Russia in Fiction has reviewed nearly a hundred books set in Russia, and read hundreds more. Katherine Arden’s The Bear and the Nightingale is the first novel we have reviewed that is set in Rus’, as opposed to the modern state of Russia. It takes us also into a genre not so far covered here —that of historical fantasy— and from the point of view of the many fans of that genre, this is a high quality entry point.

The Bear and the Nightingale made the shortlist for several awards of the ‘first novel’ and ‘best new writer’ type, and the Winternight trilogy which it launched was also a finalist in the Best Series category of the Hugo Awards, given annually for works of science fiction or fantasy.

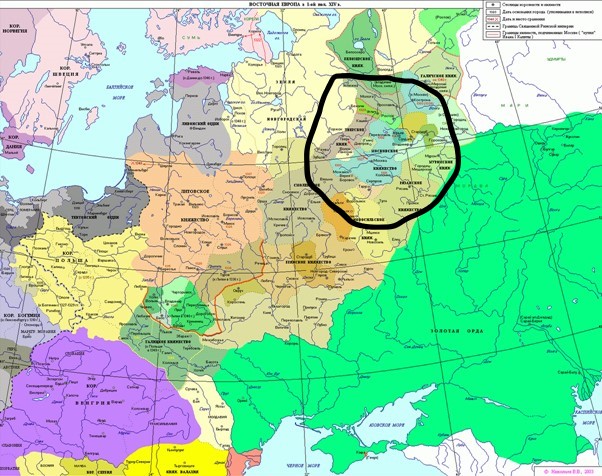

Katherine Arden sets her work in medieval Russia. More specifically, in mid-14th century Muscovy — a time of boyars and peasants, of hierarchy and hardship, of paganism and Russian Orthodoxy.

The tale that Arden weaves centres on Vasya, the young daughter of a provincial boyar whose territory lies on the northern edge of Muscovy. And lest you imagine a rich aristocrat in a grand house, don’t forget that this story is set in the Dark Ages. It begins with the family gathered together in the communal space that made up a peasant dwelling, or izba. Status meant that this house was the centre of the enclosed area, surrounded by forest, from where the family’s territory was overseen. Life was lived around the stove during the harshness of winter, and outdoors in field and wood when weather allowed or necessity demanded.

Vasya is the youngest child. Her mother —the daughter of Ivan I, Grand Duke of Moscow (1288-1341)— had died at her birth and she is being brought up by her noble father, her elder siblings, and the housekeeper, Dunya.

So far, so non-fantastical.

The fantasy element comes in the presence of the spirits of Russian folklore. In The Bear and the Nightingale, these are real characters, existing and exercising their influence; and Vasya has a particular affinity with them. They range from the domovoi household guardian spirit and the vasila protector of stables and livestock, through the less domesticated nature spirits such as the malevolent vodianoy water sprite and bolotnik swamp demon, to the powerful and threatening Medved (bear) spirit that brings death and his brother, Morozko, the winter spirit.

Arden’s novel depicts the unconstrained Morozko of folklore, rather than the somewhat tamer —and, since untainted by religion, Soviet-approved— Father Frost figure of more contemporary children’s films, cartoons, and New Year cards.

The narrative drive and tension of the story stems from the appearance in Vasya’s isolated world of two figures who, like her, perceive the reality of such spirits, but unlike her, see engagement with them as dangerous witchcraft. One such figure is her new stepmother, Anna, and the other is the attractive young Orthodox priest, Konstantin. The devoutly determined alliance of Anna and Konstantin produces an increasingly persistent struggle with Vasya as she approaches adulthood.

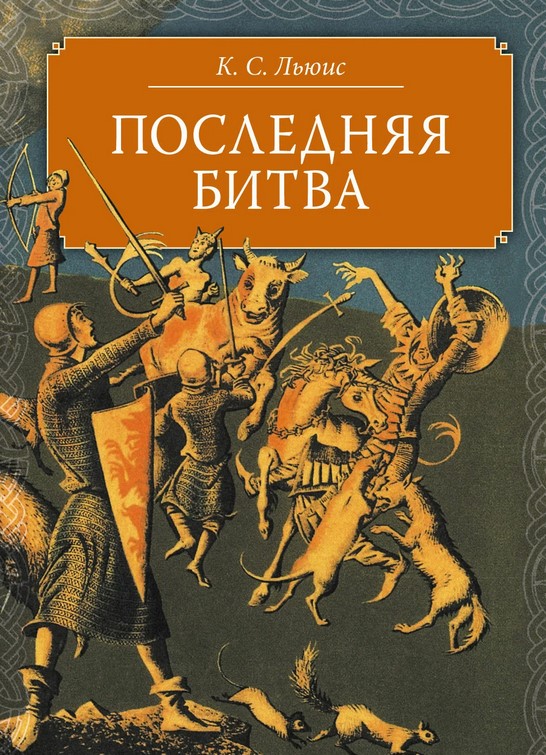

Alongside the relentless Narnia-esque gathering of magical forces that draws The Bear and the Nightingale toward its climactic battle, Katherine Arden depicts too the earthly norms of the novel’s setting, most notably in the visit of Vasya’s father and brothers to the court of Ivan II —or Ivan the Fair— the Grand Duke of Moscow.

The Grand Prince of Moscow was indeed very fair. His hair gleamed like palest honey. Women swarmed around this prince’s golden beauty. He was also a skilled hunter and a master of hounds and horses. His table creaked under a great roast boar, crusted with herbs.

The Bear and the Nightingale, around p. 38

But Vasya’s brother Sasha is less impressed with the riches of the medieval court, than he is with the peace and calling he finds in the presence of the monk, Sergei Radonezhsky. He longs to join him in the monastery.

“It is a hard life we lead here,” the monk went on more seriously. “You would build your own cell, plant your garden, bake your bread, aid your brothers as necessary. But there is peace here, peace beyond anything. I see you have felt it … Yes, yes, many pilgrims come here, and many of them ask to stay. But we only take seekers who do not know what they are looking for.”

“Yes,” Sasha said at last, slowly. “Yes, I would like to stay, very much.”

“Very well,” said Sergei Radonezhsky, and turned back to his baking.

The Bear and the Nightingale, p. 41

The portrayal of Sergei Radonezhsky, his holiness and peacefulness, does not fulfill a great function in terms of the novel’s plot. It is key though to the author’s portrayal of tensions between Russian Orthodoxy and the older pagan and folkloric beliefs of the people of the land of Rus’. With Vasya the undoubted heroine of the story, it would have been easy for the unlikeable machinations of devout stepmother Anna and Orthodox priest Konstantin to stand as representative of an unfeeling religion being imposed from beyond Vasya’s village world.

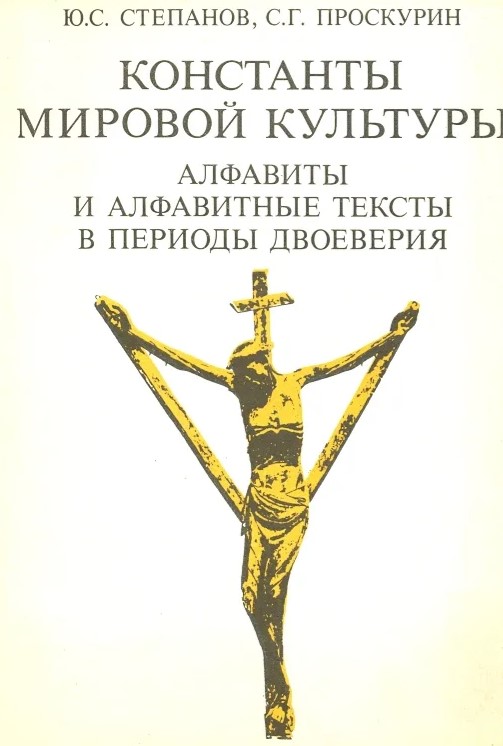

But Katherine Arden, who has lived in Russia and knows its cultural history, provides a more balanced portrayal of the concept of dvoeverie, double-belief or dual faith. She draws good and bad in both Orthodoxy and pagan peasant beliefs, depicting them as intertwined in the worldview of the people.

Whilst dvoeverie refers specifically to the mix of Orthodoxy and pagan beliefs, dvoeverie also brings to mind more contemporary ideas, particularly relating to the ‘cognitive dissonance’ acknowledged in much of the Soviet population in the later decades of the USSR in particular, with a public-facing commitment to Marxism-Leninism co-existing with private scepticism of the same. Though cognitive dissonance is not quite dvoeverie, since in the latter both Orthodoxy and folkloric beliefs are held almost equally.

Fantasy fiction is a major genre, the English-language examples of which rarely engage with Russia. The Bear and the Nightingale represents a fine example of Russia —or more specifically, medieval Muscovy— being brought into the genre, and an uncommon example of the Russia in fiction setting being before Russia even was.