A novel of Russia. That is the subtitle of Barnaby Williams’s novel Revolution. A subtitle like that is catnip to a blog called ‘Russia in fiction’. But what does it mean?

The phrase ‘novel of Russia’ turns out to be a reliable marker of genre. Several other books of the past few decades carry this marker, and they are all of a type.

‘Novel of Russia’ denotes what might be termed an ‘epic’; a sprawling, multi-generational, hundreds of pages long saga. Revolution begins —predictably enough— in 1917, on the eve of the Communist seizure of power in Russia, and ends as the Communist era itself ends, in the early 1990s, with Boris Yeltsin becoming the first president of a newly independent Russia.

Perhaps the daddy of all these epics, and certainly the best known, is Edward Rutherfurd’s Russka: the Novel of Russia (1991).

Spanning more than a millennium and a half, and clocking in at over 1000 pages in some paperback versions, Russka earns the definite article that precedes its sub-titular phrase.

Only last month, in April 2021, 30 years after its initial publication, was a Russian translation of Russka published.

Set against this, Barbara Scrupski’s Ruslan: A Novel of Russia (2003) scarcely merits that phrase; it is set in late Tsarist St Petersburg and has fewer than 500 pages.

And to get right up-to-date, Nino Haratischvili’s Das Achte Leben (2014), translated into English in 2017 (winning an English PEN translation award in the process) spends a thousand pages covering a near century long tale from the early Soviet era to the early 21st century.

This leaves Joseph Hone’s Firesong: A Novel of Russia (1997) and the novel being reviewed here, Revolution: A Novel of Russia by Barnaby Williams. There are some superficial similarities between the two. Both weigh in at the 700-800 page mark. Both are sweeping sagas that cross the decades and merit the term epic. And both explore the impact of revolution and the tumultuous 20th-century on those who became the particular targets of the Bolsheviks’ class warfare.

Revolution, despite being far less well-known than Edward Rutherfurd’s Russka, was published in Russian in 1997; only three years after its original English version appeared.

Barnaby Williams may take over 800 pages to tell his story, but this review will not detain you long. Maybe it is just that the epic is not a favourite Russia-in-fiction genre? Our review of Firesong by Joseph Hone tests that theory. Whatever the case, there really can be little justification for the overblown front cover blurb that has thriller writer Stephen Coonts proclaiming Revolution

‘a twentieth century War and Peace. Barnaby Williams is the Tolstoy of our times.’

What we have in Revolution is a strongly anti-Communist progression along the route of Soviet history through the eyes of a group of clearly identified heroes and villains. The ‘class of 1917’ graduates of the Empress’s School see their world torn apart by revolution, civil war, collectivisation, and famine. Their tale is punctuated frequently by overly graphic accounts of sadistic brutality and torture, chiefly embodied in the figure of Rykov, who delights in death, pain, and bloody rituals, and finds his amoral ‘talents’ taking him to undreamt of heights and power within the Bolshevik regime. It makes for unpleasant reading.

Williams know the basics of Soviet history, and as we move through the decades, familiar figures flit in and out.

Stalin lauds it over his inner circle, brutalising them and his wife Nadezhda in a version of her death that has the dictator beating and then shooting his wife (as opposed to the accepted version of her suicide, alone in her room in November 1932, after an argument with her husband).

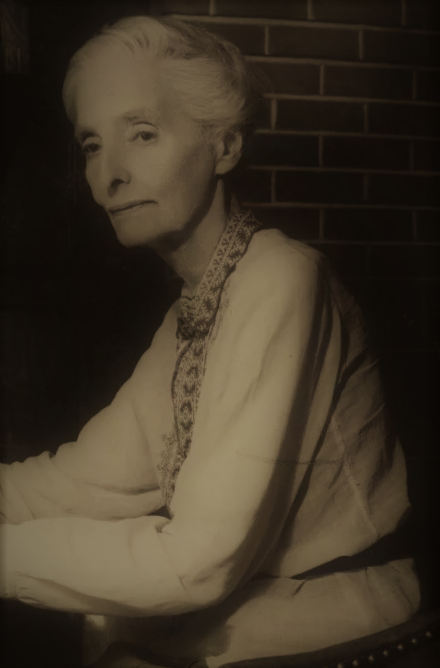

One of Revolution’s central characters, Yelena, meets, in Moscow in 1932, Sidney and Beatrice Webb —the British socialists who have become known as Stalin’s ‘useful idiots’ for their naïve belief that they had been shown ‘a new civilisation’

The Webbs visited the Soviet Union at a time when millions of ordinary people were dying of famine in Ukraine and millions of others were being removed from their farms and sent into forced labour camps in Russia’s remote regions. But they were kept away —both by the authorities and by their own commitment to the Communist ideology— from noticing any of this.

Barnaby Williams has his heroine, Yelena, plead with Beatrice Webb to understand what is really happening

‘They took the grain they had sown on their own land to feed their starving families,’ Yelena said quietly. ‘They found it difficult to comprehend that their land had been taken from them, that they should work to feed others and not their own, for no reward.’

‘Exactly,’ said Webb. ‘Greedy, cunning and dishonest … Lenin, and now Stalin, artists who work in men as others work in marble or metal. So shavings and dross lie on the floor, but is not the product wonderful?’ …

‘Mrs Webb, I’m sorry if I am annoying you. But has it never occurred to you … That your visits here are about as spontaneous and free-ranging as a railway and its timetable? That you see what your hosts wish you to see, that you speak only to those whom your hosts wish you to speak?’

The Englishwoman smiled incredulously. ‘What an extraordinary notion!’ She said loudly … She looked over Yelena’s shoulder. ‘Ah. Sidney, there you are,’ she called.

Revolution pp. 320-321

There is much more in this vein. Historical figures move in and out, their heroism or villainy spelt out and amplified. Beria of course makes his appearance, raping victims nightly. The idea that Stalin may have been helped to die at his last is not hinted at, but set out plain, as members of the Politburo suffocate him with a cushion.

Russia in Fiction could go on, as indeed does Revolution: a Novel of Russia, through the atrocities of the Russian Civil War and World War II. We get taken up to the highest levels of government with Roosevelt and Churchill in 1945, and with Khrushchev and Kennedy in 1962 as the Cuban missile crisis unfolds. Characters find themselves in Budapest in 1956, as the Soviet tanks roll in.

With a little over 50 pages of the 800+ pages to go, the novel is only in 1969 and so it all seems a little rushed to get to the Soviet collapse and the rise of Yeltsin in 1991 before the end. Surely another couple of hundred pages could have been written?

But wherever we are in the saga, Barnaby Williams always finds space for the most gruesome and graphic accounts of torture and sadism and rape.

35 pages from the end and we are still only in 1983.

Quick, bring in Gorbachev and explain what needs to be done to get to the Soviet collapse!

So Williams imagines, in a couple of pages, the dying Soviet leader, Yurii Andropov, introducing Mikhail Gorbachev to an economics expert from Novosibirsk, Tatyana Galina Serebryakova.

Subtle it is not.

‘I’m dying,’ the General Secretary said …

There was another man in the room. He stood up, short, stocky and balding, with a vivid birthmark on his head, where his hair had been …

‘This is Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev,’ Andropov said … I had intended Mikhail Sergeyevich to succeed me as leader of the Soviet Union,’ said Andropov. ‘However, the doctors say I shall surely be dead. Chernenko will succeed me, but as he is but a dead man on furlough himself, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev will, within one or two years at most, be in charge.’

Revolution, p. 784

The economist, Tatyana, then proceeds to explain to Gorbachev how bad the situation in the Soviet economy is.

She reads to him from the Communist Party Programme of 1961, which had claimed that by 1980 the Soviet Union would have in the main attained to what Communism promised.

‘Before 1980, it specifies, there will be so much food that everyone will be fed free of charge. Housing, gas, water, electricity, heating and transportation will be free of charge. All citizens will have two months free and luxury holiday a year, and will spend glorious and long years of retirement tended for by free medical and social services.’ …

‘What are the realities of life in the Soviet Union in 1983? … The Soviet Union is the only industrialised nation where death rates are rising. The average Soviet male can expect to live for only 60 years, six less than 20 years ago. Equally unique is the rise in infant mortality —three times the rate of the USA and increasing. If this continues, the Communist Party will preside over the extinction of the Russian people …’

An expression of shock, followed by anger, appeared on Gorbachev’s face.

‘Communism remains the most efficient system of both government and production,’ he asserted flatly. The socialist system has immense untapped potential for improvement. What is required is perestroika, a reconstruction and a strong and imaginative leadership.’

Revolution pp. 784-785

Not quite Tolstoyan prose.

Russia in Fiction has a measure of admiration for anyone who can keep the threads of a saga hanging together across several decades and 800 pages. But the epic —at least as exemplified here— does not appear to be our sort of thing.