Brian Garfield’s thriller Kolchak’s Gold takes on the mystery of what happened to the gold reserves of the Russian Empire after the revolution of 1917.

This is a made-for-fiction mystery. It is known that the gold —which had been transported to Siberia from St Petersburg during World War One to prevent it from falling into enemy hands— came under the control of the overall leader of the White movement in the Russian Civil War, Admiral Aleksander Kolchak.

After Kolchak was captured and executed by the Communists in 1920, a significant portion of the Imperial gold was not found; and significant means billions of dollars worth

.

Kolchak’s Gold tells the tale of Harry Bristow, an American historian of Russia, whose research sets him on the trail of the missing gold. Unfortunately for Bristow, and unknown to him, his success in following the archival clues to the gold’s whereabouts owes a good deal to the security services of the USA and Israel stoking his interest and opening doors for him.

By the time —after painstaking research in the Soviet archives in Sevastopol, Crimea— Bristow solves the mystery of what happened to the Imperial gold, his unwitting links with US intelligence mean that the KGB are poised to arrest and interrogate him, and the US and Israeli security agencies want to cash in on their unasked for sponsorship of Bristow’s endeavours by extracting the intelligence he has procured.

Bristow, being an archetypal independent-minded hero who does not take kindly to being manipulated, is unwilling to cooperate. Cue a tense manhunt through the southern Soviet Union, specifically Crimea and Georgia.

Brian Garfield (1939-2018) was a prolific author, penning over 70 books; the best known of which was Death Wish, which became a hit movie starring Charles Bronson. Garfield wrote two Russia-related novels: Kolchak’s Gold (1973) and The Romanov Succession (1974).

Russia in Fiction has not read The Romanov Succession, but the cover blurb and historical disclaimer from its e-book re-publication in 2014 suggest that it is an ‘assassinate Stalin and replace him with a Romanov pretender’ speculation.

Settling down to read Kolchak’s Gold, it is immediately apparent that we are in the hands of an experienced and accomplished writer of popular fiction. The novel is constructed so as to establish from the opening pages that its hero, Harry Bristow, is a man on the run and fearing for his life; ‘the quarry of a ludicrous number of security agencies’ because of what he has discovered during his research in the Soviet Union.

The first chapter, distinguished from the rest by the use of typewriter font, is in the form of a letter from Bristow to his publisher, explaining that the scribbled notes and typed fragments on hotel stationery that have arrived in the mail represent a very rough draft of a manuscript that can be supplemented by other material in a folder marked ‘Kolchak’ in his office filing cabinet.

I’m leaving it to you and the McKay editors to select a title; to arrange the organization of chapters and whatnot; to rewrite and add explanatory notes wherever they seem needed; and to find a sensible concluding wrap-up if circumstances don’t permit me to send you further material. There’s more, but I feel them breathing too close to me.

On the back of the explanation that the book in the reader’s hand is made up of a disparate set of document types, Kolchak’s Gold has chapters in different formats, the notes of its apparent editors frequently appear, and it is clear throughout that Bristow has still not reappeared in the States.

Such a fictional device allows Brian Garfield to make 50 of his novel’s 300+ pages a history of Admiral Kolchak’s role in the Russian Civil War — ‘Kolchak’s War … An incomplete manuscript from the New Jersey files of Harris Bristow’ (p. 47). The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk; Kolchak’s appointment at the head of the White forces with the vainglorious title ‘Supreme Ruler of All the Russias’; the story of the Czech Legion [see our review of The People’s Act of Love for the best novel centred on the Czech Legion]; the ebbing and flowing of White and Red victories in the brutal Civil War; fighting in Omsk; and finally Kolchak’s capture, questioning, and execution in Irkutsk.

Threaded throughout this account is the partly-fictionalised story of the train carrying the Imperial treasure, which Kolchak’s Gold finally places hidden in a disused iron mine in Siberia.

All of this set-up, whilst useful, is simply set-up. And for those who know their Russian history, these pages are skippable. Though Russia in Fiction is glad we didn’t skip them too readily, or we would have missed the acerbic aside that Garfield places in the mouth of one of his characters, who has witnessed appalling brutality during the Civil War. Referencing the academic debates about Russia that were prominent in the West in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he says

Our Captain at the time was a brute called Grigorenkov, a Muscovite … He cursed and kicked the subordinates there, myself included … Cringing and brutalizing are equal parts of the Russian character, I should say. We were always burdened with the kind of vermin who leap from your feet to your throat. Have you read Alexander Werth? He has the audacity to insist the Russians are a fundamentally unaggressive people!

Kolchak’s Gold, p. 58

Where Kolchak’s Gold comes to life is when it moves on from its lengthy set-up, to take Bristow to 1970s Sevastopol, on the Crimean coast. It is an unusual setting for a thriller, and whether Brian Garfield had visited there or not (our presumption is not), he draws well aspects of Soviet life.

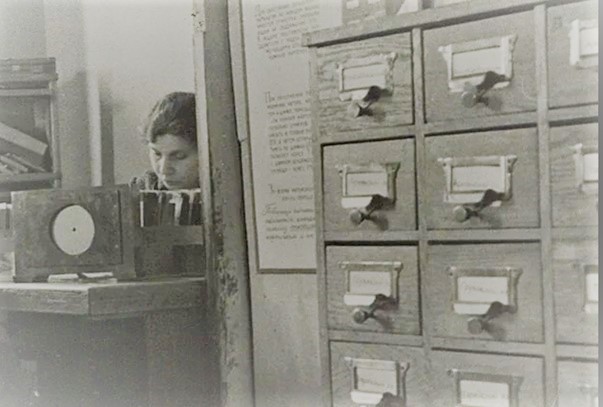

And of particular interest to Russian in Fiction, his descriptions of the work of a historian in the Soviet archives are expertly pitched — the card indexes, the forms to fill in, the archive attendants at their desk, as much guarding their material as facilitating its use. It is here that Bristow finds the evidence to show that the German army in World War II removed the gold westwards.

From here on in Kolchak’s Gold becomes a recognisable and well-written thriller, with the standard tropes expertly done and made original for most contemporary readers by the fact that they take place in the 1970s and in the southern Soviet Union, rather than in Moscow. Bristow learns to spot his KGB tails, and manages to shake them off on the streets of Sevastopol.

There are car chases, and false papers, and tense border crossings, and a strong love interest. The second half of Kolchak’s Gold is a different book from its first, and all the better for it.