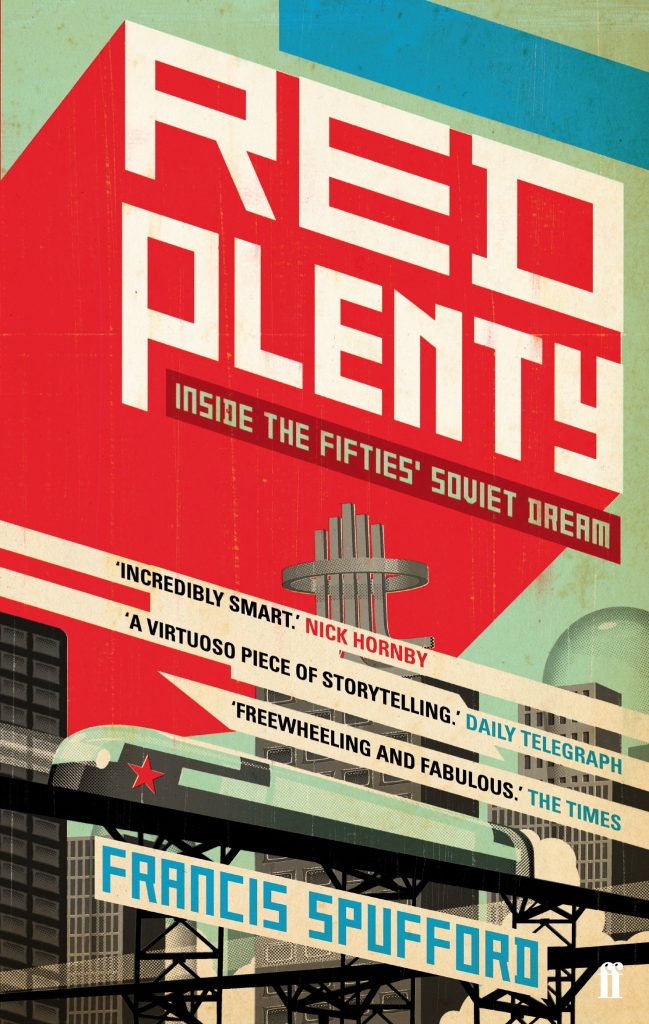

Red Plenty is a beautiful departure from the standard depictions of the Soviet Union in English-language fiction. Francis Spufford’s novel takes the reader not just to Russia in the years of Khrushchevian optimism, but into the heads of a succession of superbly drawn characters who experience those days from their different perspectives.

Front and centre are bright young believers in the Communist idea that rational scientific planning, deployed with intelligence and determined good will, represented a transformative step forward for humankind. We are not talking dull one-dimensional ideologues loaded down with notions of superpower competition, but bright individuals, excited to be alive at that time in a place where the dream of plenty seemed within reach.

once upon a time the story of red plenty had been serious: an attempt to beat capitalism on its own terms, and to make Soviet citizens the richest people in the world. For a short while it even looked —and not just to Nikita Khrushchev— as if the story might be coming true … This book is about that moment.

Red Plenty, p. 5

The bouyant enthusiasm for the Communist dream still to be found in the 1950s shines through Red Plenty. But Spufford’s novel is no fantasy, and within its pages, even before we reach the downslopes of Brezhnevite stagnation, a rich variety of characters embody disparate perspectives — the genius scientists, the career-building Party members, the reformist journalists, the hard-line security forces officers, the criminals, the wheel-greasing fixers, and the singular, powerful-then-deposed leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev himself.

Alongside Khrushchev, a number of Red Plenty’s dramatis personae are real historical figures, whilst most are fictional. Amongst the former are the economist and mathematician Leonid Vitalevich Kantorovich (1912-1986), and the dramatist and lyricist Sasha Arkadyevich Galich (1918-1977).

Red Plenty is an episodic work in six parts and 18 chapters stretching across three decades.

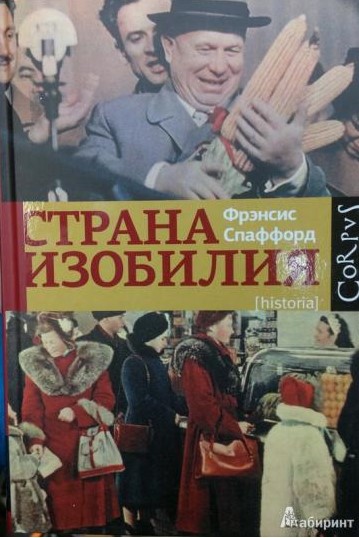

Each chapter is a time capsule covering a particular aspect of the great and dashed hope for —to back-translate the title of Red Plenty’s Russian language edition— a country of plenty.

Spufford’s descriptive abilities and skilful characterisation combine not just with knowledge of Soviet history, but with empathy for those who built their lives in such extraordinary times.

Red Plenty has no plot as such; its overarching narrative is the eventual failure of Communist belief in and boasts of the superiority of a system based on scientific certainties rather than on what it portrayed as the inegalitarian vagaries of the market. There is almost a rueful air to the novel as a whole, an ‘if-only’, not for that particular authoritarian form of government, but for the idea of progress planning away poverty.

A review of this length cannot hope to cover every capsular chapter. Though at the same time it seems invidious to select from amongst them, as each memorably draws back the curtain on a scene from the life of a particular individual. There is a narrative momentum within each, and then, for the most part, we move on. Occasionally a chapter’s central character appears later in the novel, often off to the side of another’s scene.

Each of Red Plenty’s six parts begins with a short historical essay; a necessary scene-setter, as far from all readers can be assumed to know the broad strokes of Soviet history that illuminate Spufford’s expertly crafted microcosmic miniatures. And the novel itself has a wealth of fascinating endnotes —53 pages, to be precise— embedding its elements in the vast amount of historical research done by its author. There are a dozen pages of bibliography too; all English-language sources though, as Spufford does not appear to have Russian.

Little wonder then that some have thought Red Plenty a history book, rather than a novel. And indeed to confuse the issue further, the first five words of Part One of Red Plenty are

This is not a novel.

Red Plenty, p. 3

Far be it from Russia in Fiction to argue with the author himself, but we reckon Red Plenty is a novel. It is a work of fiction, albeit allowing a form akin to an academic work in places. In the same introduction to Part One that proclaims Red Plenty to not be a novel, Spufford is at pains to insist that the book is set in

story Russia, not real Russia … it is not a history. It is not a novel. It is itself a fairytale.

Red Plenty, pp. 3-5

So if we cannot cover all 18 chapters, we can at least note those that have particularly stayed in Russia in Fiction’s memory when thinking back to our reading of Red Plenty.

There are two chapters that stand out because of the historical event in which they are situated. Part One, Chapter Three, ‘Little Plastic Beakers, 1959’ takes us to the American Exhibition in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, for an adroitly drawn account of conversations between selected Russian youths and their American counterparts, as they negotiate the tensions around comparing political systems and trying to engage person-to-person; alternative routes to plenty, exemplified by consumer goods and fashion.

In contrast, Part Three, Chapter Two, ‘The Price of Meat, 1962’ presents a fictionalised version of the infamous Novocherkassk massacre, when workers protesting at economic hardship were shot by Soviet security forces in an event so shocking that not even the regime’s control of information could keep it secret. Though they tried very hard, and it was not until the Soviet Union disappeared that it was officially acknowledged, a memorial was constructed, and President Putin visited to lay flowers and pay respects.

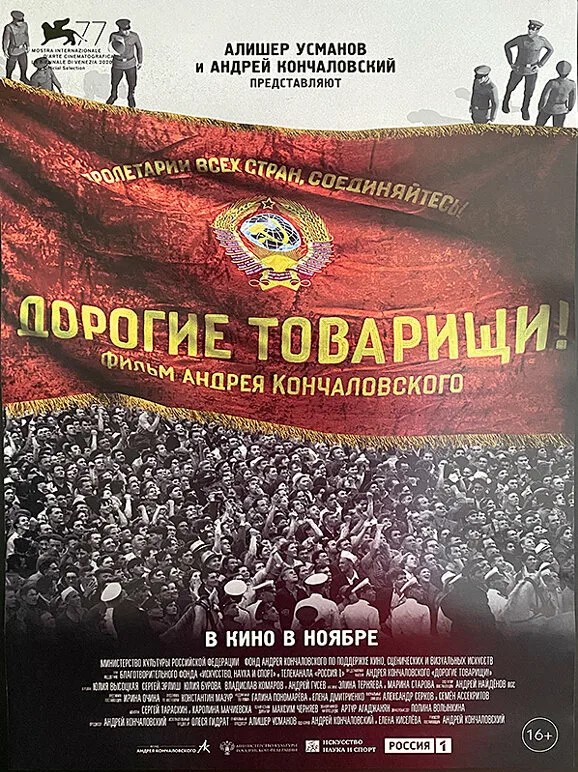

In 2020, Andrei Konchalovsky’s film ‘Dear Comrades’ (‘Дорогие товарищи!) received wide-spread international acclaim for its portrayal of the massacre.

Other chapters stay in the mind because of the characters depicted. Part Four, Chapter Three, ‘Favours, 1964’, centres on Chekushin, a fixer, a black-marketeer, a man who makes his living by connecting people and goods.

He pieced together all stories, if he could. It was his job to do so, he made his living snapping up these trifles.

REd Plenty, p. 234

The Soviet approach to plenty differed from the American one in many aspects, but at the level of the individual the relevance of money represented a major differential. Spufford portrays expertly the comparatively marginal role played by money in the Soviet Union. What was the use of money if there was no access to the goods that might be bought?

[Chekushin] sucked a peppermint as he checked the other item inside [the briefcase], a good fat bankroll secured by rubber bands, with a brown hundred on the outside. He was not, himself, a great believer in money. You could hardly get anything important with it, by itself.

Red Plenty, p, 246

Russia in Fiction’s favourite is Part Three, Chapter One, ‘Midsummer Night, 1962’, as Zoya Vaynshteyn, a biologist, arrives in Akademgorodok, a newly built science university town outside Novosibirsk. Here the state’s resources can be poured into the scientific route to a future of plenty. But if that sounds dull material for a novel, then Spufford’s gift is to personalise it.

Zoya joins the scientific community on a bright sunlit day, a day for parties. She stands out amongst the resident scientists because she is female and good looking. A couple of gawkily awkward male students try to chat up Zoya

‘I’m sure this works brilliantly on eighteen-year-olds’, she said, ‘but I am in fact a thirty-one-year-old. A thirty-one-year-old fruit-fly biologist, exhausted by plane travel and bureaucrats. Got any lines that work on one of those?’

REd Plenty, p. 157

It being midsummer, she and her new comrades go to a party, where young and old, distinguished and less distinguished, gather and talk more openly than Zoya is used to.

‘You all talk so much,’ she said … ‘As if it’s going out of style. I’ve heard things said tonight in public that I thought were strictly whispers for the kitchen’.

Red Plenty, p. 183

At the end of a memorable night, Zoya goes skinny dipping with a newly made student acquaintance. All is perfect and exciting and bright.

Zoya returns again in Part Six, Chapter Two, ‘Police in the Forest, 1968’. By then the brightness of Khrushchevian optimism has been replaced by Brezhnev’s authoritarian caution, and the return of Stalin-lite control. Zoya is ostracised, not the least because of her Jewishness, and is denounced by the Party.

‘The workers of Novosibirsk’, said the rep from the labour union, ‘do not resent the hard-working scientists of Akademgorodok, who are preparing a better life for all by their heroic efforts … but the workers demand that the traitor Vaynshteyn, who is not fit to be called a scientist, should be expelled and face the full rigour of the law for her criminal anti-Soviet activity’

REd Plenty, p. 353

The dream of red plenty has gone forever. But there again, as Francis Spufford told us from the start, it only took place in story Russia, not in real Russia.