Russian Hide and Seek (1980) is set in the year 2035 and imagines an England that had been forcibly occupied by the Soviet Union since the mid-1980s. Amis’s fantastical future is of course shaped by the world he knew in the late 1970s.

For all its title, Russian Hide and Seek is a novel about England far more than it is a novel about Russia.

Whereas Donald James —writing The Fall of the Russian Empire (1982) around the same time as Russian Hide and Seek came out— focused with notable accuracy on likely developments in Russia’s near-future, Amis has little to say about Russia and a little more to say obliquely about the declining state of the United Kingdom.

Amis’s scenario building can be viewed as part of a trend in the Cold War years for fiction about an England where the increasing influence of socialism would lead to civil strife and either a potential left-wing (Soviet), or right-wing (Establishment, US) takeover.

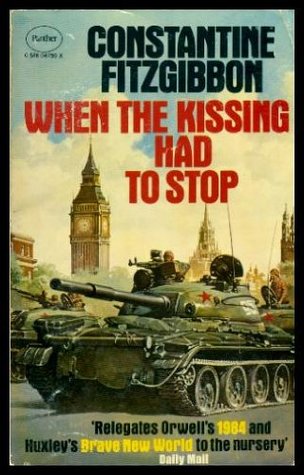

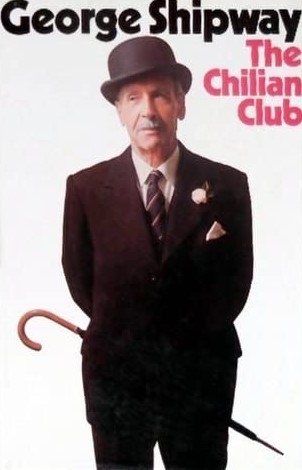

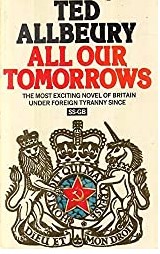

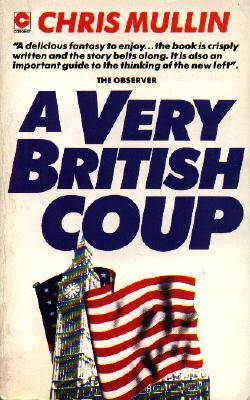

We are thinking of novels such as Constantine Fitzgibbon’s When the Kissing Had To Stop (1960), George Shipway’s The Chilian Club (1971), Ted Allbeury’s All Our Tomorrows (1982), and Chris Mullin’s A Very British Coup (1982). To this extent, Russian Hide and Seek has more in common with Donald James’s debut novel A Spy At Evening (1977) than it does with The Fall of the Russian Empire.

Where Russian Hide and Seek stands apart in the predictive sense though is in its temporal distance between publication date and setting. Russian Hide and Seek is not set in the near future, but a generation or so down the line —in 2035— when remembrance of a free and democratic England has been all but obliterated by Russian rule. It is not at all an account of the Soviet takeover; rather it imagines what would become of an England occupied for 50 years by Russia.

Indeed, Amis only gradually, and in almost throw-away asides, reveals his story’s setting in time, place, and circumstance.

Russian Hide and Seek begins with what appears to be a readily recognisable English scene, pastoral and bucolic, that is made incongruous both by the occasional detail indicating that all is not as ancient and timeless as it appears and then by the simple provision of characters’ names.

A young man on horseback rides home through the countryside. He passes a flock of sheep clustered by an oak tree. He progresses through a small churchyard by a path that runs among ancient gravestones and through a low gateway of brick and stone. Then he arrives home at a grand eighteenth century style house with extensive gardens trimmed by shrubs and hedges, ornamental steps leading up to a stone summerhouse, and a large pond. He hurries up the steps into the house, where he shouts for a servant to come and stable his horse. A white-haired man in a brown frock-coat , with ‘a pink kerchief’ round his neck appears and greets him formally — ‘Good evening, your honour’.

Our hero is clearly wealthy and privileged. He addresses his mother as ‘mummy’, and behaves like the ‘superfluous man’ famed in 19th century Russian literature.

‘Life’s so boring. No wonder I day-dream’ (p. 11)

On one level then, the opening of Russian Hide and Seek is akin to a 19th century rural idyll, Hardy-esque in its English setting, with notes of Turgenev in regard to superfluity.

Except incongruities usurp the familiar. The oak tree is ‘infant’, and in fact none of the oak and ash trees around the house are ‘much more than twenty years old’. The pond is ‘artificial’.

The young man in question, Alexander, is running late for a dinner to which guests have been invited. And who are these guests?

‘The Tabidzes are to be here … Director Vanag is in Moscow .. Deputy Director Korotchenko is bringing Mrs Korotchenko with him.’

Russian Hide and Seek, pp. 11 and 13

But of course, the reader knows the novel’s title and has presumably read enough of the publisher’s blurb or reviewers’ accounts to know that this is not a pastoral novel set in the 19th century. Kingsley Amis reveals the salient features of his setting at the pace required by his plot.

By Chapter Three, Alexander is being invited to the house of Mrs Korotchenko.

‘It’s called The Old Parsonage and it’s about two miles out of the centre of Northampton just off the road to Wellingborough. Most of the English know it by now, we have plenty of official visitors. Ask for the Russian policeman if they don’t understand you’.

Russian Hide and Seek, p. 30

In Chapter Four, Alexander and his father are discussing with a visiting Commissioner, the ‘New Cultural Policy for England’.

‘As far back as the first decade of the century it was beginning to be felt, in Moscow and in London, that the denationing programme, though instituted for good and sufficient reasons at the time, was becoming unnecessary, even retrogressive … the forestry and rural engineering people, I’m told, have their eyes on 2100 for the complete restoration of the English countryside, and between ourselves I take that as about the target date for English culture too, though officially it’s 2060’

Russian Hide and Seek, p. 48

In this manner, Russian Hide and Seek sets out an England under Russian/Soviet occupation. Reference is made to a period known as ‘the Pacification’, and the brutality and destruction of that time are hinted at in the need to rebuild roads and towns, and in the wary acknowledgement by the English that the Russians are in charge. Whilst relations between English and Russian are usually cordial —even friendly-to-amorous amongst the younger generation— threats of violence should the English not fall in line with Russian wishes are ever present, and inter-marriage is illegal.

Two middle-aged men lurched out, talking loudly, drunk at half-past-six. When they saw the Russian uniform they quietened down and straightened themselves, and one of them hastily shut the door, an unnecessary switch to decorum, for the days were past when a member of the units of supervision would have been likely to correct English misbehaviour with riding-whip or pistol-butt. These two must have learned their lesson thoroughly in youth.

Russian Hide and Seek, p. 116

Only in Russian Hide and Seek’s conclusion are a few fleeting details of how England came to be under Russian occupation offered.

‘There had been disorders here, runaway inflation, mass unemployment, strikes, strike-breaking, rioting, then much fiercer rioting when a leftist faction seized power. It was our country’s chance to take what she had always wanted most, more than Germany, far more than the Balkans, more even than America. And she took it, after serious difficulty at first’

Russian Hide and Seek, p. 241

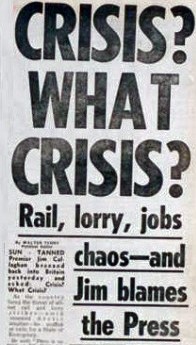

Here then is the moral of Kingsley Amis’s tale — Russian Hide and Seek is a satire on what many, particularly of Amis’s political persuasion, saw as the decline of England.

When Amis wrote the novel, Britain was experiencing the Winter of Discontent, 1979-1980. Runaway inflation had been a feature of the mid-1970s, mass unemployment was increasing still further in 1980, and the reference to ‘rioting, then much fiercer rioting’ was notably prophetic as such a phenomenon broke out across England’s major cities in 1981.

Amis’s fantastical forecast has, however, layers of sophistication. The Russia that is occupying England in 2035 is no longer a Marxist Soviet state. As one of the Russian occupiers says to another over a glass of wine at an evening reception

‘Where shall we date its death? … The year 2000? 2020? – before that, surely. It doesn’t affect the point: as an active force, as something to be reckoned with, Marxism has ceased to exist. Its followers have died or fallen into cynicism or impotence. And what has replaced it? … What has replaced it is nothing, nothingness. No theory of social democracy, or liberalism, anything like that, nor even a non-political code of decency or compassion … So we act; we choose a part not too incongruous with our age and stations and play it out to the best of our ability and energy … I mean the fact of being Russian as an aid to play-acting. The essence of the Russian character, in fact as well as in fiction, has always been theatricality’.

Russian Hide and Seek, pp. 104-105

Amis aims at a broader and deeper target than the ideological and systemic competition between communism and capitalism. His passing notion that by the 21st century Russia will have moved on from cynicism about Marxism to its complete rejection is a faint echo of the front-and-centre idea in Russian Hide and Seek, namely, that when the Russian occupiers make an attempt to restore English culture in England, it will fail because that culture was insufficiently deep-rooted.

The plot of Russian Hide and Seek sees Alexander and some fellow plotters planning a coup attempt, within the official campaign to restore English culture, that will see rule of England restored to the English themselves. A coup attempt? Sounds a bit thriller-like. Believe us, Russia in Fiction has read a lot of thrillers and this is not one.

But of more interest than this plot device is the commentary on what English culture is, and how alien its ancient staples —Shakespeare and the Book of Common Prayer— seem to the English after only a generation or so of separation from them.

It is not hard to read Russian Hide and Seek as a commentary on England at the dawn of the Thatcher years.

Fascinating in its way, but not really the stuff that the Russia in Fiction blog focuses on.