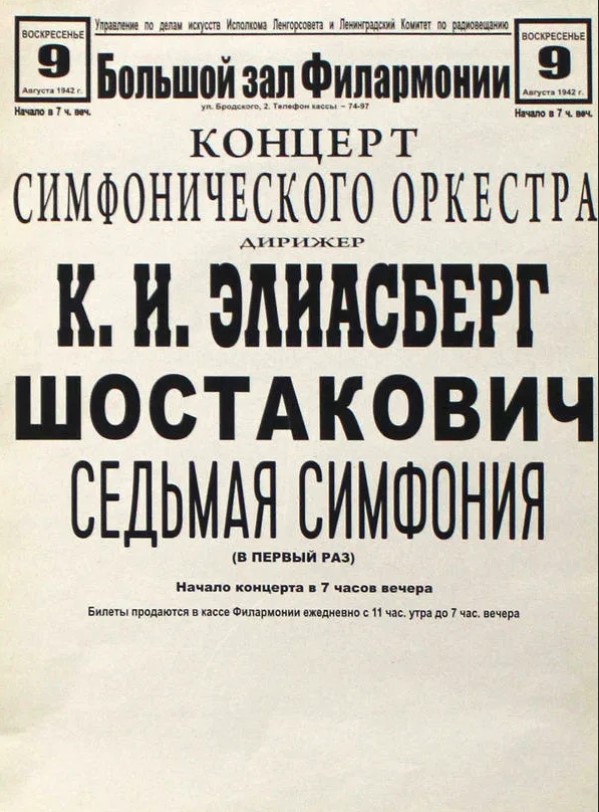

It weaves together the lives of a few musicians as they work towards the defiantly uplifting performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony Number 7, the Leningrad Symphony, in the city from which it takes its name on 9 August 1942.

Within its almost 500 pages, After Silence tells the stories of a handful of individuals whose lives interlock as they rehearse together in the makeshift Leningrad Radio Orchestra, under the baton of Karl Eliasberg, a real life figure who incidentally appears in another recent novel, Ben Creed’s City of Ghosts (2021).

Amongst all the loss and fear, hunger and destruction so well portrayed by Gregson, the characters in After Silence discover too new breaths of life. Enemies become friends, sacrifices are made for strangers, deeper truths are revealed, and glimpses of a new found freedom of spirit emerge.

There is Trofim, the trumpeter, one of several soldiers brought in to supplement an orchestra depleted by the exigencies of war. He travels on the trolley bus from the front line to rehearsals.

These days, he had the idea that there was a Trofim the Soldier, whom he waved off every morning and who waited for him at the Front every day, and there was Trofim the Musician, who was packed away for the evening somewhere in the vaults of the Radio House, to be dusted off for rehearsals.

AFter Silence, Chapter 19, II

Trofim develops a soft spot for Lidiya, who lives in the same apartment block as violinist Katya. For Trofim, playing his trumpet lifts him out of the fear and noise of warfare.

‘The band that I was playing with — they were wiped out, right at the start of the war. I was the only one to survive. And when I was reassigned to the Leningrad Front, I signed back on as a rifleman. The music —’ He hadn’t been able to bear to even listen to it for months — not until the Symphony. ‘It seemed so frivolous.’

After Silence, Chapter 19, I

For Lidiya, the brutal hardships of war sit alongside the different tragedies that she experienced in the pre-war years, when her husband was arrested and disappeared; a victim of Stalinist terror.

‘One of the women I work with … when war was first declared, she was rejoicing. All of a sudden, it was as if all of these things she had been holding back for years were pouring out of her mouth. She would have welcomed the Fascists into the city with open arms, because she couldn’t believe it would be worse than anything she had already lived through. Two of her sons had been in the military, and in 1938 — well, you know what happened as much as anyone’ …

She closed her mouth with a deliberate snap, as if was the only way she could stop herself from talking. For a moment neither of them spoke — in the hush Trofim could feel his heart hammering; this manner of talk tended to bring about an entirely physical panic response in him — and then Lidiya laughed. ‘I suppose if nothing else comes out of this war, at least for a few moments we can say what we think.’

AFter Silence, Chapter 9, I

The notion that the war years, for all their intensity of hardship and grief, provided a time when the controlling brute hand of Stalinism was lifted from the city of Leningrad has been attested to by survivors and historians (as noted in our review of The Betrayal by Helen Dunmore).

Characters such as Trofim and his friend Sasha in combat at the front, or Lidiya and the other residents of the apartment where she lives, portray companionship and true comradeliness. Whilst some characters succumb to despair or reveal their malevolence, it is the strong strand of human goodness in the face of existential hardship that makes After Silence so moving a story. Both during the novel’s present, the siege of Leningrad, and its flashbacks to the preceding decades of civil war, revolution, class warfare, and dictatorial oppression, the kindness of individuals lightens burdened lives.

Front and centre in terms of the plot and characters of After Silence stand Katya, who loses her husband and daughters to a German airforce attack in the novel’s prologue, and Dima, the blind young violinist, with whom she begins to revive feelings of life and love. Their stories intertwine and are made the more solid by a well-paced revealing of their pre-war lives.

To great effect, Jessica Gregson depicts Dima’s experience of blindness, as he grows from child to man.

Removed from his lovingly boisterous rural family home, seemingly abandoned to an austere 1920s school for blind boys, given a release from his emotional pain and anger by a caring teacher who introduces him to music, Dima’s story is movingly told.

Gregson carefully describes, in each situation that Dima finds himself, how it is to be blind and yet thrive. The scene where he wakes up in a strange apartment on a visit to Leningrad stands out.

It was the first time he had woken in an unfamiliar room since his first day of school, and for a moment fear rushed in, the floor seemed to shift, he was abruptly, frighteningly aware that he had no idea how big the room was, whether a wall was inches from his nose or miles away, what myriad obstacles and traps there might be standing between him and the bathroom. Mentally, he shook himself: bravery was all very well at school, where he knew every wall and every step and every person in the place, but if he quailed in the face of the unfamiliar his courage was worthless. The fear receded as quickly as it had come. Dima felt for and found the sense of place and space he had learned to cultivate. Objects arranged themselves around him, their nearness and solidity: the sofa from which he had just risen, something that loomed at knee-height —probably a table.

AFter Silence, Chapter Eleven, II

As Dima’s relationship with Katya develops, he, a relative newcomer to Leningrad, shows her, a lifelong resident, aspects of the city that she had never noticed. One day she is walking her normal route through central Leningrad across the Anichkov Bridge, accompanied by Dima. The landmark statues of rearing horses on each corner of the bridge had been removed by the authorities to protect them during the Nazi bombardment.

Dima must have heard her draw in her breath; he always heard more than Katya expected him to. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing,’ Katya said, her customary, instinctive response, and then: ‘it’s the bridge. The horses. I keep thinking I’m used to them being gone, but sometimes it still catches me unawares .. Oh, of course, you wouldn’t have seen —’

‘I know about the horses, Katya,’ Dima said, chiding. ‘Everyone talks about the horses … Come on. I want to show you something.’ … Dima, hunkered down on his heels by the railings of the bridge, drew some curious looks from passer-by — only a month or two before, you could sit down and die on that bridge without anyone paying much attention … Dima took her hand, drawing her closer —

‘Oh!’ She caught her breath; a feeling ignited that could only be delight. Squatting down beside Dima, she put her hand next to his, on the ironwork wrought into the fabric of the bridge.

‘See, horses,’ Dima said. His voice was mild, but his face was ablaze with smug triumph. Grinning back, unable to help herself, Katya traced the sculpted metal horses that formed part of the railings, face to face, their hooves like flowers.

‘I can’t believe I never noticed’.

AFter Silence, Chapter 11, I

After Silence tells an agonising yet somehow uplifting story. In fact, After Silence tells a set of interlacing stories of lives lived in a time of war. The lives of men and women who had already experienced decades of dislocation and dictatorship before the bombardment and starvation of war arrived.

Jessica Gregson has written a moving novel of hope and love and sacrifice, and has done so within a storyline that moves steadily back and forward, here bringing gasps of surprise, there prompting pause to gather oneself. The reader is taken to Leningrad when war comes, and walked through the hell of that first wartime year accompanied by the ever-louder notes of music that bring a measure of restoration. This review touches on themes and re-tells a few vignettes; but After Silence requires and rewards reading in full.