Translated from Dutch by Paul Evans

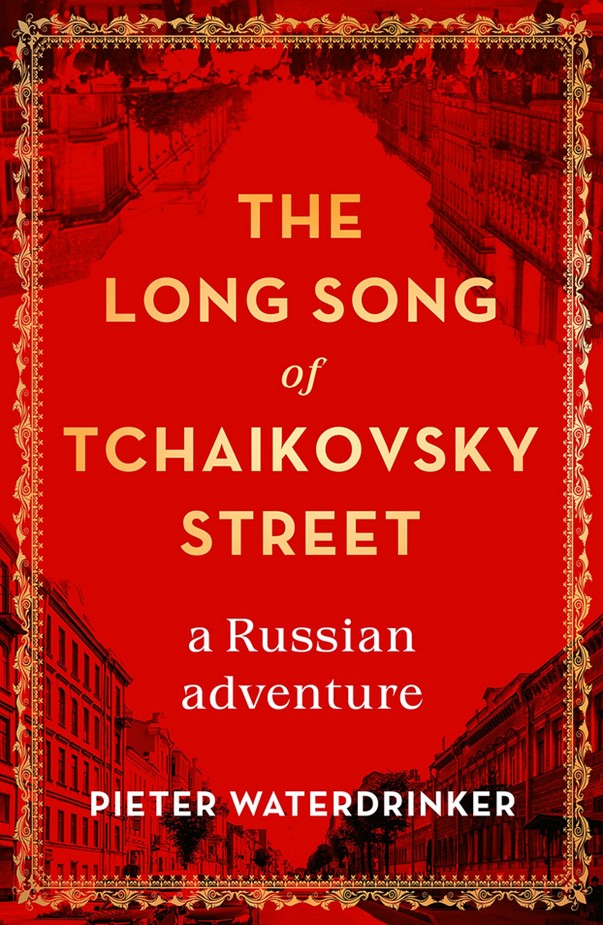

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street is a semi-autobiographical novel by Dutch author, and long-term Russia resident, Pieter Waterdrinker.

Waterdrinker’s take on Russian history —from the revolution of 1917 to its 100th anniversary— puts Russia in Fiction in mind of a knowledgeable boxer, confident in the Russia-writing ring. His experience gives him an assured air; he side-steps the lightweight clichés and name-checking typical of journeymen writers, and slams home his heavy take on Russia’s past, present, and future.

And, particularly from the view-point of 2022, it is an ominously heavy take on what lies at the end of this century-long dance of history.

The dance goes on —yes, the dance always goes on. Maybe this was another false rhyme of history, and we were on the cusp of a new biblical deluge of blood.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 364

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street steps in and out of the decades that define its designated century with a deftness that for the most part declines to take a didactic line straight through from one end to the other. Instead, Waterdrinker hops in and out, bobbing and weaving, taking intertwining routes to set out his and Russia’s narrative.

One such route is the story of the narrator’s own journey, literal and figurative, from the Netherlands to Russia, beginning as an unlikely Bible-smuggler-cum-budding-entrepreneur, and ending up a long-time Russia-resident author and journalist, living with his wife Julia on Tchaikovsky Street in St Petersburg. That the Good Book becomes a tradeable commodity in the murky milieu of Russia’s emerging pseudo-capitalism stands as a metaphor for doomed post-Soviet transition.

Another story strand draws on the research the narrator is doing for a commission he has reluctantly accepted, to write a book for the centenary of the revolution. This enables the narrative of The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street to step in and out of different eras on Russia’s Soviet and post-Soviet history.

And a third story stems from locations, or more specifically, residences: the fellow-inhabitants of the narrator’s Tchaikovsky Street block; the former apartment of Zinaida Gippius, the Russian writer who lived through the 1917 revolution before emigrating to Paris; and the house where Lenin once briefly resided.

Ah, Lenin. Rarely has Russia in Fiction read a book that so thoroughly shafts Vladimir Ilyich. In line with 1917 as the starting point for the book that the narrator is commissioned to produce, Lenin is represented in stark unambiguous terms as the source of Russia’s fall

the Satan whose former residence we’d just passed, the bastard who must have walked here, precisely on this stretch of pavement, where I now advanced with my wife, the cement shovel scraping behind me

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p.133

There is no room for doubting what the authorial voice thinks of Lenin.

The October Revolution of 1917 began with Lenin. The son-of-a-bitch from Simbirsk, who’d given the order to wipe out innocent people like cockroaches, to beat in the brains of the bourgeois scum, to humiliate them and not spare the bullets.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 49

The narrator of The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street takes the view that in 1917 Russia’s future path was not one unalterably set towards the historically unprecedented tragedies that soon unfolded, but that nascent Russian democracy could have succeeded, as it did elsewhere in Europe.

But then, enter Lenin.

… an apostle of death, arriving to destroy. He dreamt of a regime that would carry out a reign of terror … Lenin commenced the death drill, with his shrill voice, his neurotic movements, and his murderer’s eyes,

Here on this balcony was where the victory march of evil began —the forces of darkness, of death. Lenin … continuing to screech, he made his first appeal for total destruction. At that moment, the fate of Russia and many tens of millions was sealed. By one man.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, pp. 111-112, 238

The big story of Russia’s post-revolutionary century set out in The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street is one of tragedy and death, brutality and venality. It is told for the most part through vignettes from the narrator’s own life.

Coming to Russia —as the author of this blog first did— in the late Soviet years, the narrator’s naïvely optimistic initial steps into business involve working alongside a Russian called Pozorski, the original ‘brother in faith of the Dutch believers’ in the Bible smuggling venture, and with a fellow Dutchman called, with undisguised Dickensian nominative determinism, Ragnar Swindleman.

Eventually Pozorski’s trading activities see him shot. A not uncommon fate in the lawless early 1990s as ruthless biznismen fought for control over the riches suddenly available.

A dog deserves a dog’s death,’ Swindleman said … He seems to have been tied up with nuclear material. The greedy fool …!

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 259

Our narrator’s business flourishes, and life seems on the up. Looking to support his impoverished parents back in Holland, and to buy a flat for himself and Julia, he visits Swindleman’s stylish new apartment to give him the details of the bank account into which his share of the profits should be paid.

‘What money?’ Swindleman asked … ‘First, my friend, all of the money is in my account. That is to say, what’s left after buying this flat. Second, you listen carefully to me. I’ll make you an offer to come and work for me. You’ll get a good salary, with back pay, of course. If need be, we can also talk about bonuses, but from now on you’ll NEVER talk about that money again …

You can stand up angrily if you want, but that doesn’t worry me one bit. Keep your hands to yourself, mate! I’ve been at the gym every night for the last few months … Sambo, the Russian martial art! You’ll be sorry for not taking up my offer … Go ahead and sue me! You’ve got no proof – there is no proof … I had our entire correspondence removed from the hotel room this morning … And say hi to that girlfriend of yours! See how long the love lasts now, and do teach me all about these Russian bitches!’

the Long Song of Tchaikovsky STreet, p. 260

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street reveals the wider story of Russia in such small-scale scenes. Swindleman, seizing the company and offering a choice between going along with it or meeting violence, has taken up sambo, the martial art of which Vladimir Putin is an expert practitioner.

Pieter Waterdrinker’s long personal experience of living in Russia across the decades is evident throughout, taking Russia in Fiction back to times and places almost as if we had been there together. Particularly at the end of the Soviet era, when the country was ‘still officially on its way to perfect communism’ but you could buy a bust of Lenin for a few sticks of western chewing gum, and buy theatre tickets at the low state price to sell on to visiting foreign tourist at a huge mark-up.

‘Everyone wanted to go to the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, or the Kirov in Leningrad, to see a performance of Swan Lake, The Nutcracker or Giselle’. (p. 77) (We went to see Giselle at the Bolshoi).

Or the empty state shops supplemented by ‘one person on the street flogging potatoes, carrots and onions from a crate’ (p. 27). Amongst the British students in Voronezh in 1988, these were the three staples from which a whole variety of meals had to be made — mash them, fry them, try them with curry powder; the options were several.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street is a rich book, constructed so as to tell the narrator’s domestic story alongside and within the big story of Russia. The former seasons the latter with affectionate and engaging relationships and the stuff of everyday life. But the overwhelming flavour is more ominous — violence and division, a poverty-stricken population and an imperviously wealthy élite, revolution and war, state collapse and thwarted post-Soviet optimism.

At the headquarters of the KGB, you could walk right through security, simply by putting on an arrogant look, or self-confidently holding up a library card.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 298

Russia in Fiction remembers doing just that card-holding trick to get into the managers’ press conference after the England football team played the Commonwealth of Independent States at the Luzhniki Stadium in 1992.

But for all our smiling at these knowing reminiscences, Russia in Fiction finds the conclusions drawn in The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street to be some of the darkest we have seen in Russia-related fiction. Perhaps appropriately so.

Writing of Russia’s super-rich élite in the second decade of the 21st century, Waterdrinker shows them with their private palaces, their childen in élite western schools, following

the instructions of the satrap who said that they should detest the West, vilify it, hate it. How long could the country continue doing the splits? In the Kremlin, they only had the most modern smartphones, but the messages in their mailboxes came straight from the Soviet Union and from the Middle Ages!

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky STreet, p. 346

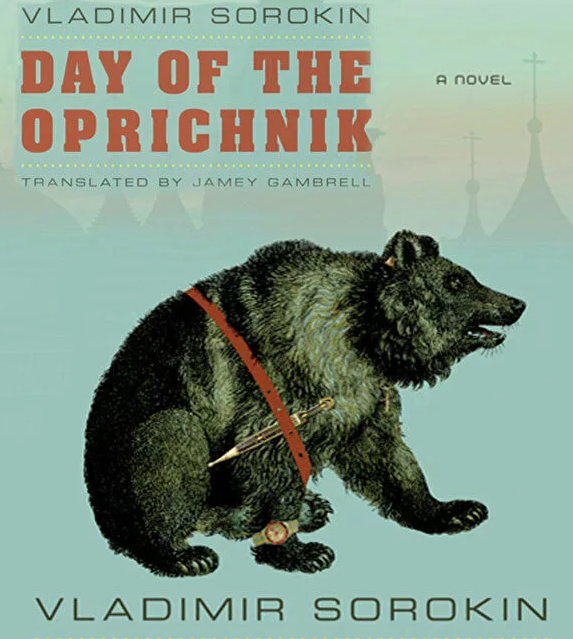

Waterdrinker’s neat line about smart phones and the Middle Ages brings to mind Vladimir Sorokin’s best known novel, Day of the Oprichnik (2006), with its technologically advanced re-instatement of Ivan the Terrible’s brutal and oppressive Oprichnina in the imagined internationally isolated autocratic Russia of 2028.

Memorably and ominously the final chapter of The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street brings the Russian century and the narrator’s life together in a flight of furious fancy and righteous anger, drawing parallels between 1917 and 2017, the oblivious privilege of the global rich and the increasingly poverty stricken masses. Waterdrinker sees a new dread seizing the cocooned élite, whom he portrays as airline passengers floating on silk cushions above the reality of the masses, thinking themselves secure in their privilege and luxury.

But something had gone terribly wrong in recent years … The passengers … looked in astonishment at how black smoke was rising from the earth, from explosions: not the detonation of fireworks, but real bombs.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 361