In its up-coming post, the Russia in Fiction blog will …

Continue reading

With the exception of this one post, the Russia in Fiction book blog has been on hold since February 2022. Writing reviews of stories about Russia has seemed too frivolous whilst the reality of warfare has come to Ukraine and Russia. Just as Trofim found music frivolous when he was immersed in conflict and death (see below). Reading about Russia and Ukraine in the daily news has been enough these long months, leaving little desire left for leisure reading to feature the Russo-centric plots that are grist to Russia in Fiction’s blog mill. We have instead turned to other settings for escapist thrillers and more literary novels alike.

But a novel of war has —temporarily at least— released the blog brake. And in that sense, After Silence seems a fitting title.

Jessica Gregson’s After Silence marks both exception and return. We read it at the end of summer and feel constrained by the relative lack of publicity and reviews concerning this fine book to tell Russia in Fiction’s readers how beautifully written and deftly constructed Gregson’s story is.

Continue reading

Russia in Fiction has a thing about novels published at key junctures in Russian history and set in that same time. (Just search this blog for ‘Chernenko’ to get an insight into how thriller writers saw the Soviet Union in 1984.)

Writing about the Soviet Union in 1991 took matters to a whole new level. In fiction and non-fiction, a good number of authors wrote about the Soviet future only for there to be no Soviet Union by the time their books were published. As a French language summary of The Red Defector put it:

Continue reading

Russia in Fiction has reviewed nearly a hundred books set in Russia, and read hundreds more. Katherine Arden’s The Bear and the Nightingale is the first novel we have reviewed that is set in Rus’, as opposed to the modern state of Russia. It takes us also into a genre not so far covered here —that of historical fantasy— and from the point of view of the many fans of that genre, this is a high quality entry point.

The Bear and the Nightingale made the shortlist for several awards of the ‘first novel’ and ‘best new writer’ type, and the Winternight trilogy which it launched was also a finalist in the Best Series category of the Hugo Awards, given annually for works of science fiction or fantasy.

Katherine Arden sets her work in medieval Russia. More specifically, in mid-14th century Muscovy — a time of boyars and peasants, of hierarchy and hardship, of paganism and Russian Orthodoxy.

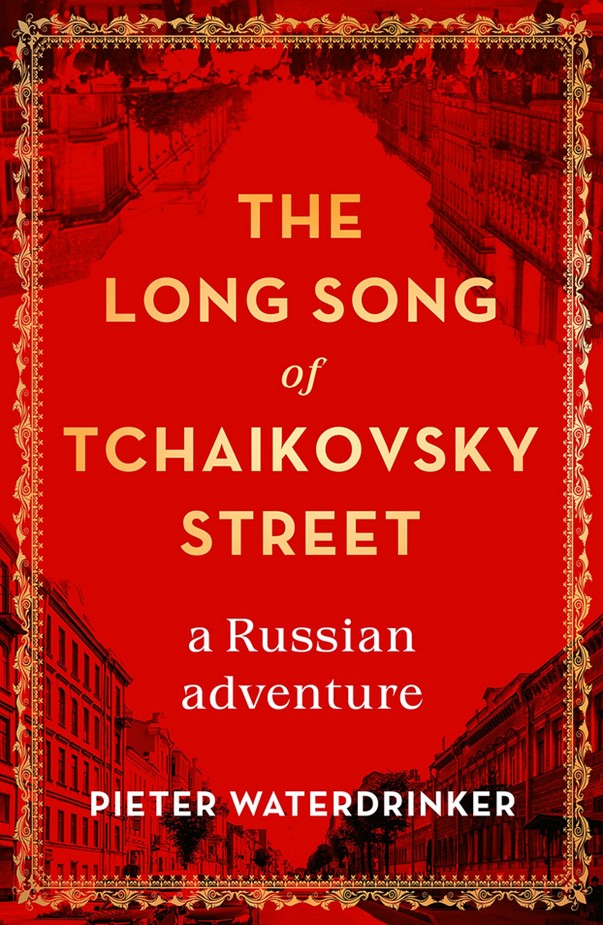

Continue readingTranslated from Dutch by Paul Evans

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street is a semi-autobiographical novel by Dutch author, and long-term Russia resident, Pieter Waterdrinker.

Waterdrinker’s take on Russian history —from the revolution of 1917 to its 100th anniversary— puts Russia in Fiction in mind of a knowledgeable boxer, confident in the Russia-writing ring. His experience gives him an assured air; he side-steps the lightweight clichés and name-checking typical of journeymen writers, and slams home his heavy take on Russia’s past, present, and future.

And, particularly from the view-point of 2022, it is an ominously heavy take on what lies at the end of this century-long dance of history.

Continue readingThe dance goes on —yes, the dance always goes on. Maybe this was another false rhyme of history, and we were on the cusp of a new biblical deluge of blood.

The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street, p. 364

It is a rare thing for a Russia-in-fiction novel to not have Moscow or St Petersburg in it. Yes, there are several that are set elsewhere in Russia, but even these tend to at least visit one or both of Russia’s current and former capitals. Kolymsky Heights is so absolutely determined to avoid them that its central character —sent into Russia by the CIA— enters and leaves by sea from the Far East of the country.

And ‘enters and leaves’ barely covers it. Jonny Porter’s journeys into and out of Russia are perhaps the most convoluted crossings in all the books reviewed on this blog. They take up about a third of this nearly 500-page story.

We will shorten them to a couple of sentences. Porter gets into the Far East of Russia disguised as a Korean seaman, working his passage on a Japanese trading vessel sailing from Nagasaki to Murmansk. He gets out across the ice of the frozen Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska, shot at and shelled by pursuing Russian soldiers.

But before getting too far into the rather fantastical plot of Kolymsky Heights, let’s retreat a little into context.

Continue readingPart one of this review is here

Metro is a semi-autobiographical novel, published in 1985. The author, Alexander Kaletski, and the novel’s first person narrator, share the central facts of their life stories — coming to Moscow from the provinces in the late 1960s to study at a prestigious drama school, beginning a successful acting career in the Soviet Union, including a tour to the West, before falling out with the Soviet regime and managing to emigrate in the mid-1970s.

Just as Aleksander Kaletski and his wife, Elena Bratslavskaya, performed together in the Soviet Union, so too do Sasha and Lena in Metro. The novel follows them as they form a singer-songwriter duo, with a repertoire of self-penned songs that, almost inadvertently, do not fit with the strict Party line required. This of course —combined with their musical ability— makes them an underground hit around Moscow. The trouble is that occasionally they get booked for bigger events and get noticed by those in authority.

Continue reading

Part two of this review is here

Published nearly four decades ago, Metro has long been a Russia in Fiction favourite. We read it back in the 1980s, and at least a couple of times since, latterly re-reading it for this review.

We think of Metro as one of the last English-language novels about Russia written in the pre-Gorbachev era, before the rapid reforms and unravelling of the Soviet state began. Gorbachev came to power in March 1985. Within a couple of years, events sped up, and the certainties of the Brezhnevite era of stagnation were rapidly dropped out the back of history’s peloton.

Continue reading

Russia in Fiction’s previous review was of Tom Clancy and Mark Greaney’s 700-page thriller about Russia invading Ukraine. Given the current war scares, it seemed appropriate.

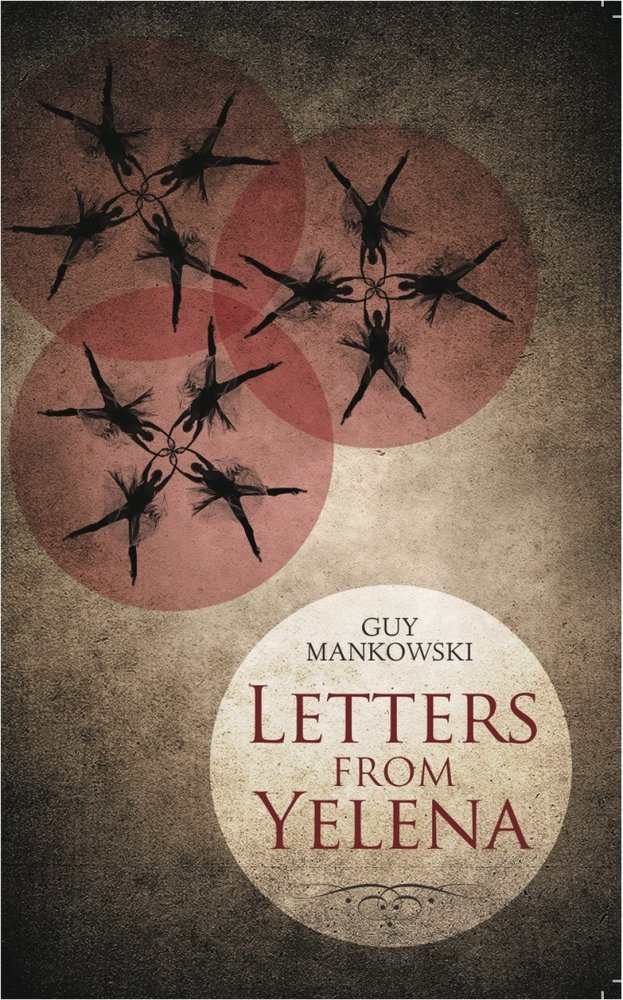

We follow up our review of Command Authority by reviewing a book that in almost every way has nothing in common with a blockbusting Clancy techno-thriller. In almost every way but one in this case, and the commonality is that Letters from Yelena is partly set in Donetsk and in Russia.

Only today President Putin recognised the Donetsk Peoples Republic, in eastern Ukraine, as an independent state. When Guy Mankowski’s Letters from Yelena was published, a decade ago, there was scarcely a hint that this region was on the brink of years of fighting that would lead up to today’s unfolding crisis.

But even if the novel had been written now, we doubt that any of these nationalist, military, geo-political questions would feature much, if at all, in Letters from Yelena. This is no international thriller, but rather a deeply personal and psychological story of one woman’s inner emotional torment. Its structure consists of an interior monologue in the mind of the eponymous heroine.

Continue reading

Russia is about to invade Ukraine. Or so the warnings from the UK, the United States, and various other western governments have been telling us for the past couple of months.

Whilst normal practice would be for analogous war fiction to appear after the event, Russia in Fiction has a fascination with those authors who wrote Russian history before it happened. (See our reviews of, for example, The Fall of the Russian Empire and The Red Fox).

Tom Clancy and Mark Greaney wrote about a Russian invasion of Ukraine back in 2013, before even Crimea had been incorporated into the Russian Federation. Command Authority spotted that possibility in advance. But now, in 2022, the novel’s plot seems potentially prescient once more.

Continue reading