One of the aims of the Russia in Fiction blog is to get a sense of how Russia is portrayed in English-language fiction over time. What are the themes that come to the fore in different periods? What are the constants? And how realistic is any of this stuff?

One thing that we didn’t expect to find when we started out was quite the number of ‘Chernenko-era’ books that there are. We have written about this before at some length, and don’t want to re-hash all of that here. (Have a look at the review of Russian Spring (1984) by Dennis Jones for more details).

Moscow Rules is another thriller set in the year of Konstantin Chernenko as leader of the Soviet Union (1984-85). It stands out because it recognised, ahead of the events, that the Soviet system was heading to a swift end.

Like Russian Spring (1984) and like Donald James’s The Fall of the Russian Empire (1982), Moscow Rules is a fictional account of what it saw coming soon, firmly established on the view that the authoritarian Communist Party of the Soviet Union could not hold its ever-weakening grip on the nations of the Soviet Union for much longer.

What is interesting is how few Russia analysts, as compared to fiction writers, appear to have countenanced the collapse of the Soviet Union in the first half of the 1980s. The freedom of fiction allowed to be realised on the page what the policy world thought unthinkable, but what was soon to come to pass.

If you are a regular reader of this blog, and think that you recognise the name of Robert Moss, then that’s because it features in our pithy summary of the best Cold War era espionage writers: John Le Carré, rhymes with Charles McCarry, and add a couple of Bobs (Robert Littell and Robert Moss).

With that set-up, you know that Moscow Rules is a stand-out of its type.

The plot of Moscow Rules follows the rise of a dissident Russian army-cum-GRU officer, Alexander Preobrazhensky, from his teenage disillusionment with Communism, through a determination to see Russia re-born, via training in the spetsnaz special forces, a posting in luxurious New York, and a tour of duty in war-torn Afghanistan, to eventually the culmination of his years of patient plotting, a coup attempt as the Politburo seeks to appoint Chernenko’s successor.

Moscow Rules was written before Chernenko died and his real-life successor —the young reformer, Mikhail Gorbachev— was appointed. So whilst the scenario set forth by Moss did not play out in quite the way he imagined it, with the benefit of hindsight we can see that Gorbachev’s six years in office eventually led the Soviet Union, and Russia itself, to a similar place as that towards which the fictional General Preobrazhensky strived. Though with one key difference.

The key difference in question also marks the least convincing element of Robert Moss’s plotting; specifically, the idea that effective and decisive opposition to the country’s leadership would come from the military. There is no real history of military coups in Russia. Such coups as have been attemped in Moscow have invariably come from governing political figures within the regime.

The August coup of 1991 may have included Defence Minister and career military man Dmitrii Yazov in its ranks, but it was conceived and led by civilians.

Ditto the turfing out of office of Nikita Khrushchev in 1964 and the more brutal removal of Lavrentii Beria from any hope of succeeding Stalin in 1953.

In Moscow Rules, Robert Moss has the Chief of Staff as a member of the Politburo (p. 331). In the Soviet system, army officers were not part of the political leadership and no Chief of Staff would be a Politburo member.

That point aside, the many strengths of Moscow Rules include its knowledge of the Soviet system, its descriptions of Moscow, and its occasional forays into colloquial, and very course, Russian slang.

Preobrazhensky comes of age in the Khrushchev era, the son of a devoutly —if sourly— Communist mother and a deceased war hero father. Through an encounter with a Jewish intellectual neighbour, and a subsequent coup de foudre, that grows into a life-long love, with his daughter, Preobrazhensky is at first drawn into the world of reckless dissidents. Later he decides that the most effective opposition to the regime he despises must come from within the system itself, and sets himself to rise to a position of influence through the Soviet army and its intelligence service, the GRU.

Moss, an Australian who became an academic and then a think-tank analyst and journalist before writing fiction, knows his Soviet history and politics. He makes use of the difference, and indeed rivalry, between the GRU and KGB. He understands the economic situation. He is aware of a strong undercurrent of Russian nationalism in society that, however powerful the Soviet Union is, still sees the Communist regime as alien.

The minor character of Captain Zaytsev provides a useful mouthpiece:

‘There never was a Russian revolution. We’re still waiting for it … In the key group of five men that seized Russia,’ Zaytsev went on, ‘there were three Jews —Trotsky, Kamenev, and Zinoviev— one cockroach from Georgia, and our famous Lenin, who was half-Kalmik and half-German Jew’.

Moscow Rules, p. 109

‘Lenin decreed that the land belonged to the tillers, am I right? Then, the very next year, he imposed a new law, saying the land belonged to the state … the peasants would have to turn over their crops for free … they brought in the collective farms as part of a plan to destroy the successful peasants as a class … Fifteen million of them were shipped off to plough tundra in Siberia. Most of them died …

We’d all go hungry if someone hadn’t woken up and decided to let the kolkhozniks have a little scrap of land of their own to work in their own spare time. Those private plots are may be three per cent of the farmland in Russia, and they produce a third of our meat and milk, and two-thirds of our potatoes.’

Moscow Rules, pp. 107-108

Granted, it might not be the most convincing of dialogue. But Moss knew his stuff back in the mid-1980s. If there were two reasons behind the collapse of the Soviet Union that was to come in 1991, they were nationalism —including Russian nationalism— and economic decline.

There is much more to Moscow Rules, plot-wise, than the high-level summary above. This is no pot-boiler of a book, but a classy piece of thriller writing, with multiple sub-plots, strong characters, and convincingly drawn developments.

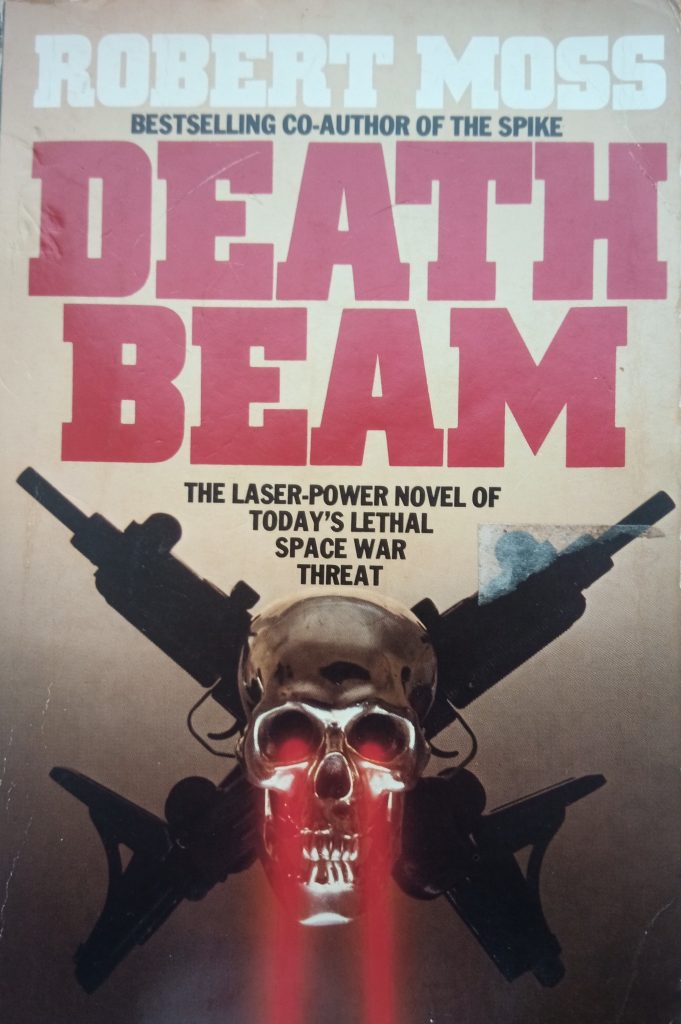

Robert Moss wrote other Russia-related thrillers, notably The Spike (1980) —with Arnaud de Borchgrave— which was the first book reviewed on this blog, and then Death Beam (1982). By the end of the 1980s, Moss had moved on, and he has for many years been a writer and speaker in the realm of Shamanic dreaming.

One presumes that Robert Moss didn’t realise quite how the dream of Soviet collapse set out in Moscow Rules would become reality only half a dozen years later. But may be he did.