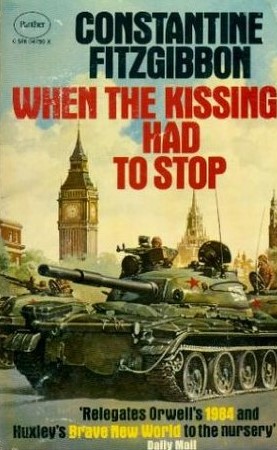

When the Kissing Had to Stop was a celebrated ‘coming threat’ thriller back in its day, that is just before the 1960s —the end of the Chatterley ban et cetera—got going.

From the Russia in Fiction perspective, this reasonably slim novel is worth a quick review simply because, as thrillers tend to do, it provides a useful caricaturish picture of popular conceptions of Russia. Specifically, When the Kissing Had to Stop offers a conservative, even establishment, portrayal of a Soviet Union taking over Britain with the same ruthlessness with which it had imposed its rule in Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War.

Like many such ‘Red threat to the UK’ novels (see our review of Russian Hide and Seek for a list), When the Kissing Had to Stop tells us more about England and about the author’s politics than it does about Russia.

Despite just qualifying for a 1960s publication date, When the Kissing Had to Stop was written in the 1950s and is very much of that decade. It is set in a Britain that has emerged out of the Second World War as a diminished power playing second fiddle to the United States in the emergent superpower stand-off. The Suez Crisis of 1956 is referenced in the narrative as an indicator that Britain can no longer intervene in world affairs with the self-assured leadership of earlier decades, and its ruling class act with a combination of necessary respect for, and innate condescension towards, the US.

Constantine Fitzgibbon himself had served both in the British and the US military in the Second World War.

He presents a set of characters predominantly from the upper classes and the establishment.

The milieu is country houses, restaurants on Charlotte Street, London clubs, servants and behaving properly. Attitudes are very much of that time before the rebelliousness of the 1960s. The place of women —in the view of Fitzgibbon’s male and female characters— is traditional. Even when their politics are more radical, Fitzgibbon’s women are never leaders, but lovers and homemakers and somehow in awe of the men. The class structure is taken for granted, as working people treat gentlemen and ladies as a separate group deserving special respect. Fitzgibbon’s England is a place threatened by Teddy Boys and racial tension, the latter stoked by immigration.

From today’s viewpoint, When the Kissing Had to Stop is a right-wing warning that Britain is on the way to terminal decline. And to push Britain over the edge, step forward a left-wing government brought to power on the back of an emotive campaign against nuclear weapons, and determined to see the removal of American bases from these islands. Standing ready to take decisive advantage of these ‘useful idiots’ is the Soviet Union, whose leaders have elaborate plans to turn Britain into a vassal state.

A common feature of ‘coming threat’ thrillers is their setting in the indeterminate near future; in other words, in a world very much like the present but just pushing current trends a little further.

(Whenever Russia in Fiction thinks of this near future setting, our mind goes to Henry Porter’s superb, but not Russia-related, The Dying Light (2009) —called The Bell Ringers (2010) in the US— with its elaboration of a coming surveillance society).

When the Kissing Had to Stop has Britain, the US and the USSR all governed by fictional characters. Even the British Head of State is referred to, without further detail, as ‘the monarch’; presumably Fitzgibbon was too much of traditional gentleman to portray Her Majesty the Queen in fiction.

And what about Russia? In the real world in 1959, Nikita Khrushchev was the leader of the Soviet Union. But in the near future, we are dealing with a Soviet leadership that has risen to the top ‘since the death of Khrushchev’ (Chapter 2).

The supreme master of the Soviet Union was a puffy-faced man of fifty-two, who had learned his Kremlin politics as assistant secretary to Josef Stalin. By the time that Khrushchev was no longer there, re-Stalinization had been in all essentials completed. Kyril Vassielivitch Kornoloff, had, however, symbolically reintroduced many of the forms that had prevailed in Stalin’s lifetime. One of these was to make his decisions very late at night, after a fairly heavy meal and copious glasses of Crimean champagne. Kornoloff had an extremely strong head. Some of his colleagues had not. This gave him an advantage. He never missed taking an advantage.

When the Kissing Had to Stop, chapter 2

Fitzgibbon takes us to the Gulag in Arctic Russia, to the ‘Foreigners’ Hut of Block C, Sub-Camp 17, Labour Camp Novaia Zemlia’, where international prisoners are held and worked to death under the harsh supervision of a German prisoner trusted by the guards.

The Soviet leadership bide their time to install their chosen person in number 10 Downing Street. And when that time comes, the serving British Prime Minister is invited to Moscow, where he dies at a Kremlin reception of an apparent heart attack, caused by poisoning his drink.

As the coup in London takes place, KGB techniques are deployed as potential oppositionists are arrested in one night and either placed in holding camps, or tortured and executed. Soviet military forces come to Britain initially in the guise of a ‘Russian Inspectorate’ arriving to confirm the dismantling of nuclear weapons.

And in the novel’s Epilogue, the details of the Soviet Union’s mopping up operation to strengthen its hold over Britain are set out, with the help of reference to the great ‘virgin lands’ campaign that Khrushchev had launched at the time of the novel’s writing.

Since it was clearly illogical to attempt to feed fifty millions of people on an island designed for less than half that number, the Soviet Union had graciously decided to make available large areas of rich virgin land in southern Siberia to which a portion of the British population would be transferred. This ‘grandiose act of far-sighted social engineering’ would solve once and for all Britain’s export problems.

Constantine Fitzgibbon’s knowledge of Russia is not impressive. He has Christmas Eve being celebrated in Moscow by ‘small congregations, mostly women or men of more than sixty years, who were making their way to the occasional dilapidated, musty churches’. OK, but Fitzgibbon makes this happen on 24 December, rather than on the correct Russian Orthodox date of 6 January.

He makes passing reference too to the somewhat clichéd Russian description of England as ‘foggy Albion’ (туманный альбион).

This is a phrase that Russia in Fiction first came across one day in the early 1990s; accosted by a chatty Russian on the Moscow metro, I puzzled over what on earth he was talking about, not realising how common this description of England, of London in particular, was amongst educated Soviet citizens.

The elucidation of the phrase is adroitly deployed by Constantine Fitzgibbon to encapsulate the dangers that he saw as facing Britain, and its élite, as the 1950s drew to a close. As a Soviet officer explains to one of his colleagues:

‘You were no doubt brought up to believe that this city of London was lost in a perpetual fog. That is no longer true. But the fog persists in their minds … Foggy minds have led them this far. Let the fog thicken. We can only gain by it. History is on our side, and our task is in reality only to give it a helping hand.’

When the Kissing Had To Stop, Chapter 11