Part two of this review is here

Mutilated bodies found in the snow. That is a fairly standard starting point for a Russia-in-fiction detective novel. Think, of course, of the classic of the genre, Martin Cruz Smith’s Gorky Park (1981). Or more recently, G.D. Abson’s second Natalya Ivanova novel, Black Wolf (2019).

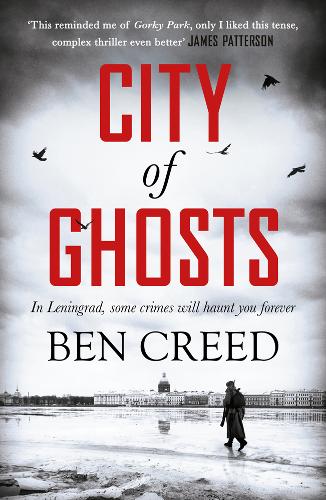

City of Ghosts starts with five mutilated bodies found in the snow. This novel is no shy newcomer sneaking into the back of the Russia-in-fiction incident room hoping not to draw attention to itself.

City of Ghosts is the first of the Revol Rossel thriller series. Set in Leningrad in 1951, as the Stalin era is coming to an end, this is a book that knows its Russia, knows Leningrad, and knows Soviet history. The Stalin era did not limp off the global stage but —so far as its reputation for terror and oppression went— it stayed right on until the end of its road. And Leningrad was a particular target for Stalin’s personal ire.

Within this setting, Ben Creed (the pen-name of the co-writing duo Barney Thompson and Christopher Rickaby) develops a macabre tale brimming over with multiple ideas and intentions.

Continue reading