Ralph Peters is a distinctive author when it comes to military novels written in English around the end of the Cold War era; he writes whole novels with Soviet characters only. As noted in our review of his stand-out Red Army (1989), Peters tends to focus in on a small range of characters, rather than panning out to the geopolitical level of strategy and national leadership.

Flames of Heaven is set in 1990 and depicts the violence of protest and uprising in the Soviet republics, as the writ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union shrinks whilst anti-Russian feeling on the Soviet periphery grows.

All of which would have been touted by Russia in Fiction as to some degree prescient had Flames of Heaven been published in 1990 or 1991. What we had trouble getting our heads around was that the novel came out in 1993, by which time everyone knew that the Soviet Union had collapsed, and had done so with remarkably little bloodshed.

But when we did get our heads around the publication date question, Flames of Heaven grew in stature as a convincing portrayal of the pre-collapse Soviet Union, where the enormity of what was to come was not yet grasped even by those close to its unfolding.

Flames of Heaven is a well-written work of over 500 pages, organised into two parts —‘Part One: Moscow, Moscow, Moscow’, and ‘Part Two: the Far Country’. The latter refers to Uzbekistan; although both parts of the novel are set primarily in Moscow and Tashkent, with the addition of an opening few chapters in East Germany, and a memorable interlude in Riga, the capital of Latvia.

These settings match the group of characters around whom Ralph Peters draws his plot, and illustrate the central theme of national identity that came to the fore as the Soviet Union’s end drew near. These central characters, whose lives intertwine and collide as Flames of Heaven proceeds, include: Sasha, a talented Moscow-based artist of mixed Russian-Latvian parentage; Sasha’s estranged brother Pavel, a KGB officer; Captain Samsonov, a veteran of the Soviet-Afghan war; Ali Talala, an Uzbek crime boss and People’s Deputy; and Shirin, Ali Talala’s exceptionally beautiful, Moscow-based student daughter.

Peters takes his time to draw his characters with some depth and clarity, caught up in the changing times of the Soviet endgame. The reader meets them individually before their paths cross; most notably in the lust-fuelled coup de foudre between Sasha and Shirin. And regular readers will know that overly graphic sex and violence is not our thing here at Russia in Fiction; but somehow Flames of Heaven is of sufficient quality in terms of plot, characterisation, and turn of phrase to keep us reading to the end, despite the sexual descriptions being as graphic as we have read, and the brutality likewise. In both cases, any excess is tempered both by being placed in line with the plot rather than ubiquitously scattered, and by being convincing within the novel’s terms.

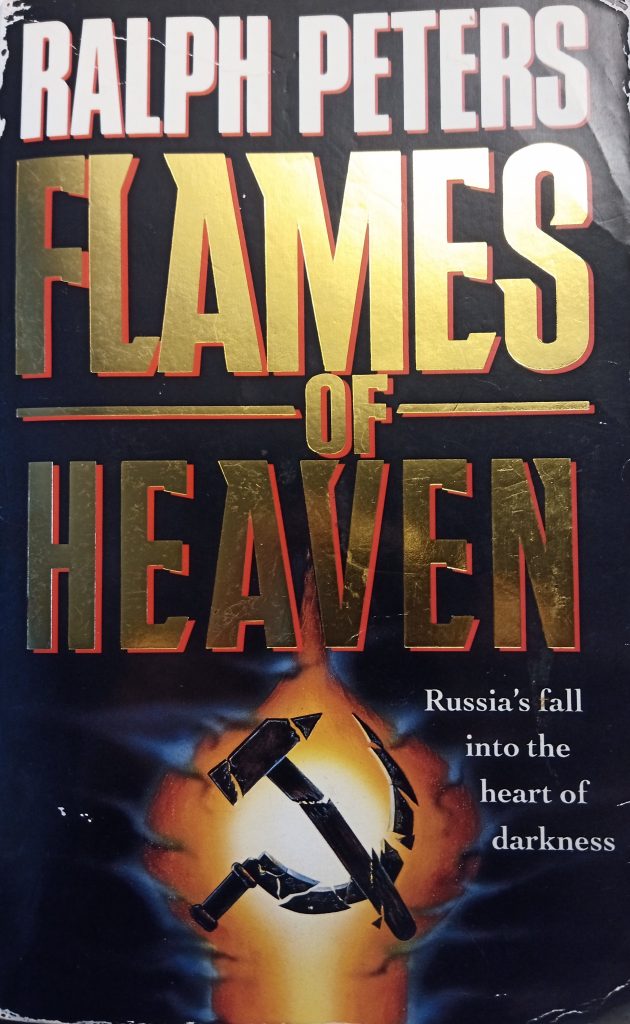

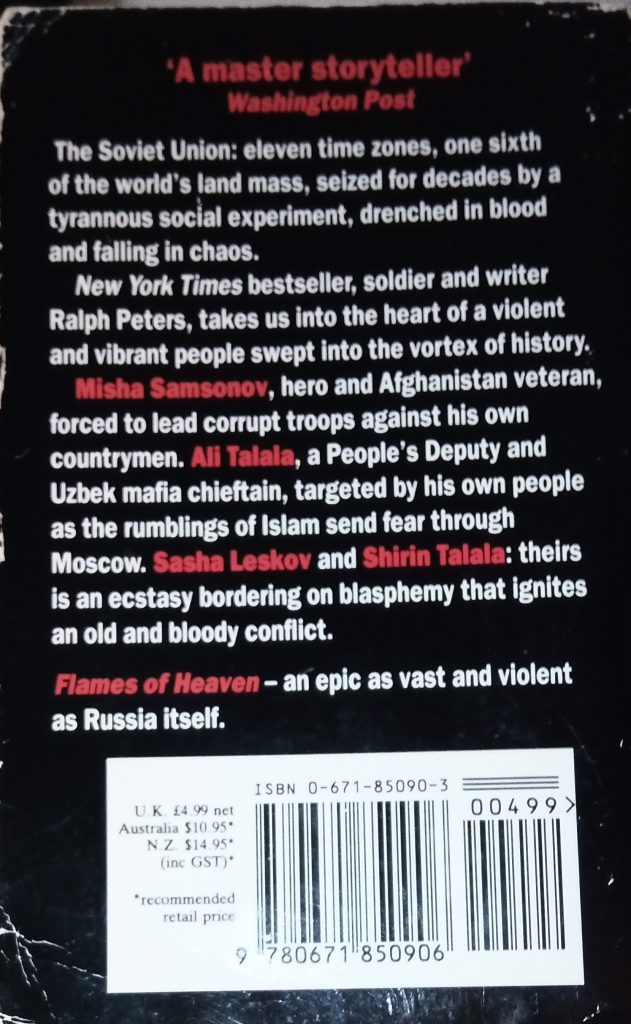

From the blurb on the cover of our Flames of Heaven paperback, Russia in Fiction was expecting something a little more wide-ranging than the novel actually is. ‘Russia’s fall into the heart of darkness’ declares the front cover.

The back cover expands — ‘The Soviet Union: eleven time zones, one sixth of the world’s land mass … drenched in blood and falling in chaos [sic]. Ralph Peters takes us into the heart of a violent and vibrant people swept into the vortex of history … an epic as vast and violent as Russia itself’.

Yes, of course, it is publisher’s blurb, and Russia in Fiction does greet such blurb with the ceremonial bread and a very large pinch of salt.

But nonetheless, the cover of Flames of Heaven suggested a sort of post-Soviet civil war version of Peters’s Red Army.

After all, post-Soviet civil war is not an uncommon theme in Russia-related fiction; for example, Donald James’s The Fall of the Russian Empire (1982), and Monstrum (1997), or Denis Jones’s Russian Spring (1984).

What we get in Flames of Heaven is not exactly small-scale, but its climax is a brief flaring of violence in the minor —and, so far as we can tell, fictional— Uzbek town of Karambul. In Flames of Heaven, national feeling in Uzbekistan and Latvia is accurately portrayed for its temporal setting of 1990, in that talk is more around re-negotiating the Soviet settlement to give more autonomy to the republics that make up the Union, rather than there being an imminent threat of Soviet break-up.

From the perspective of portraying the Soviet Union accurately then, kudos is due to Ralph Peters. He focuses on a distinct group of characters at a specific time, and tells a realistic enough tale, with accurate referencing to the state of the USSR in that period.

A particularly memorable section sees Captain Samsonov, the veteran of the war in Afghanistan, posted back to Moscow to command a battalion of Interior Ministry anti-riot troops, chiefly made up of conscripts. Peters draws a fine picture of the late Soviet-era decay that reflects well the reality of 1990. Morale is low and conditions are poor. Samsonov finds that the battalion armoury’s stock does not match its inventory, since weapons have been sold off. The conscripts under his command have little military skill, since they have been used by the commanding officer to build him a fine dacha. The Quartermaster figure somehow has his own car and an apartment to himself, whilst the soldiers live in delapidated barracks where the plumbing is minimal.

In a particularly nuanced observation that reveals the author’s expertise, Samsonov notes that the dormitories are a little better kept than the wider squalor would suggest, due to the infamous practice of dedovshchina in the Soviet (and later Russian) army. Conscripts, recruited on a biannual basis, would be brutally controlled by the cohort above them, to the extent that they might be little more than personal servants —sweeping their floors, making their beds, cleaning their boots— until they in their turn were able to exert such control over the next group of conscripts.

It is at the level of detail and character that Flames of Heaven impresses. Perhaps misled by the over-selling blurb on its cover, and as ever with an eye to the publication date, Russia in Fiction read the whole novel expecting something more to develop. After all, the book came out in 1993. All of its readers would know that the Soviet state collapsed in 1991. Surely they, like us, expected to be taken to that collapse?

And if that were not to happen in the central plot itself, then, hey, there is an epilogue, so presumably that is there to wrap up any loose ends with the benefit of post-Soviet hindsight? But no, the epilogue, although mentioning the failed August 1991 coup in passing a couple of times, does not even reference the Soviet Union breaking up. It concentrates instead of tying up the detailed loose ends of the novel’s surviving characters.

On reflection, and indeed as we write this review, Russia in Fiction appreciates even more that the strength of Flames of Heaven is precisely in its tightly written nature. It restricts itself to a particular and limited set of characters, none of whom are at the level of high politics or military command, and to a clearly defined period of time, in 1990 after the Berlin Wall has fallen in 1989 and before the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. Its descriptions of that time, as well as of its characters, are detailed and for the most part convincing.

The author clearly knows that the readers know where things are heading, but he insists that his characters can only speculate as to what the future holds. To read Flames of Heaven is indeed to be taken back to that in-between year of 1990. As perhaps the most senior figure featured, a reform-minded KGB General, opines:

‘Our first duty is to survive. To get through all this … every day, every single day, I hear friends and colleagues changing their tunes. Everyone’s scared again. A few years ago, even last year, everyone with a brain was for change. We, of all people, knew the folly couldn’t go on. We had the accurate statistics. We knew how swiftly the West was moving ahead of us. We wanted to modernize, to change, to cast off the deadwood. But not one of us realized the enormity of the task. Not one of us had an inkling of how sick the country was. Not just the economy, but the whole pile of shit. It’s funny. We, of all people, failed to realize the degree to which only fear was holding us all together. We took away the fear. And look. We opened the floodgates a little way, and the whole mechanism collapsed. And now we’re drowning and everyone’s trying to rescue himself …

I’m still for reform. Because I see no real choice. But far more powerful men than me are losing their nerve. No one expected the breakdown. And everyone’s looking for scapegoats …

We haven’t even hit bottom yet. It’s going to get worse. Much worse.’

Flames of Heaven, p. 262