Joseph Hone, ‘the most unjustly neglected spy novelist of his generation’. So said Hone’s obituary in The Telegraph (23 September 2016).

From the Russia-in-fiction perspective, The Sixth Directorate opens with a prescient view of what a few —though I think not many— observers of the Soviet scene with astute foresight were thinking possible in the mid-1970s. Surely, such apparently wishful thinking went, there must be people within the organisations at the heart of that closed stagnating system who wanted progressive reform?

And how right they were.

*********

Readers of this blog will know that just because an author is compared in back-cover blurb to John Le Carré, it doesn’t mean that much. Such is the lazy reviewer’s short-hand for saying that a book is a good spy-related thriller. And of course, publishers use the accolade with alacrity. Only a few come close in quality and, more significantly, style to Le Carré. Handily, one of those few also achieves the far from simple feat of having a surname that rhymes with Le Carré; namely, Charles McCarry.

The front cover of my sticker-bespattered paperback copy of The Sixth Directorate (Coronet, 1977) carries a quote from McCarry.

‘Fast, sophisticated, splendidly authentic. Joseph Hone writes like an angel about devil’s work.’

The aforementioned back-cover blurb talks of a ‘thinking man’s thriller … with echoes of writers like Greene and Le Carré’. And to build up Hone’s reputation further, the obituary noted above quotes one of Britain’s leading contemporary novelists, William Boyd, crediting Joseph Hone as an influence on his own writing. In Boyd’s words, Hone was the author of ‘first-class works of fiction – as dark and well-researched as Le Carré’.

Hone was then a notch or two above your standard spy thriller writer — classy, complex plotting, original and literate; even if not quite a McCarry, Littell, or Le Carré. His novels were published in multiple editions, and revived (with foreword from espionage author Jeremy Duns) by Faber publishers in 2014.

Reviewing The Sixth Directorate, this Russia-in-fiction post alights on two particular aspects: the novel’s insights into the Soviet Union’s political future, and the detail of those few chapters set in Russia. Both of these aspects come from the early set-up chapters, before the action switches focus to the activities of Hone’s regular hero, Peter Marlow, in London and New York and the English Cotswolds.

The starting premise of The Sixth Directorate, published in 1975, was that there existed within the KGB a ‘clandestine Directorate’,

the nucleus of an alternative KGB, and therefore, potentially, of alternative government in the Soviet Union … politically orientated towards democratic rather than dictatorial socialiam … ‘Communism with a human face’, as the journalists had it

…

in the direction of a more human brand of Marxism, towards one of its happier variants

…

a flower that had bloomed ferociously in secret

The sixth directorate, p. 5

As the novel posits, such a socialist vision had by no means died out amongst Soviet citizens, even —quietly— within a minority of their leaders, in the 1970s. Reference is made to

Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia twelve years later

The sixth directorate, p. 5

In both of those examples, reformist Communist leaders had sought a less dictatorial Communism, and on both occasions the Soviet leadership had sent the tanks in and crushed such ambitions.

Hungary 1956

Prague 1968

The idea that inside the institutions of the Soviet system in Moscow, even in the KGB itself, were men who in their hearts wanted a more open and humane system, does not appear to have been widely held. But neither was it, of course, a unique notion set forth in Joseph Hone’s novel alone.

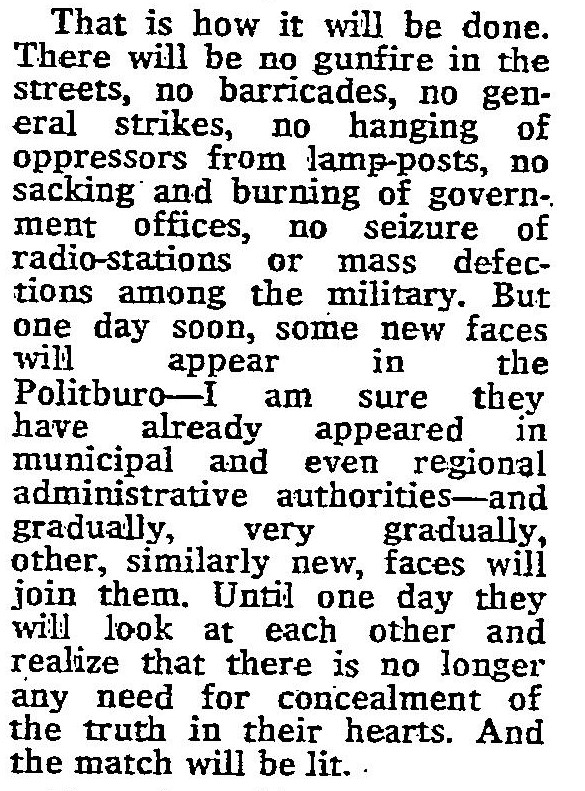

A couple of years after the publication of The Sixth Directorate, The Times columnist Bernard Levin penned a remarkably prescient series of comment pieces in which he argued that within the Soviet system itself existed those who were

in every respect model Soviet functionaries. Or rather in every respect but one: they have admitted the truth about their country to themselves, and have vowed, also to themselves, to do something about it

…

And if you tell me that no such figures exist in the Soviet Union, even more completely unknown outside (or for that matter inside) than the Czech heroes were, I shall tell you in return that it simply cannot be so … They are there, all right, at this very moment, obeying orders, doing their duty, taking the official line against dissidents not only in public but in private. They do not conspire, they are not in touch with Western intelligence agencies, they commit no sabotage.

bernard levin, The Times, 5 August 1977, p. 12

It is remarkable now to read Levin’s words from 1977 and insert the name of Mikhail Gorbachev and other reformers like him into the scenario he presents. Gorbachev and others were working their way up the Party ranks, doing their duty, serving the Soviet system, but intent on reform. Gorbachev himself was influenced profoundly by the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia in 1968.

And if you fancy blowing your mind a little at the prescience of these forecasts. Levin even cites a date by which these things will come to pass. Namely 1989. The year that saw Communist regimes fall in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and other Eastern European countries. The year that saw Gorbachev’s reforms within the Soviet Union itself bring democratic elections for the first time.

Joseph Hone based The Sixth Directorate, written a couple of years before Levin’s remarkable forecasts, on this notion of a quiet but determined reformist cadre sitting in the USSR’s central institutions; in this case, the KGB. His plot has the group as an organised and identifiable secret organisation, whose existence becomes known to those at the top. The KGB top brass set out to thwart this ‘Sixth Directorate’, whilst MI6 seek to preserve it.

To finish lauding The Sixth Directorate from the Russia-in-fiction angle —and good though this aspect is, it is only a small part of the novel— the opening two chapters are told with Yurii Andropov as their central figure. Hone was writing almost a decade before Andropov rose to the very top to become leader of the Soviet Union (November 1982 – February 1984). At the time that Hone was writing, Andropov was head of the KGB. Before that he had been Soviet ambassador in Hungary in 1956 when Moscow sent the tanks in.

Joseph Hone is pretty good on the detail of the mid-1970s. Whilst not much of The Sixth Directorate is actually set in Russia, the novel begins in Moscow. More specifically, it is set in the Rossiya Hotel, a huge place, the size of a city block, with 3000 rooms and miles of corridors, situated almost on Red Square. (It was demolished in 2006; and I miss it.) As the story begins, Andropov and his family (in this case fictional, since little was publically known about his real family at the time) are watching a show by Soviet comedian Arkady Raikin.

The Rossiya Hotel

Arkady Raikin

The first chapter of The Sixth Directorate is one of my favourite Russia-in-fiction thriller chapters. Though this is a category only just concocted for the purpose of this review, and so few other contenders come immediately to mind …