Part one of this review is here

Metro is a semi-autobiographical novel, published in 1985. The author, Alexander Kaletski, and the novel’s first person narrator, share the central facts of their life stories — coming to Moscow from the provinces in the late 1960s to study at a prestigious drama school, beginning a successful acting career in the Soviet Union, including a tour to the West, before falling out with the Soviet regime and managing to emigrate in the mid-1970s.

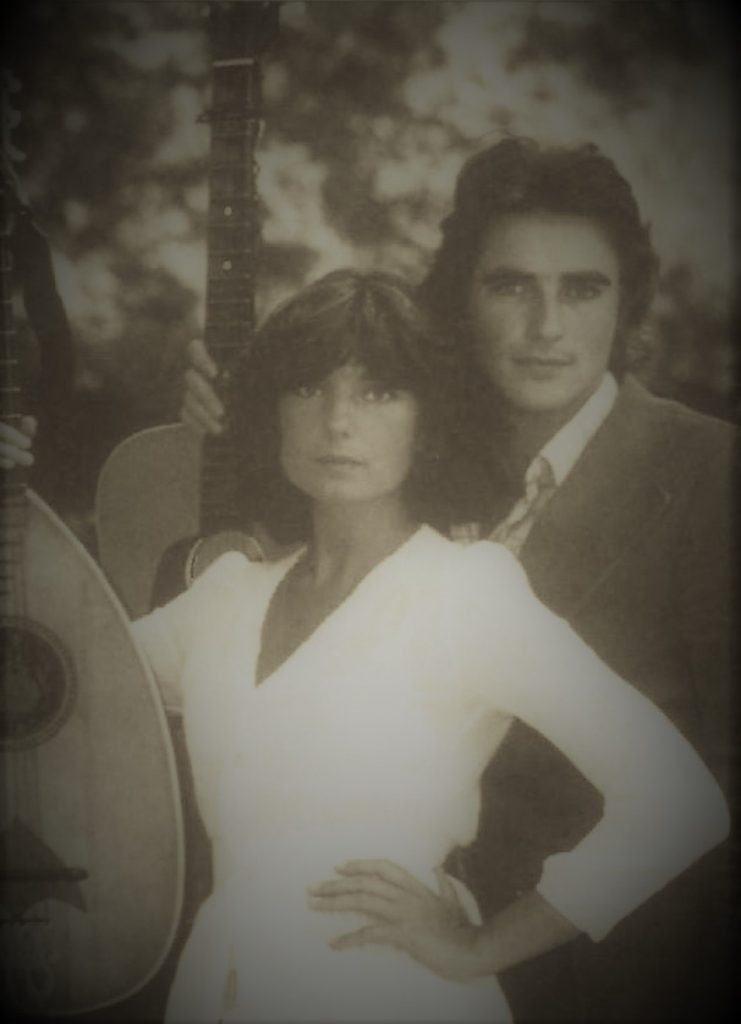

Just as Aleksander Kaletski and his wife, Elena Bratslavskaya, performed together in the Soviet Union, so too do Sasha and Lena in Metro. The novel follows them as they form a singer-songwriter duo, with a repertoire of self-penned songs that, almost inadvertently, do not fit with the strict Party line required. This of course —combined with their musical ability— makes them an underground hit around Moscow. The trouble is that occasionally they get booked for bigger events and get noticed by those in authority.

Kaletski’s writing is at times laugh-out-loud stuff. Sasha and Lena have to sing their songs before a couple of Party men in order to get permission to perform in public.

‘Don’t you have any songs about Lenin?’

‘Unfortunately not,’ I replied.

‘Too bad,’ said the comrades, ‘that’s too bad. Don’t you have any songs about cosmonauts?’ …

‘No,’ Lena said, ‘we don’t have any songs like that.’

‘What a shame,’ they said. ‘Don’t you have any songs about the Comsomols who were crushed to death by Fascist tanks during World War Two?’ …

‘One last question — don’t you have any songs about Soviet holidays like December fifth, May first, or November seventh?’

‘The only one we have is about a holiday of autumn flowers,’ I said. ‘It’s Lena’s music.’

‘What? Lenin’s music?’ both comrades cried … ‘It must be a fine song. It’s just that we had never been informed that Lenin wrote music.’

Metro, pp. 137-139

Metro is full of stories of what happened to its various characters as they try to make a life in Moscow as actors, or indeed as anything that will get them the coveted residence permit that they require to avoid being packed off back to the provinces. There are too many such tales to cover in this review, but taken together they vividly and movingly bring to life whatever the Soviet version of the swinging sixties was in Moscow.

Memorable scenes stand out. Russia in Fiction’s favourite is the affecting account of Sasha and Lena’s ‘wedding’, organised by their friends on the roof-top of an abandoned shack on the Crimean coast.

While Stas placed the silver-plated rings on our fingers, Andrew swung the soup-can censer; and Boris held aluminium-foil crowns over our heads.

… That night, Lena and I slept on the roof of the bathhouse. Our friends had placed candles on its four corners – north, south, east, and west. Wild flowers served as our bedclothes, our blanket – the southern night punctured by stars. The willow’s canopy of branches rustled about our heads, while unseen waves beat against the concrete walls, and our black ship, lit by the four candles, floated along the Black Sea towards the unknown.

Metro, p. 128

And whilst there is a romance to the sofa-surfing, risk-taking, devil-may-care exploits of a close-knit group of friends in Soviet Moscow, the tone darkens as the novel progresses. Kaletksi does not hide the hard realities of life as student days retreat and the central characters try to find their place, and live their true lives, in the stifling, rule-bound world of Brezhnev’s Soviet Union.

Lena is subjected to a sexual assault, by a privileged film director who promises her a movie role. She flees from him but her attempts to tell her family what happened see her incarcerated in a psychiatric clinic, from which a nurse helps her escape before she becomes institutionalised.

‘But I’m not crazy.’

‘You don’t accept reality. To them, that’s schizophrenia …

You’re not healthy if you aren’t happy with your environment. Anybody who doesn’t like the Soviet Regime is sick’

Metro, p. 184

This is the turning point for Lena. In despair she confesses to Sasha.

‘I realized that I hate Soviet films, Soviet theatres, all Soviet art … we can’t even get a job! I’m worn out, tired, cold, frightened. Tired of shuddering at the sight of a policeman, tired of making up reasons for not presenting my passport, tired of worrying about opening the door … Now I’m going to say something terrible; I hate my native land. I know it’s horrible and wrong, but it’s a fact. And once I came to know this, I realized something else — when I was in the ambulance I was screaming about running away because I really wanted to run away, yes, I want to run away!’

‘Where?’ I asked uneasily.

‘Abroad,’ Lena shouted. ‘I want to go away from the Soviet Union .. I simply can’t live in this country any more. I feel as if I’m dying every minute I’m here. I don’t want you to see how I’m dying and I don’t want to see you become an alcoholic, if you’re not one already. We’re different from others – in our looks, in our manners, in our music. They will kill us if we don’t run away. They are killing all the young people who are trying to be free; this is a country of senior citizens. We’ve got to save ourselves. I ask you, I beg you, to promise me that we will go away from here.’

‘I promise,’ I said.

Metro, pp. 185-186

Sasha is allowed to take part in a Soviet theatre group tour to India, Canada, and the United States. He has to leave Lena behind in Moscow; the sort of insurance against defection that was commonly imposed by the Soviet authorities. But Lena tells him that he should nonetheless seize his opportunity.

Almost determined to defect, Sasha bides his time —and stays aware of the touring party’s KGB minders— before slipping away from the group one afternoon in New York. An hour or so on his own in the Big Apple, and he changes his mind, returning in time for his absence not to be noted. But far from curing him of the desire to leave the Soviet Union, Sasha returns to Moscow determined to get out, but next time with Lena. The final chapters of Metro tell the story of how Sasha and Lena achieve their aim. And for those wanting to dig deeper into the real life Kaletski’s successful decades as an artist in the US, there’s a fascinating timeline of press articles online.

Part one of this review is here