Donald James was a quite brilliant thriller writer. One of Russia in Fiction’s all-time favourites; he died exactly 13 years ago today, on 28th April 2008.

The distinctive trait of his Russia-related novels was to set them in a plausible yet radical near-future. Monstrum was written during the chaotic mid-1990s in Russia. James did in novel form what many Russia-watching analysts sought to do in methodical, scenario-planning form. He took current trends and extended them.

Except Donald James’s version involves a serial killer, love affairs, and betrayal.

Monstrum is set almost a decade on from the time that it was written. Published in 1997, its story takes place in an imagined Russia of 2015, in the dying days of a civil war fought amongst forces representing the variety of political ideas struggling for ascendance in the real world of the immediate post-Communist, early 1990s Russia.

The idea that after Communism, Russia might descend into civil war was not unknown amongst analysts and political figures in the 1990s. In fictional terms it persisted longer, forming the basis for the best known novel by award-winning Russian novelist Dmitry Bykov; «ЖД» (2006), translated into English as Living Souls (2011) by Cathy Porter.

The conceptualisation of post-Communist Russia as a time and place when all ideas were up for grabs, when all the streams of Russian history flowed together into a dangerous whirlpool of chaos, is an astute one. It provides a rich seam for fictional conjecture. The official line of the Yeltsin regime in 1990s Russia, backed up by academic studies and the support of many a Western politician, was that the Russian Federation had embarked on a linear path of transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

Reality was less neat. Russian political scientist Sergei Prozorov writes of this period as a time when every political direction was travelled at the same time; when simultaneously, in political terms, nothing happened and everything happened. There was plenty of movement, but Russia went nowhere.

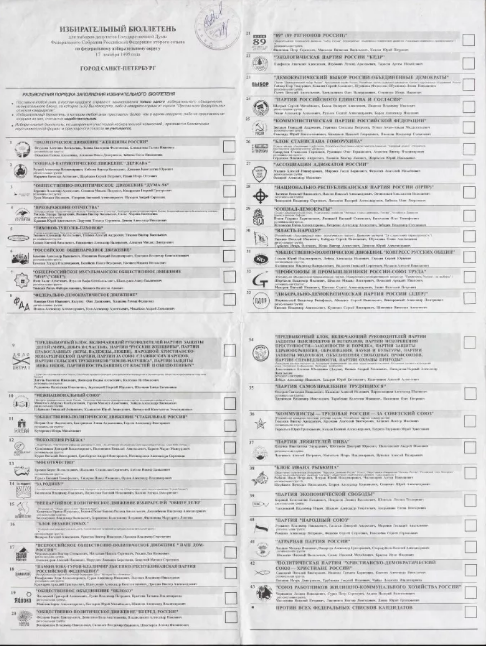

The 1995 general election in Russia had 47 different political parties on the ballot paper, representing almost any line a voter would want to take. Their very multiplicity served to confuse and dilute, blurring the options into a multi-directional democratic splurge.

Just a few short years earlier there had only been ‘the Party’. Now there were too many to count.

Dmitrii Glukhovsky’s Metro novels set still further in the future, in the 2030s, take a similar view of the multiple futures on offer to Russia. Glukhovsky imagines a post-apocalyptic, subterranean Moscow where what remains from the past is that the inhabitants are fractured into many different political groups – the Fascists, the Communists, the democrats, the monarchists, the nationalists, the free-marketeers.

*********

In Monstrum, Donald James has a similar starting concept, and he weaves it into a gripping ‘hunt for a brutal serial killer’ detective story.

Russia in 2015 is ruled by a duumvirate of Professor Peter-Paul Romanov, the nominal President, and a proto-Stalinist who styles himself as Koba (a nickname for Stalin himself) and wields the brutal power behind the throne. These two —representing in their names Imperial Russia and Soviet Communism— led the Nationalist alliance in the Civil War, ‘ the armies of National Democracy’ (p. 4). They have won, but pockets of resistance from the Marxist-Anarchist alliance still remain.

Into this situation, Donald James places Constantin Vadim, a flawed detective from Murmansk, in the Russian Far North. Vadim was to become the hero of a further two novels —The Fortune Teller (1999) and Vadim (2001).

Inspector Vadim has some similarities to Inspector Renko, the hero of Martin Cruz Smith’s Gorky Park and eight subsequent books. He has an inherent caution, oriented to self-preservation before heroism, salted with a commitment to truth. His relationships with women are sincere and deep, but veer from their desired permanence to forced transience. He is one smart detective, but struggles with his superiors’ preference for politics over crime-solving.

At the height of the Civil War, Vadim’s wife Julia had left him, taking their young son with her, to fight for the Anarchist cause. Several years later, in 2015 —the ‘present day’ of the novel— his former wife has attained a status that is dangerous for him.

Vadim, by now working as a homicide detective in Moscow, encounters the only major Western character in Monstrum; Dr Imogen Shepherd is the international ‘amnesty commissioner’ charged with ensuring the ceasefire holds by reassuring defeated combatants that surrender is safe.

Vadim is summoned

‘The amnesty commissioner would like to see you in her office as soon as possible’.

She had taken off the suit jacket she was wearing downstairs … contriving to look professional and efficient and infinitely desirable at the same time

…

‘As amnesty commissioner, I have been examining the files. Of senior Anarchist figures. Among them a certain Julia Petrovna. Highly charismatic commander. Formerly married to a man named Vadim … Julia Petrovna comes originally from Murmansk. Would I be right in thinking …?’

‘It’s no secret,’ I said, ‘Nor is it something I make a point of advertising.’

Monstrum, pp. 175-176

If Imogen Shepherd is to serve as representative of the West, then it is a portrayal of duplicity, untrustworthiness, and a false, almost overstated, enthusiasm for Russia.

Vadim prefers Natalya Karlova, Shepherd’s one-time colleague, a Russian whose take on Russia itself rings true to him.

In Donald James’s imagined Russia of 2015, the Soviet era is referred to as the ‘Golden Age’. Perhaps understandably given the civil war that had followed; and of course to many Russians in the chaotic poverty of the early 1990s, the Soviet era took on a golden-tinged status as a time of stability and international standing.

Natalya Karlova is less convinced.

‘When the Soviet period ended, why was it that so few Russians, almost nobody in fact, dared to ask a simple question?’

‘What question was that?’

‘It’s the question: how could we have had, throughout the Soviet period, twenty million crimes against humanity but only one criminal – Joseph Stalin? Where are all those other hundreds of thousands who committed the crimes for him, who shot and shackled and tortured and faked trials and drove men and women to their deaths? Where are they all?’ She was flushed with anger. ‘Like my grandfather, drawing pensions from the state? Or they were until the Civil War.’

‘Your grandfather had been in Gulag service under the Soviets?’

‘Twenty years as a guard at Magadan. How many hundreds, how many thousands, did he crush to camp dust in his 20 years? My God, he even boasted of the regime imposed on innocent men! And don’t tell me he was obeying the legitimate laws of a legitimate state. The Soviet Union had even less legitimacy than the Russia of the tsars. It was built on a coup d’état. On force and lies. And it continued on that course until the very end.’ She thumped the table in her anger. ‘And I swear to you, Constantin, that Russia will be nothing but the mentally sick man of Europe until we admit our guilt.’

Monstrum, p. 183

To add to its almost encyclopaedic desire to reference Russian tropes, Monstrum also features a long-bearded ‘holy man’. A Rasputin-esque figure, though outwardly more genial than mystic, who oversees a sex cult in the underground passageways beneath Belorusskyi station.

And within all this, Donald James sets out a detective story. There is a brutal serial killer at large —a Russian version of Jack the Ripper— mutilating his victims, who are caught alone at night in the Krasnaya Presnya district of Moscow.

Is it giving too much away to say that by the end of the novel Inspector Vadim solves the case and catches the killer, the titular Monstrum? No, it is not. That is how detective novels work. But the strength of Monstrum is that it supplies much more than the straightforward plot of a detective novel, whilst at the same time still managing to keep that aspect of the book strong.

And from the Russia-in-fiction perspective Donald James delivers by the bucketload. His near-future mapping of the many streams flowing through Russia in the post-Soviet years provides rich fare for those whose tastes are so attuned.

We like Donald James here at Russia in Fiction. It is a strange coincidence —only just discovered as this was written— that our first review of one of his novels is posted on the anniversary of his death.

It will be no coincidence when we publish our review of his most well-known work —the extraordinary The Fall of the Russian Empire (1982)— at some significant marker on our journey to a hundred reviews.

[Update: we published our review of The Fall of the Russian Empire on 9 September 2021].