Gillian Slovo’s novel begins and ends in ice. Set in Leningrad, Ice Road follows about half a dozen characters through the decade from the early 1930s to the early 1940s.

Leningrad’s headline story over that period sees the death of one —Sergei Kirov, the city’s Party Leader assassinated in 1934—, followed by the deaths of many in the gathering brutality of Stalin’s purges, before unfurling to the prospective death of all in the genocidal 872 day Siege of Leningrad by the forces of Nazi Germany (1941-1944).

Readers who know even the outline of the Soviet Union’s path are aware of what is coming in the historical narrative as the novel progresses. Less evident, and —to Gillian Slovo’s credit— far less predictable than might be imagined, are the paths of her characters’ lives as they plot their courses through these times.

Ice Road begins and ends in ice. As the novel’s characters interact with actual historical events, we begin with a humble cleaning woman, Ira.

By dint of working in the Smol’ny Institute, the Leningrad headquarters of the ruling Communist Party, Ira gets volunteered to join the crew of the steamship Chelyuskin on its ill-fated voyage to prove that the Arctic route from European Russia to Vladivostok could be sailed in one summer run before the sea froze over again.

The Chelyuskin set sail from Murmansk in early August 1933, began to be caught in ice fields by the end of September, and eventually the ice tightened its constricting hold until it steadily crushed the ship to destruction in February 1934. Its crew escaped onto the ice, where they survived before being airlifted to safety in April 1934, in an operation that was celebrated by the Soviet media. Ice Road portrays this real-life event through the eyes both of Ira, serving on the stricken vessel, and of those back home in Leningrad, following developments through the regular news updates.

The Ice Road’s opening chapters provide a rich allegorical seam to be mined in what follows. The ice crushes the life out of the Chelyuskin and the optimistic intent of its expedition. Yet at the same time, from the frozen tragedy emerges the heroism of the crew; and salvation eventually arrives as they are transported away from their seemingly hopeless fate.

At novel’s end, characters whose lives we have followed over 500 pages and almost a decade of purges and war, are trapped in frozen Leningrad, besieged by Hitler’s army, afflicted by cold and hunger. From the air comes not salvation, but bombs. And it is the ice road, the lone siege-alleviating transport route across a frozen Lake Ladoga, that becomes the road of life.

Ice Road begins and ends in ice.

Ice Road has its smattering of real-life characters, the most prominent being Sergei Kirov; but its central cast of fictional figures represent different types.

We have already met Ira, whose first person narrative surfaces periodically in those chapters telling her story. Ira is the simple working woman, for whom the arrival of the Communist regime brought a form of liberation —from illiteracy, from a violent husband, from a predictable downtrodden life. She cleans the Party offices, travels on the Chelyuskin, and then later goes to work as housekeeper for Anton Antonovich.

Anton Antonovich is a member of one of the most dangerous professions in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. He is a Professor, and a Professor of History at that. Faced with the largely unspoken but ever clearer requirement to write in line with the emergent Stalinist orthodoxy, Anton Antonovich fears to keep writing about his favoured topic, the French Revolution, in case he draws the wrong conclusions. To write the wrong history would mean at best dismissal from his post; at worst, and more likely, arrest and execution. So he hits on the less dangerous idea of inventing an archival document —a medieval manuscript from Georgia, Stalin’s homeland— that can be made to say whatever fits the official line.

Anton Antonovich’s good friend, Boris Aleksandrovich Ivanov, is a senior Communist official in Leningrad —but not so senior that he doesn’t himself have to watch his back and keep in line with the higher-ups.

Boris’s daughter, Natasha, is the stand-out character in Ice Road’s cast list. She comes of age in the period covered by the book, marrying simple, joyful, loyal and kind Kolya, by whom she has a daughter. But this is Leningrad in the 1930s and early 1940s— the death of one is followed by the death of many and spreads towards the death of all.

Out of the blue, Kolya is arrested, accused of everything and nothing in that brutal ‘confess, we know you are guilty’ approach of the Stalinist security services, and executed.

‘I am not your comrade, you stinking piece of carrion, you heap of human excrement, can’t you even understand that? I am not your comrade … I am not even interested in you. All I want is for you to answer my question … now, not in five minutes, not in a day, nor in a month, although make no mistake about it, you’re not going anywhere, we can sit here for as long as it takes, you swine, you pygmy, tell me.’

These words resound, swine, dregs, pygmy, and more to come, you snot-nose, you filthy lickspittle, you, you scoundrel, countless others roaring through his head, the interrogator going at Kolya, dissatisfied with everything that Kolya tries to say, interrupting until he ties up Kolya’s tongue in knots, and then, demanding to know why Kolya is being so stubbornly silent, pleading sometimes and hectoring at others, telling Kolya to imagine the charge against him but Kolya can’t, he truly can’t, his strengths are practical, not within the realms of the imagination, he has always left that to Natasha.

Ice Road, p. 281

Widowed at the hands of the Soviet state, Natasha later remarries. Her second husband being a cold, unfeeling, Communist official, Dimitry Federovich. It is a marriage of grief-stained necessity that allows Natasha and her daughter to live in the manner to which they are used. It is not, however, a marriage of love or passion; for these, Natasha must recklessly depend on a furtive but fervent love affair with the American, Jack Brandon. And the more Natasha is risking everything to be with Jack, the clearer her feelings for Dmitry become.

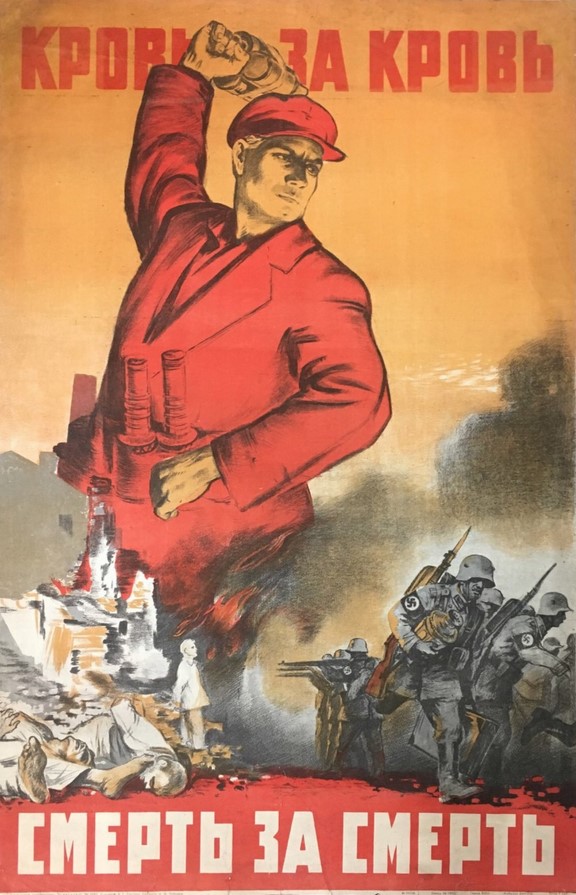

She hates him, when, that is, she has the strength to summon up her hatred.

Her hatred is irrational … Nevertheless she hates him. She hates him for … For everything he represents. For being alive when Kolya is dead. For being there when Jack is gone. She hates that twisted smile of his, that unchanging plainsong of his instruction which is his only form of conversation and she also hates his silence. She hates him. Full stop. She is consumed by her hatred, as if that slogan: Death for death. Blood for blood … that is everywhere in Leningrad has wormed its way inside of her, turning her detestation of her husband into something live. She hates the Germans, yes, of course she does, for everthing they have done and everything they want to do, but on top of that she hates an individual. She hates Dmitry Fedorovich. She. Hates. Him.

Ice Road, p. 477

Ice Road’s depiction of the lives of its various individuals reads to some extent like reportage, as if taken from observation or diary entries. Gillian Slovo does not corral her characters too obviously into a plot-bearing artifice. Her writing is more naturalistic than that. Figures come to the fore of the novel and retreat into the background as would happen over a period of years. They step in and out of each others’ lives; sometimes in lengthy narrative chapters, at other times in short chapters of a few paragraphs. Presenting their different perspectives works against a simple hero/villain categorisation. And their actions are not as predictable as Russia in Fiction imagined they might be.

From the Russia in Fiction perspective, Ice Road deftly draws the reader into its world, intertwining the historical events of those pitiless years with the lived experience of its range of characters.

Ice Road begins and ends in ice; but its humanity keeps burning throughout, letting the reader into the lives of a group of friends and colleagues and acquaintances whose life spans collided head on with those extraordinary years blighted by totalitarian brutality.