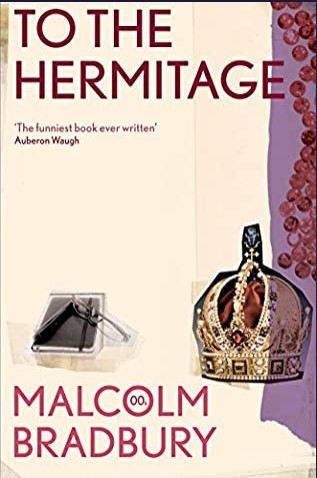

To the Hermitage tells parallel tales of men who travelled to St Petersburg. Both are fictionalised versions of actual journeys.

One being that of Denis Diderot, the French philosopher, who visited his patron, and Empress of Russia, Catherine the Great, in 1773.

The other being the anonymous narrator of To the Hermitage, a version of Bradbury himself —English academic and author— making his way to St Petersburg as a member of a distinguished study group, the Diderot Project, in October 1993.

The very temporal settings speak of the novel’s parallelism.

Russia then as now was in trouble, tugged as it ever has been between east and west.

To the Hermitage, chapter 21

Sir Malcolm Bradbury died 21 years ago this month. In the year 2000. The year that To the Hermitage was published. The year that Bradbury was knighted.

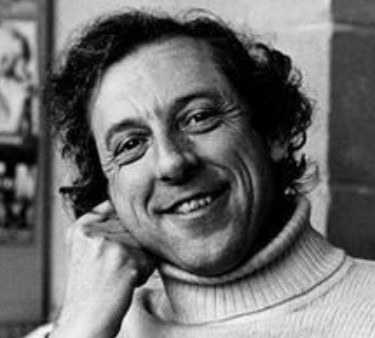

Bradbury (1932-2000) was one of those English cultural figures familiar from the post-war generation. All the best pictures in black and white, often from the 1970s, all leather jackets, sideburns, big ties, long-ish hair, smoking, state school boys, not Oxbridge, not establishment. Think John Thaw, Tom Courtenay, Alan Bennett. A decade or so after the ‘angry young men’ of the 1950s; a decade or so before Thatcherism.

Think too of one of Russia in Fiction’s favourite writers, David Lodge. About whom we note for now just two things — Lodge has not written about Russia in his fiction and so gets no place in this blog; and Lodge’s body of work is thematically and to some extent stylistically similar to that of his great friend, Malcolm Bradbury.

Whether trend-setter, or merely on trend, Bradbury —like Lodge— for most of his career wrote novels about academic life and the socio-sexual mores of the class-riven and slowly emergent permissive society of provincial Britain.

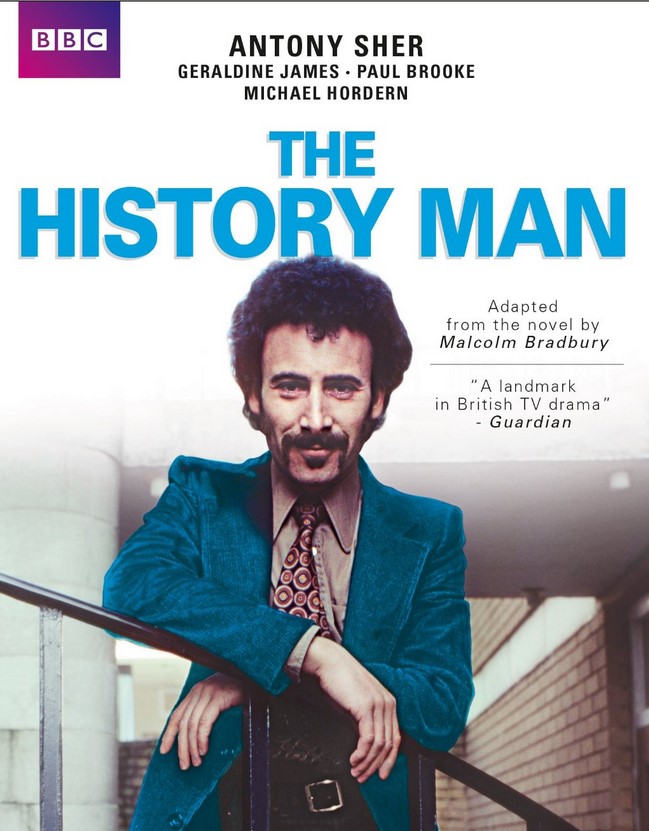

Bradbury’s best known novel, The History Man (1975), was dramatised in a BBC TV series of some renown in 1980.

To the Hermitage was a notable departure from what had gone before, in that at least half of it is historical rather than contemporary in its setting.

Around the same time, Lodge was writing his first historical novel, Author, Author (2004), based on the life of Henry James (1843-1916).

And whilst we are making connections and comparisons, Russia in Fiction will not neglect to link to our preceding review, of Red Plenty (2010) by Francis Spufford. There we discussed the definitional line between history and novel, and Spufford’s opening assertion that ‘This is not a novel’, which he later expands on to explain that it is set in ‘story Russia, not real Russia … it is not a history. It is not a novel. It is itself a fairytale’.

Bradbury’s preface to To the Hermitage similarly begins

This is (I suppose) a story. It draws a great deal on history; but as history is the lies the present tells in order to make sense of the past I have improved it where necessary.

And the preface ends with similar distancing to that deployed by Spufford

And that explains how I came to write this … well, shall we call it a story?

Stylistically To the Hermitage is made up throughout of temporally alternating chapters, headed ‘then’ and ‘now’, and recording the travels to and St Petersburg-based experiences of, respectively, Denis Diderot and the author. As might be expected from an author of Bradbury’s ability, the parallels are carefully incorporated. And they can very much be seen in a Russia-in-fiction light.

Diderot, the great encyclopaedist, was one of the enlightenment philosophers whom Catherine the Great (1729-1796) read and admired in the early years of her reign.

The Empress paid him a huge sum for his library, and Diderot was prevailed upon to travel to the court of Catherine the Great in St Petersburg.

The ‘then’ chapters of To the Hermitage are built around this journey and —in dialogue form— the daily meetings between Diderot and Russia’s ruler; Diderot seeking to present to Catherine a pathway to building an enlightened Russia of emancipated serfs and unheard of freedoms; Catherine in her turn countering

‘Yes, my dear dreamer. You know, there is just one difference between us. You’re a philosopher, and work on paper, which is supple, obedient, does just what it’s told. Where I, a poor empress, must work on human skin.’

To the Hermitage, Chapter 32

Although Bradbury does not explicitly make the connection, one cannot help but think of what would befall Russia a century and a half later, when its rulers would seek to enact the thoughts of a progressive Western philosopher by the name of Karl Marx, only for the Russian people to find that ideas on paper have quite a different force when in practice pressed on human skin.

In their last meeting, Diderot protests to Catherine

‘if you’d followed me, you would surely have created a great society, and made your nation the envy of all humankind’

To which the Empress responds

‘Yes, and if I had listened to you thoughtlessly, every single institution in my empire would have been upturned. Monarchy, law, the church, the budget. The nation would have disintegrated, the borders would have collapsed’

To the Hermitage, Chapter 32

Here the parallels of the ‘then’ chapters with the ‘now’ chapters are a little more apparent. The author’s journey to St Petersburg, along with others involved in the Diderot Project, is undertaken on a Baltic ferry, from Stockholm via Helsinki, in October 1993. It is played out alongside daily reports on the collapsing Russian state, as President Yeltsin —‘Tzar Boris’ (Chapter 7)— is embroiled in an armed struggle with supporters of the Russian parliament.

After decades of a Communist state attempting to enact Marxism, now it was almost literally the case that every single institution in the empire had been upturned, the ruling Communist Party was no more, lawlessness was the norm, the dominant ideology had been discredited, the country was bankrupt, the Soviet Union had disintegrated, and the borders had collapsed.

***************

To the Hermitage is replete with descriptive gems, clever allusions, and philosophical nuance. Whilst dealing with grand themes, Bradbury has also, as ever, produced a richly comic novel.

Russophiles will find much to entrance, particularly relating to 18th century St Petersburg; the years when the Bronze Horseman statue of Peter the Great was raised onto the biggest monolith ever moved by humankind.

The Hermitage of the title features, appropriately, in both the ‘then’ and ‘now’, as —respectively— royal palace and great art gallery. Though the ‘now’ being the early 1990s, the greatness of the Hermitage’s collection is diminishing piece by surreptitiously removed and sold off piece.

And for all the Russophilic richness of To the Hermitage, some of the most memorable scenes and descriptions are of the social mores and mannerisms of Sweden and Finland. (We have to confess that To the Hermitage caused Russia in Fiction’s pandemic-boosted wanderlust to focus on a yearning to return to Helsinki just as much, perhaps even more, than to once again walk along the Nevsky Prospekt.)

A review of this length cannot hope to capture all the literary devices and skilful surprises that a novelist of Malcolm Bradbury’s ability includes in what was perhaps his magnum opus. It is a shame that To the Hermitage is so little known, and too rarely discussed even in overviews of Bradbury’s life and works. Wikipedia’s Bradbury entry merely includes To the Hermitage on its listing of his publications, but says no more about it. (No doubt Denis Diderot’s encylopaedia would have been more diligent). The Guardian’s obituary of Bradbury likewise merely mentions To the Hermitage once in passing; which is one more time than does his obituary in The Telegraph.

We can speculate as to the reason behind this relative neglect. Perhaps the novel’s departure from Bradbury’s habitual settings and style saw him losing his usual audience? Perhaps the publication of To the Hermitage was overshadowed by the author’s death in the same year?

Whatever the case, Russia in Fiction is glad to celebrate To the Hermitage as a work of erudition and entertainment that pulls off the rare feat of portraying in its fiction two Russias, two centuries apart.