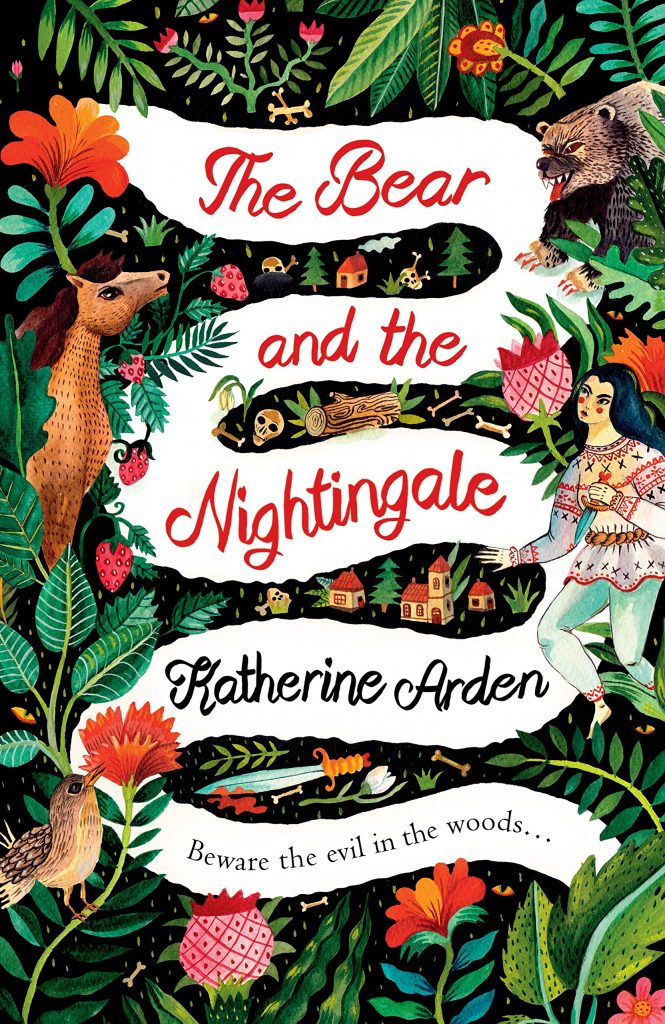

Russia in Fiction has reviewed nearly a hundred books set in Russia, and read hundreds more. Katherine Arden’s The Bear and the Nightingale is the first novel we have reviewed that is set in Rus’, as opposed to the modern state of Russia. It takes us also into a genre not so far covered here —that of historical fantasy— and from the point of view of the many fans of that genre, this is a high quality entry point.

The Bear and the Nightingale made the shortlist for several awards of the ‘first novel’ and ‘best new writer’ type, and the Winternight trilogy which it launched was also a finalist in the Best Series category of the Hugo Awards, given annually for works of science fiction or fantasy.

Katherine Arden sets her work in medieval Russia. More specifically, in mid-14th century Muscovy — a time of boyars and peasants, of hierarchy and hardship, of paganism and Russian Orthodoxy.

Continue reading