The People’s Act of Love, once read, forms impressions in the mind. Innovative in its setting, memorable in its characters, inventive in the slow-burning complexity of its plot, and deploying language with the savage precision of a cavalryman’s sword decapitating an enemy at full charge; James Meek’s novel delves into lives lived in extremis, as its characters act and love and seek to merge the two.

What is an act of love? Selfless? But selflessness is mediated through self. People do not act alone in an abstract world, be that the abstraction of Marxist ideology or of sectarian theology. Actions affect others, whether they are as close as a spouse or as distant as nameless, unborn, future generations.

Russia in 1919. The year that Boris Pilnyak called The Naked Year, the year in which the cumulative crushing force of World War, Revolutions and Civil War stripped away Russia’s civilisational veneer, leaving its people in elemental states of being.

The People’s Act of Love is set in the small, fictional Siberian town of Yazyk. The Russian Civil War is in full flow.

“It’s a different kind of war. One where you can’t understand who is on which side. In the old war, the one against the Germans and the Austrians, it was ours against theirs. Now it’s more ours against ours. There are Whites and there are Reds. The Whites are for the Tsar — he’s dead now, the Reds killed him — and the Reds are for everybody being equal.”

The People’s Act of Love, p. 27

But James Meek’s novel populates Yazyk with characters who do not fit this easy colour-coding of conflict.

Samarin is an escaped convict of revolutionary bent, but with a ferocity of individualism that would not act easily within the confines of Party discipline or doctrine. He exhibits a confused and conflicted passion that stands in contrast to the rule-bound, symbol-heavy portrayal of the Communist soldiers that Meek depicts.

In London and Paris and New York they saw the Reds as an anarchic, destructive, turbulent menace which demanded to be controlled … Here [he] saw only a new order, a new empire, coming to take its place amongst the old.

The People’s act of Love, p. 280

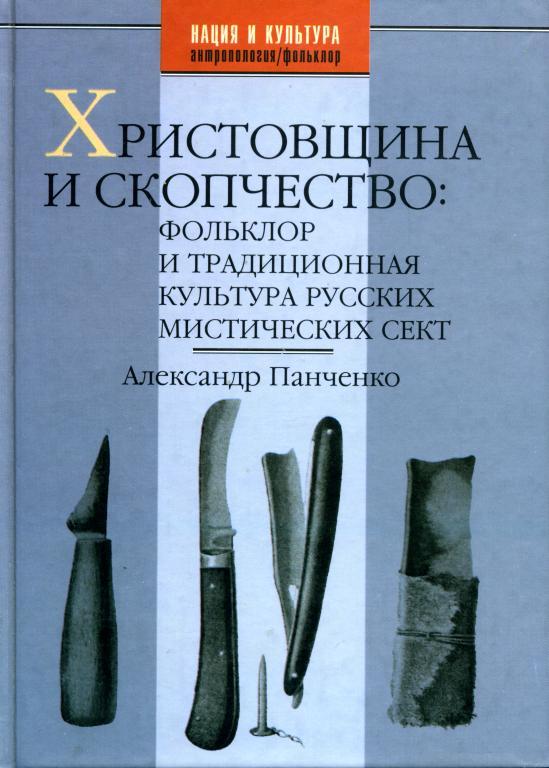

Balashov is a former cavalryman in the Imperial Army whose experience of war prompted his God-fearing inclinations to move from the spiritual to the elementally physical act of joining a sect that practised voluntary castration to divest themselves of sinful urges.

Anna is his wife, previously sexually awakened and satisfied by her virile cavalry officer husband, she then —after learning of his self-mutilation— arrives in Yazyk with their son, living incognito and sexually frustrated in a town of castrates.

The other inhabitants of Yazyk are the remnants of a battalion of Czech soldiers, whose only route home would seem to be to all but circumnavigate the globe, travelling back to Central Europe via Vladivostok and the crossing of the Pacific Ocean, the United States, and the Atlantic.

Prominent amongst the Czechs are their drugs-and-power addicted commander, Matula, who would happily keep his men where they are, acting out dominion over his own isolated fiefdom in the middle of Siberia; and Mutz, the Jewish Lieutenant and embodiment of the sensible actions and attitudes common amongst the European petite bourgeoisie.

James Meek knows Russian, having being The Guardian’s Moscow bureau chief in the second half of the 1990s. Meek also knows his Russian history. The castrates are based on the skoptsy sect, and the Czechoslovak Legion was finally evacuated, in its tens of thousands, from Vladivostok in 1920. As Lieutenant Mutz puts it:

‘the Legion isn’t an army… It’s fifty thousand travellers waiting on a platform for a delayed train home.’

The People’s Act of Love, p. 157

Alongside these central elements, The People’s Act of Love draws on vignettes of Russia’s flawed revolutionary endeavours that illustrate how grand purposes become enmeshed with personal vanity. Samarin’s uncle had taken part in the

mad summer of 1874 … one of the students who went like missionaries among the peasants in the villages, urging them to rebellion. The peasants had no idea what the students were talking about, suspected they were being mocked, and asked them, with embarrassed whispers and some jostling, to leave.

The People’s Act of Love, p. 2

Anna’s father, a portrait painter in the Voronezh region, had deliberately insulted a local landowner during the unrest of 1905.

Her father was imprisoned for two days. He wasn’t sent to Siberia, fined or tried … But it was 1905 and the marshal of the nobility was cautious. The council was a nest of liberals, the army used artillery on the streets of Moscow, peasants were setting fire to landlords’ properties … When the marshall’s own daughter told him that she wasn’t welcome in some of the best houses in town because he had arrested the artist Lutov, he arranged for Anna’s father to be let go.

Anna’s father … continued to believe that of all the heroism shown in the struggle for freedom in 1905, his had been the most extraordinary. His family saw little of him, and dust gathered on his palette and brushes, while he smoked poods of tobacco and drank Turkish coffee with liberals and revolutionaries in dark restaurants and stuffy conspiratorial flats.…

Anna’s father began spending time at a house that acted as a night school for young women who wanted to learn about Marxism. He was able to talk about Marx to them with more eloquence and conviction than they could muster because he wasn’t hampered by any knowledge of the great thinker’s writings.

The People’s Act of Love, pp. 78-80

These references to events in 1874 and 1905 plant early seeds in the novel’s exploration of how the self-centred acts of individuals mesh and clash with worldviews and grand narratives. They bring a measure of freshness to the tired old trope that the abstract ideals of Russia’s Marxist revolution fell repeatedly at the hurdles of individual actions and interpretations.

And The People’s Act of Love wants to make this a wider observation, not merely confined to Soviet Marxism. James Meek sympathetically draws cavalryman-cum-castrate, Balashov, on his journey from soldier to pacifist. But its diversion to self-castration deprives Anna of her husband and their son of his father.

It is a great strength of The People’s Act of Love that the novel does not deliver some clichéd playing off of Balashov’s mystical religious sectarianism against Samarin’s rational revolutionary enlightenment, but emphasises instead their commonality, as frail individuals fail to fully enact the higher purposes that they embrace.

Samarin finds that his love for a woman prevents him acting with the ruthlessness which his abstract notion of liberation for future generations demands.

Holed up with Balashov in a remote stable, his self-frustration once again seeks action.

‘I went back, for the sake of that woman … It must not happen again. You reach the moment of it must not happen again, for the sake of a better world than this miserable one. Now I’ve reached it. Take the knife. Take it. Castrate me … Castrate me, Gleb … Or I’m no good to the future.’

The People’s Act of Love, p. 363

The People’s Act of Love delivers a powerful narrative of elevated ideas playing alongside elementally physical acts. Russia, indeed remote wintry Siberia, in 1919 provides an appropriate, superbly realised setting for their exploration.

Read this novel and you will not forget it.