In Firesong, noted writer of espionage novels Joseph Hone (1937-2016) tries his hand at the sprawling epic; 700 pages following Prince and Princess Rumovsky, members of the St Petersburg nobility, in the tumultuous 14 years between New Year 1906 and Christmas 1920.

Firesong is then a ‘Russia in the time of revolution’ novel. Like others of this sub-genre —Barnaby William’s Revolution (1994), James Meek’s The People’s Act of Love (2005), Charlotte Hobson’s The Vanishing Futurist (2016)— Firesong sets up the pre-revolutionary life of its central characters and then explores the impact of revolution and civil war on the same.

The epic is not Russia in Fiction’s favourite genre. That said, there is plenty here to fascinate and to enlighten from the Russia-in-fiction perspective. Not least, we learnt stuff about Harbin.

Joseph Hone was a highly rated but too-little-known author of espionage novels in the 1970s (see our review of The Sixth Directorate). By the late 1990s, Hone had left the tightly plotted spy novel behind and he produced a family saga that touches on a wide range of Russia-related themes.

At different points in its 700 pages Firesong brings to the fore different aspects of Russian life and culture. Alongside these Russo-specific elements, the story is one of love and sex and revolution and war, centred around Yelena Rumovsky and her twin brother Sasha as they come of age at a time when the world they knew was destroyed forever in the violence of civil conflict and an ideologically-driven overthrow of the old regime.

The Russia that Firesong first depicts is a somewhat fantastical land. The year is 1906 but the temporal setting portrays Russia from almost any time in the preceding few centuries, as the children Yelena and Sasha —with their parents, their governess, and a collection of servants— speed in their troikas across the frozen landscape of northern Russia, and the frozen Lake Ladoga, towards their grandfather’s fairy-tale-esque castle to celebrate the New Year.

Grandfather, Prince Mikhail Andreivich Rumovsky, is a boyar from a long-standing noble line, whose writ appears to run across a vast territory in Karelia. Hone draws the contrast between Prince Mikhail, and his son —Yelena and Sasha’s father— Prince Pyotr, who is a liberal member of the new Duma (parliament) in St Petersburg.

A fur koshniki, ringed at the bottom with gold and silk thread with a crust of glittering opal and turquoise stones above that, sat on his head like a crown. Prince Mikhail Andreivich Rumovsky — wrapped in his gleaming sable … sat now on his throne atop the dais with all the air and dress of a Tsar from another age.

Which indeed, so far as this huge territory went, he was. The Prince was absolute master here, as his Rumovsky ancestors before him had been … The writ of Empire, though formally posted, was not the law that mattered here. This was Rumovsky law.

Firesong, p. 19

As for the old Prince’s children, including Prince Pyotr, they

… had long since left and rarely returned to this medieval fortress … they were modern people, who had gone out into the new commercial world of Russia.

Firesong, p. 22

Hone uses descriptions of fashion to illustrate the generational gap between the old prince with his retinue, and the more modern, western following generation. At the New Year celebrations, the former are dressed in elaborate silk shirts and fur-trimmed kaftans, ‘in the fashion of days long before’. In contrast, Prince Pyotr wears a tail-coated evening suit, with a starched shirt, high-winged collar and bow tie.

Inevitably, the liberal, metropolitan Pyotr argues with his father.

The old Prince gave a smile of feigned astonishment. ‘Who but I —in this vast land— can hold the law? That is exactly my duty … My way is the true way — of the land and of the people. Mother Russia was ever thus. She draws her very being from a strong father, and can never do so from half a dozen “leaders” — weak and foolish “politicians”, squabbling and disagreeing in the Duma. That will bring nothing but the destruction of the Empire, in riot, revolution, war.’

…

‘Father, you are living in the distant past. The serfs were freed over forty years ago.’

The old Prince laughed. ‘Yes, and how many of them wished they hadn’t been?’

Firesong, pp. 43-44

Thrown into Firesong’s engagement with Russia’s past is the theme of the mystical and spiritual, of soothsayers, the great wind god Bieggolmai, Baba Yaga ‘the worst witch of all’, and gifts of second sight and healing.

Themes of this nature are at the heart of Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, and that is set half a millennium or more before Firesong.

(Russia in Fiction will review the first in this trilogy, The Bear and the Nightingale (2017), before we reach a hundred books reviewed).

Update: The Bear and the Nightingale was reviewed in September 2022.

Caught between these worlds of the traditional and the modern is Yelena. She has these unnatural gifts, and at the same time she and Sasha grow up in western-oriented pre-revolutionary St Petersburg, where they become accomplished classical musicians.

Yelena, as she grew older, came to hate Russia. Troikas, wolves, gypsy balalaikas, the tolling bells from blue-domed churches, snowy visions, holy men and monsters, peasants in red kerchiefs. All that had seemed natural and happy to her before now became hateful.

…

There was a whole world to the west, beyond the frontier station at Wirballen, which she knew about from holidays to Paris, Berlin, Nice, Biarritz. A modern world. Sensible, organized, reliable … Russia wasn’t modern and never would be.

Firesong, p. 53

Firesong begins then with the Slavophile / Westerniser tension; a Chekhovian sense of a world on the turn. But then, being an epic saga, the narrative is bound to widen and follow historical events. This binary division is multiplied with the advent of the First World War, followed by Revolution, followed by Civil War. And these events are simply settings for the novel’s multi-stranded plots that are all centred on love and romance and sex.

To take Yelena —as she is Firesong’s fulcrum, though by no means the only character whose story unfolds across these pages— she falls for an American entrepreneur, a Bolshevik-oriented agitprop performer, and a British diplomat; all at the same time as being closer to her twin brother Sasha than might be seen as healthy. It is not too much of a stretch to see Russia’s potential futures in the early 20th century personified in these possible partnerships.

With Revolution comes the nobility’s end, and a flight across a Russia caught up in the vicious Civil War between Reds and Whites. Hone sets much of the novel’s penultimate part (‘Book Four, 1919-1920’) in the town of Harbin, in China, which in the Civil War years became a place of refuge and settlement for those driven out of Russia by the advance of Bolshevism.

Harbin grew rapidly in the first decades of the last century, to have by 1920 a mostly Russian population of over 100,000. Arriving there, Yelena is amazed to see what approximates to a pre-revolutionary Russian city.

FILIPOV’S PIROSHKIS. She looked up at the sign. They had been famous throughout Russia before the revolution. She and Sasha had eaten them almost every day in winter from street stalls or at Elysieff’s café on the Nevsky Prospekt

…

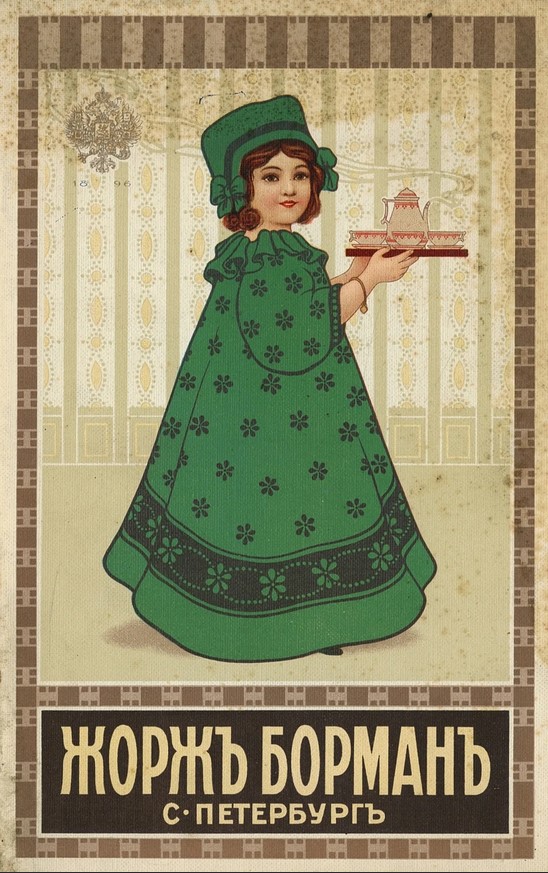

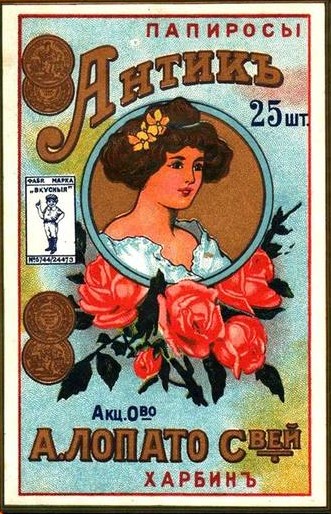

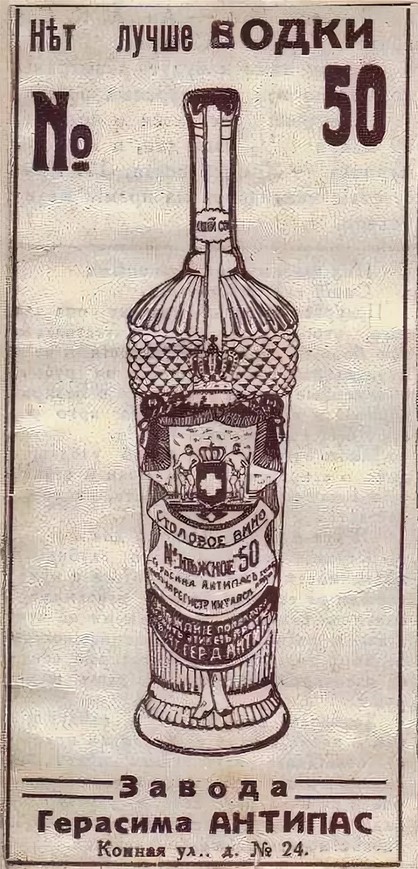

She gazed at other shop windows … seeing the hoardings on the street corners advertising things she no longer thought existed: BORMAN’S CHOCOLATE, LOPATO CIGARETTES, GERASIM’S VODKA.

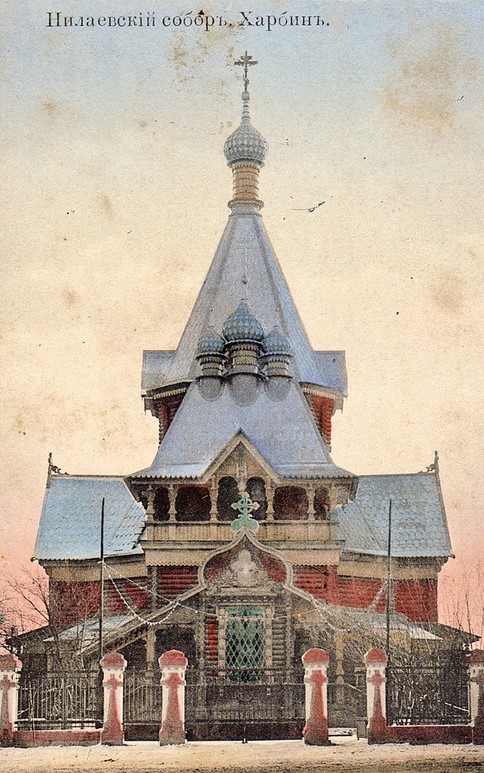

She still could not quite believe it all: this vast, throbbing city, with its tramcars and motors and throngs of well-dressed people; its blue- and gilt-domed churches, and the Cathedral of St Nikolayev just ahead of her now, built in the Old Volga style. A city which was part of a lost time, she saw, as well as being an eldorado now, set in the middle of Manchuria.

Firesong, pp. 529-530

Russia in Fiction is grateful to Firesong for enlightening us about the history of Harbin, and a world of Russian émigrés far distant from the better known lives of their contemporaries in Europe.

***************

Firesong, like the other Joseph Hone novel reviewed by Russia in Fiction, ends in the English Cotswolds (‘Epilogue: Christmas 1920’). This happens to be where Joseph Hone lived for most of his adult life.

How did an epic saga of Russia in turmoil end up in an idyllic Cotswolds rectory at Christmas? Well, Firesong is nothing if not an artifice. The epilogue provides rather a mawkish ending, tying the complexities of multiple relationships together in a somewhat sugary manner; every character paired off appropriately, village life as if scripted by Laurie Lee with music by Ralph Vaughan Williams. Characters aside, the epilogue bears almost no relation to the elemental nature of the ‘novel of Russia’ that precedes it. May be that contrast is precisely the point?

Whatever Joseph Hone’s reasoning behind this unlikely ‘Christmas in the Cotswolds’ ending, it turned out to be seasonally appropriate reading for Russia in Fiction during these festive days.