Part one of this review is here

War in Afghanistan. The Soviet Union learnt a couple of decades before the United States that however super the superpower, its military might does not guarantee an easy victory when such a war turns to guerilla engagement in barren mountains and ambush-friendly valleys.

In The Hour of the Lily, John Kruse explored, through the lens of fiction, this clash between the armed forces of the Soviet Union and the guerilla units defending their homeland and culture. The geographical setting throughout is Afghanistan. The temporal setting is 1982, as the Soviet occupation forces have ensconced themselves in Kabul and are beginning their ultimately fruitless task of trying to quell mujahideen opposition.

Kruse is an accomplished writer who has done his research. The terrain of Afghanistan, the sights and sounds of Kabul, the socio-cultural aspects of a tribal system within a strict Islamic setting; all these and more are well drawn.

Plot-wise, the set-up is that Pola, the estranged wife of Soviet GRU (military intelligence) Colonel Andrei Pavlovich Yakushev, falls in love with resistance leader Khan whilst working in his remote mountain village as a Soviet educator. The Soviet versus mujahideen conflict then becomes, for the purposes of the narrative, encapsulated in the personal conflict between Yakushev and Khan, with Pola far from a by-stander.

The only western involvement comes midway through, when celebrated press photographer, McCabe, arrives, with covert CIA assistance, to publicise the Soviet atrocities that he believes to be occurring— specifically the use of chemical weapons. Over 400+ pages and several months the plot develops, as the Soviet armed forces plan a major offensive and the mujahideen seek to disrupt and counter it.

In terms of how Russia/the Soviet Union is presented in The Hour of the Lily, Kruse identifies many of the elements of the Soviet military campaign that would later be critiqued and evidenced by military and academic analysts. The attempt by McCabe to prove that the Red Army used chemical weapons against the Afghan resistance is one such element that is to the fore.

There is also a brutal scene of mass rape by Soviet soldiers against Afghan women, the punitive massacre of Afghan civilians, tensions between the occupying Soviet authorities and their supposed allies in the Afghan secret police (the Khad), and difficulties in ensuring the loyalty of the many Muslim soldiers from the southern republics within the conscripted ranks of the Soviet army. This latter element became an increasing concern for Soviet military men and political leaders alike as the 1980s progressed.

The battle scenes likewise highlight the common criticism of Soviet tactics — that the military and its leadership had for years prepared for tank battles against NATO on the wide plains of central Europe, and were unable to adapt to guerilla fighting in the narrow gorges of Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain. Though of course tactical inflexibility was to a large extent made up for by overwhelming technical superiority. However poor the tactics, helicopter gunships, air superiority, and massive ordnance would inevitably have their effect against the less technologically advanced mujahideen fighters when they actually met in combat.

The opening chapter of The Hour of the Lily is similar to the opening chapter of Russian Spring (1984) by Dennis Jones. Both these thrillers begin in a village in the mountains of Afghanistan, as Soviet troops engage with ‘rebel fighters’ and their families.

Overall, The Hour of the Lily is worth the perseverence. Its story builds slowly, and its climactic battle pulls the multiple threads together. The novel’s main attraction comes though in the rare insight it provides, from the Russia-in-fiction perspective, into a too often forgotten war.

It was not really until the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, as the Soviet Union collapsed, that open public discussion of the realities of the war began to happen in Russia. Indeed, one of the most significant works in that respect, written by a journalist, Artyom Borovik, who had witnessed the conflict first hand, bore the title Спрятанная война (The Hidden War) and was published in English in 1990 and Russian in 1992.

The Soviet-Afghan War was a big deal not just for its combatants, but for international and Soviet domestic politics.

Internationally, Soviet intervention in Afghanistan prompted the US boycott of the Moscow Olympics in 1980, but also —and far more seriously— it gave further fuel to the conviction amongst Western leaders that the USSR was an expansionist ‘evil empire’ ready to assert military superiority to achieve its aim of global Communism.

(I vividly recall, as an impressionistic teenager becoming aware of global affairs, feeling a jolt of shock and fear when listening to the radio on Christmas Eve 1979 and hearing the news on BBC radio that Soviet forces had invaded Afghanistan.)

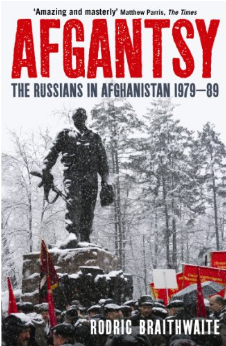

The invasion fired the starting gun in a ratcheting up of East-West tension that was to bring the world to the brink of nuclear conflict over the next few years. Taylor Downing’s 2018 book 1983: The World at the Brink provides a fine account of how close this developing East-West tension came to fomenting nuclear armageddon. And for a fine English language book on the Soviet experience of war in Afghanistan, see Afgantsy (2011), by former British Ambassador to Moscow, Sir Rodric Braithwaite.

In the world of western popular culture, the Soviet-Afghan War features in the Tom Hanks movie Charlie Wilson’s War (2007) —based on the non-fiction book by George Crile Charlie Wilson’s War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History (2003) — and in the 1987 James Bond movie, The Living Daylights. The former is very much a US-based story, the latter is, well, a Bond movie.

Beyond, and even within, these examples, however, the Soviet-Afghan War of 1979-1989 is too little represented or known in terms of popular culture. Reading The Hour of the Lily puts that right. Or at least it would were John Kruse’s novel not so little known itself.

Part one of this review is here