Part one of this review is here.

Jason Matthews comes to espionage fiction as a member of the ‘former spy’ school of writers. He is ex-CIA. The backcover blurb on Red Sparrow has veteran US thriller writer Nelson DeMille proclaiming that

Jason Matthews is not making it up; he has lived this life and this story, and it shows on every page.

Nelson De Mille, on Red Sparrow

I’ll go with Nelson DeMille to the extent that Matthews has some revealing insights into the world of espionage, if not of contemporary Russia. There is a good deal of the standard tradecraft familiar to spy thriller readers, and then there’s a little beyond that. I particularly enjoyed the surveillance team made up of pensioners so experienced that they eschewed standard methods as too easily rumbled, and engaged instead in

predictive coverage … situational projections … anticipatory deployments

p. 302

They got a feel for what was going to happen and instead of following the target, they went ahead. I’ve no idea whether this is based on Matthews’ experience or not, but it makes an interesting addition to the manual.

But for all its strengths, from a Russia-in-fiction perspective the real trouble with Red Sparrow, for anyone who knows Russia, is that Jason Matthews’ portrayal of 21st century Russian life does not stack up.

OK — I know it’s fiction, and thriller fiction at that. But when we are talking Russia in fiction, Matthews is writing about Russia, but what he’s describing is the Soviet Union.

To Matthews, nothing has changed in Russia for decades. It is as if the Communist dictatorship still rules, the economy is still stagnant, and the country still stuck in the Brezhnev years.

The Russian authorities and secret service figures in Red Sparrow are almost all brutal, stupid, and uncomprehending. They fear to contradict superiors in case they are killed. They fear that failure in post will see them sent to a prison colony. And when a Russian decides to betray their own country and work for the CIA, they are persuaded to do so by the contrast between such ignorant cruel backwardness, and the relaxed and open goodness of Americans.

But it is not just the politics — after all, politics is arguable and setting up good against bad is part of the thriller writer’s craft. It is the plain wrong stuff that undermines Red Sparrow in terms of Russia in fiction.

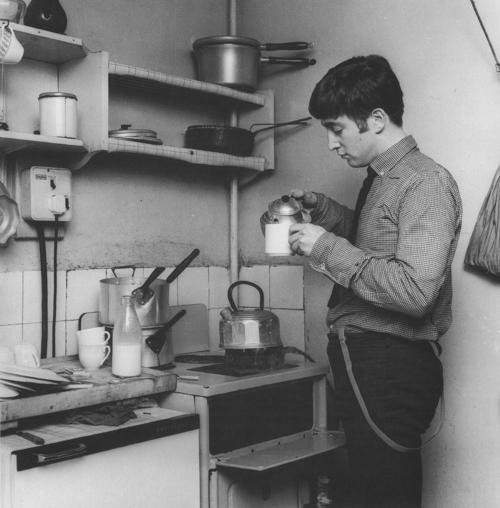

In the world of Red Sparrow, successful Russian intelligence officers live in poorly furnished flats and have little money.

The carpet was threadbare, the wallpaper faded and bubbled with age. A battered teapot on a single-element propane stove was too old to whistle. It was small and dingy, but a Moscow apartment not shared with relatives or work colleagues was still an inexpressible luxury

p. 104

Jason Matthews writes as if describing 1970s Soviet Moscow, or even earlier, rather than today’s thriving metropolis.

In Red Sparrow even the main SVR (Russian foreign intelligence service) office in Helsinki consists of

plain wooden desks, set up in vaguely staggered rows. None of the desks had a terminal, but most had electric typewriters with odd lacquered turqoise covers sitting on small metal typing tables

p. 149

I am not sure why Matthews imagines that the intelligence services of Russia still exist in museum-like caricatures of the pre-internet age.

Rather than summoning up the image of a well-resourced contemporary intelligence service, these descriptions, and the Finnish setting of Red Sparrow, brought back instead memories of a visit to the marvellous Spy Museum in the city of Tampere. (A city known to Russia-watchers as being the location of the first ever meeting between Lenin and Stalin, at a conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, in 1905.)

There is one sentence which encapsulates this strange reluctance to write about modern Russia as it is, rather than re-hash some overblown Brezhnev-era exaggeration.

Dominika is worried about what will happen to her if she fails in her Helsinki mission. She muses about the results of failure, and imagines the consequences, a time when

another agent hears how she was sent to lagerya, the camps, or when the Moscow watchers read in Pravda how she died.

p. 242

There is a double-whammy here. First, the idea that in today’s Russia a failed intelligence operation leads to agents being sent to the camps or executed. Second, the assertion that Pravda (the newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party) is still the paper of record in Russia, several decades after the Soviet Union collapsed.

Jason Matthews inserts Russian phrases all the way through Red Sparrow. So much so that some sentences read a little like a teach yourself Russian book, or as if he is quoting a Russian-English dictionary.

“Do you intend that it should be a plovaya zapadnya, a honey trap?”

“The target is zastenchivyj, timid, shy”

pp. 63-64

Another recurring trait is that each chapter ends with a recipe box, showing how to cook something that the characters have eaten in the preceding chapter. It’s OK, at first, but does get a little distracting as the story hurtles towards its climax. Every chapter has to have food, and the reader (or this one, at least) is distracted from the unfolding plot by the impulse to note what is being eaten, with an eye to the inevitable end-of-chapter recipe box.

From the Russia-in-fiction point of view, it is the factual stuff that grates the most. Red Sparrow is a very readable thriller, but for those who know Russia today, enjoyment may well be laced with a measure of incredulity.

If only Jason Matthews had set Red Sparrow a couple of decades earlier, credibility would have been enhanced.

Still, given how successful Matthews has been in his post-CIA career, I doubt that he would change much now.

And for all the Russia-in-fiction carping over detail, Red Sparrow and the other two novels in the trilogy (Palace of Treason and The Kremlin’s Candidate) are welcome additions to the genre.

Part one of this review is here.