A beautifully written allegorical fantasy in novella form, Glen Hirshberg takes Thomas, a middle-aged German on the cusp of fatherhood, on a short trip back to the city where he spent his wilder younger student days in the early 1990s. That city is St Petersburg. A city that itself has changed from those wilder days into a far more settled state.

So Freedom is Space for the Spirit is an allegory of life stages, looking back to the open fields of youth as the responsibility of parenthood approaches? And of the new Russia beginning to establish itself more securely after its chaotic early years?

May be so.

A beautifully written allegorical fantasy in novella form, Glen Hirshberg portrays contemporary St Petersburg, recognisable except for one aspect – amongst the people, ignored and almost unnoticed, roam bears. Actual bears, with fur, claws, and all; but without mouths.

So Freedom is Space for the Spirit is an allegory of Russia? Of the Russian bear, having lost its voice? Or been rendered toothless? Or of Old Russia fading into the background of contemporary urban globalised Russia?

May be so.

A beautifully written allegorical fantasy in novella form, Glen Hirshberg has a wild Russian artist-cum-‘holy fool’, Vasily, move out to the East, to the taiga, for years, to live in ‘real’ mystical Russia. He then returns to St Petersburg, summoning his old friend Thomas from the West and Ana, a young Petersburg-dwelling woman who is also his niece, out of the city to enthuse them about the ancient spiritual Shamanic ways he had learnt.

So Freedom is Space for the Spirit is an allegory of Westernisers and Slavophiles? Of materialism versus spirituality?

May be so.

And may be all of the above. And more.

Whatever the allegorical messaging, Freedom is Space for the Spirit delights in description. Glen Hirshberg is an American author, whose usual genre is horror. Russia in Fiction cannot find an immediate Russian connection in his biography, but he writes about Thomas’s student days in early 1990s St Petersburg with at the very least a sense of the abandon of that era, then multiplied in combination with the freedoms of young adulthood.

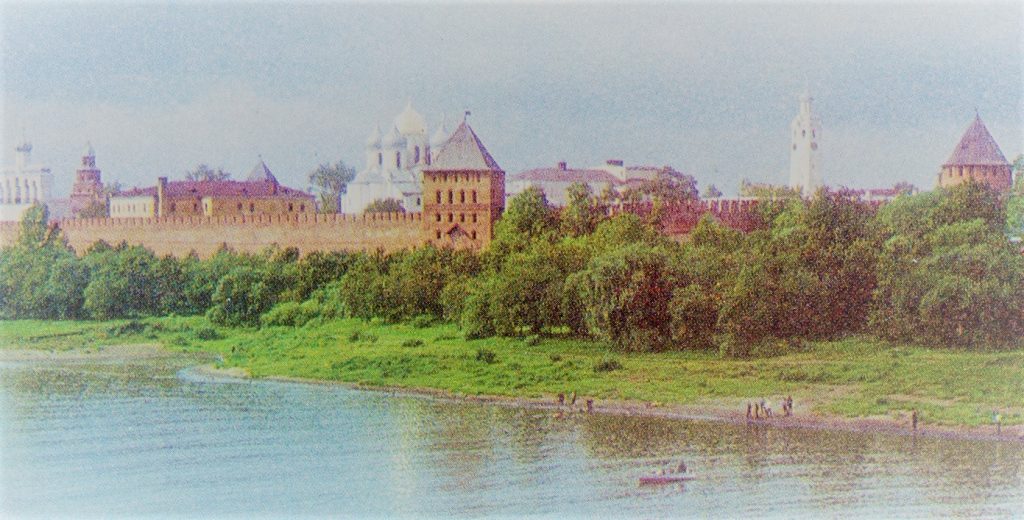

For nearly a year, they’d wallpapered windowless squatters’ digs with daisies in abandoned St. Petersburg buildings and left them for no one to find; put on silent concerts, lip-synching and gyrating, in the middle of parks in the middle of the night; rowed a convoy of johnboats festooned with homemade Big Mac wrappers down the Volkhov, under the pedestrian bridge into the thousand-year-old heart of the Novgorod Kremlin, and then set the boats on fire as the waiting militsiya closed around and finally arrested them

When he revisits, a quarter of a century later, Thomas knows the temporary but transporting awe of return as he arrives into St. Petersburg’s Vitebsk station.

Here! Instantly, his gloom lifted like something he’d dreamed (this the reality, this his world, where he most belonged). Stumbling over his untied shoes in his excitement, Thomas exited the cabin … to emerge at last into the Vitebsk main hall. For a while, he just stood on those palatial stairs, staring up into the domed iron ceiling, his hand on the chipped marble of the banister, listening to the snarl of this least Russian of Russian cities sweeping across the grand checkerboard tile to greet him.

Beautiful stuff.

There is then something almost Gogolian about the sudden appearance of the absurd amidst the normality; in the form of mouthless bears, roaming around the busy city, largely ignored, climbing on and off trams and buses, unmolesting and unmolested. According to a newspaper article that Thomas comes across, the bears had been around for a few weeks. At first the politsiya had tried to round them up, but soon stopped. After all, the bears were causing no problems.

In the end —and please don’t complain of spoilers in regard to a fantasy novella— it turns out that the bears are the students of his old artist friend Vasily, who appears to have used a shamanic ceremony to turn them into bears. Only, in true chaotic Vasily fashion, he has not quite perfected it, and did not intend his bears to have no mouths.

Glen Hirshberg himself circles around nailing down any allegorical meaning. Which is how it should be.

The newspaper article that Thomas reads has a go.

“A work of art?” the article’s author postulated. “The Great Bear of Russia gone toothless and old, or wild and free, or gentle and loving to its own people at last? The shambling emblem of a Russia that even Russians have long ceased to dream?”

And Vasily, the man behind the bears’ appearance, intended them as a gift

… to poor, confused, mafia-infested, Starbucks-infested, Putinized, brutalized, baffled, beautiful St. Petersburg: a memory from an even more savage, beautiful time we’ve all forgotten, or denied, or repressed, or dreamed. A kiss —my kiss— to the northernmost city in the world, from the far East they’ve forgotten is even there.

Freedom is Space for the Spirit is a gift in itself; slight in pages, it is an affecting and memorable novella, whose emblematic Russian bears stay in the memory. And the novella’s end catches the breath and moves the heart.

Freedom is Space for the Spirit more than repays the small price in time and money that it takes to read. What are you waiting for?

(And thanks are due to the excellent Russia Reviewed blog, whose review of Freedom is Space for the Spirit, back in April 2017, first alerted us to this fine work.)