Voronezh, Voronezh, Voronezh. Three reviews in a row take Russia in Fiction back there. Though this central Russian city diminishes as we progress. In Black Earth City, Voronezh is the central character. In JUDAS 62 it is the location of the origin plot. In Chameleon, the subject of this post, it is merely the site of a murder that forged the reputation of Mark Burnell’s main Russian character, the oligarch-cum-mafiya boss, Kostya Komarov.

Burnell’s wonderful Petra Reuter tetralogy was published between 1999 and 2005. Here at Russia in Fiction we have re-read them several times, and have learnt to take care when picking up the first in the series (The Rhythm Section), as it usually means reading the four book series all the way through.

The series as a whole is not specifically about Russia, but in Chameleon —the second in the series— Russia comes more to the fore, in the character of Kostya Komarov.

To set the background, The Rhythm Section (1999) tells the story of the macabre redemption of a young English woman, Stephanie Patrick, working as a drug-addled prostitute in London after the death of most of her loving middle-class family in a terrorist bomb had led her, blind with grief, to throw off her normal life as a university student.

In the course of the first novel in the series, Patrick ends up working for a secret, off-the-books UK government agency, which trains her as an assassin, adept at killing selected undesirables and living a life of multiple identities, most notoriously that of Petra Reuter, a German-born contract killer of international repute.

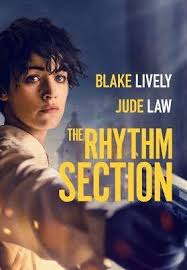

The Rhythm Section was made into a movie, also penned by Mark Burnell. It didn’t reach the heights of the novel on which it was based. John le Carré used to say that when his books were turned into films, he learnt to turn them over completely to screenwriters.

On the written page, Burnell’s plotting, writing style, and characterisation just hit the sweet spot. There is a self-deprecating, knowing vein throughout his stylish and action-packed novels. Whilst not wanting to over-generalise along the lines of nationality, there does seem to be something very English about Mark Burnell’s thrillers.

The Russia interest in Chameleon comes in the form of tatooed, super-rich Kostya Komarov; from a vor v zakone background, but forging his own distinct way in post-Soviet Russia and beyond.

At first glance, Komarov is a bad guy —a Russian mafiya boss of oligarchic wealth with an international jetsetting lifestyle and a reputation as a man quite capable of taking out his enemies. His nickname is ‘the Don from the Don’. Although he is a Siberian based in Moscow, that nickname comes from an incident in 1993 when an Uzbek moneylender was murdered in Voronezh.

As Chameleon progresses, so the picture of Komarov the bad guy is increasingly undermined. We read of his childhood in Siberia, of his years in Soviet prisons, of the code of behaviour of the Russian criminals known as the vory v zakone; a state-rejecting code that in its own way insists on honour and fealty amongst thieves.

But even this deeper characterisation is not enough for Mark Burnell. Komarov is slowly revealed as a genuine philanthropist whose position in the criminal world and whose very character contribute to a desire to do his significant good works in secret. Robin Hood without the publicity.

The relationship between Petra Reuter and Kostya Komarov dominates Chameleon and remains a presence through the final two books in the series —Gemini (2003) and The Third Woman (2006).

Chameleon is a fast-paced and action-packed international thriller. Its Russian elements are frequent but not dominant. At first they draw mainly on the Russian émigré community in New York and New Jersey.

There is a lovely chapter from the Russia-in-fiction perspective (Chapter 10) set around a visit to an Alla Pugacheva concert in Atlantic City,

Alla Pugacheva, the popstar of the Soviet era, a cultural icon with album sales of more than 200 million. Brash, brassy, and possessed of an undeniable voice. Starting as a teenager in the 1960s, through the 1970s and 1980s she survived and prospered, eventually outlasting the system with which she was associated.

‘To understand Alla, it’s not enough to be Russian,’ Maria sighed, as they hit the outskirts of Atlantic City. ‘You have to have lived in the Soviet Union.’

Chameleon, p. 166

Two thirds of the way through the novel, the setting becomes Moscow itself.

Russia appears without warning. The Lufthansa aircraft dropped out of dense cloud and suddenly there’s land beneath me but no colour; it’s all pewter and coldness. I’m flying over a jigsaw of lakes, rivers, birch forests, small farm holdings

Chameleon, p. 285

[For the record, in case you are wondering, the novel is not written in the first person, although there are recurring sections —indicated by italics— that are.]

As regular readers of this blog know, Russia in Fiction is always unaccountably cheered when a character checks into a hotel where we have stayed. In this case it is the Baltschug Kempinski, just across the river from Red Square, opposite all time favourite and often mentioned , ‘gargantuan Hotel Rossiya’ (p. 289), which was demolished in 2006.

But Moscow settings are not confined to city centre hotels, there are well-drawn scenes in the Izmailovo market and in the tatty high-rise apartment blocks in the micro districts of Bibirevo and Krylatskoye Hills.

Written in 2002, Chameleon expresses early doubts, through the mouth of Kostya Komarov, about the Putin regime.

‘This country goes from one crisis to the next. Look at something like the sinking of the Kursk. That was a tragedy. It was also good TV: all the weeping mothers gathered in Murmansk, Putin showing his true colours, that old KGB mentality. We read about one environmental catastrophe after another and we blame the Soviet past. But the biggest tragedy in Russia today is ongoing. It’s the collapse of the future. Children without homes, without education, without medical care, without parents. And children who would be better off without the parents they have. I’m a businessman, Petra. An investor. And I’m investing in the future. That’s all.’

Chameleon, p. 338

Away from Moscow, there is an enjoyable scene in London, where Petra/Stephanie is following a Russian oligarch target.

She followed him at a discreet distance. He crossed the Euston Road, walked down Judd Street as far as Tavistock Place, where he turned left …

By ten fifteen, they were at the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Ennismore Gardens …

At eleven, Stephanie found herself on a street of terraced houses in Kennington …

At Kennington Underground, he took the Northern Line to Moorgate, from where he walked to Finsbury Circus. At quarter to one, Vatukin return to Moorgate …

He caught the Northern Line to King’s Cross and the Victoria Line to Green Park. Just before one thirty, he entered Diverso, an Italian restaurant on Piccadilly, where Natalia and the two minders were already at a table. The afternoon was a retail orgy; Asprey’s, Cartier, Hermes, Prada, Armani. They spent an hour in Graff being fawned over. Stephanie spent the same hour on New Bond Street being rained on. Watching, waiting. Gaudy Christmas decorations sparkled in the rain. When they emerged, Natalia looked smug. Vatukin looked bemused. In Moscow, the bodyguards carried weapons. In London, they carried shopping bags

Chameleon, pp, 348-349

This fairly stereotypical picture of Russian oligarchs, and ‘new Russians’ in general, presents a contrast to the figure of Kostya Komarov.

As observers of Russian affairs will recall, apologists for the oligarchs in the 1990s would make the argument that Moscow in that decade could be compared with Chicago in the 1920s, and that eventually, the brutal disregard for the law that characterised much business in Russia would give way to a wider law-based prosperity. In Chameleon, Mark Burnell has no time for this argument.

‘The new Russians don’t care about anybody but themselves. They take as much as they can and the rest of the world can f*** off.’

‘But not Kostya.’

Ludmilla shook her head.

‘He comes from a tradition that used to rob the rich to help the poor. The new Russians rob everybody —especially the poor— and keep it all for themselves.’

‘Maybe that will change.’

‘Not any time soon.’

‘One day,’ Andrei said, ‘when they’ve bought everything else, it might occur to them to spend some money on a lasting legacy. But not yet. They’re not ready. They think philanthropy is something dirty their girlfriends do to them.’

Chameleon, p. 425

As is the nature and purpose of reviews on this blog, the focus is on Russia in the fiction. There is a lot more than this to Chameleon and to Mark Burnell’s novels in general. The whole Petra Reuter tetralogy hits the spot effortlessly. Chameleon is the most Russia-focused in the series, and we single it out for this reason alone, and not because it is better than any of the other three books.

If you like thrillers and don’t yet know Mark Burnell’s work, then don’t wait any longer. You are in for a treat.