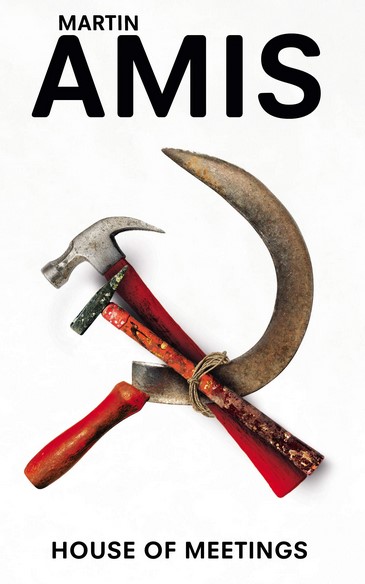

Predictable? That Russia in Fiction would follow a review of a Kingsley Amis novel with a review of a novel by his son Martin? May be so. But the authors’ shared surname is about all that these two books have in common.

Russian Hide and Seek (1980) was barely about Russia at all. House of Meetings essays a profound exploration of Russia; from the first page of Part One to the novel’s closing line.

This is a love story. All right, Russian love. But still love

******

Russia is dying. And I’m glad.

House of Meetings, p. 7 and p. 196

House of Meetings might start off proclaiming itself to be a love story —albeit ‘Russian love’— but it is a cleverly crafted and slickly phrased meditation on some of the darker aspects of Russian history.

Its unnamed Russian narrator —setting out his story as a last testament written to his thoroughly contemporary American step-daughter— is a former inmate of the Soviet Union’s forced labour camps in the 1940s and 1950s, en route in 2004 to re-visit their Arctic sites by means of a ‘Gulag tour’.

(And if you think that such a trip is mere narrative device, think again. Russia in Fiction has just looked up the availability of a similar itinerary on the excellent GoRussia website. Krasnoyarsk to Dudinka in 2022. 11 days. On the ‘elegant and modern’ 5 star ship, Maxim Gorky. Prices starting around £7k.)

In House of Meetings the first person narrator travels by luxury tourist steamer, the Georgi [sic] Zhukov. The horrors of the Beslan school siege atrocity play out on the TV news as the journey progresses towards the Arctic port of Dudinka in Russia’s frozen north.

This is an artifice very similar to that used by Malcolm Bradbury in To the Hermitage (2000), where the armed conflict between Russia’s parliament and president in 1993 similarly plays out on the TV news as the novel’s central character sails towards St Petersburg.

The narrator of House of Meetings describes, in deliberatively couched detail, the brutality that he has seen, serving in the Soviet armed forces under Georgii Zhukov in World War Two and serving his sentence in the Gulag in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

He confesses too his own participation in violence, both in wartime, and during the fighting between inmates in the camps.

in the first three months of 1945, I raped my way across what would soon be East Germany

******

Lev once saw me fresh from a killing; my second … badged with blood, and panting like a dog that has run all day

House of Meetings, p. 26 and p. 85

House of Meetings strives artfully and unflinchingly to portray the psyche of its chronicler amidst the elemental cruelty and violence of global conflict and Stalinist repression as he deploys visceral vocabulary to write to a young 21st century American woman, his step-daughter Venus, ‘with your good diet, your lavish health insurance, your two degrees, your languages, your property, and your capital’ (p. 196).

The description of the Arctic Gulag camps in 1948 exemplify Amis’s style

a time of spasm savagery … The factions had, at their disposal, a toolshop each … warm work with the spanner and the pliers, the handspike and the crowbar, vicings, awlings, lathings, manic jackhammerings, atrocious chisellings.

House of Meetings, pp. 20-21

As is our wont, Russia in Fiction will spare the details of castrations and blinding, of ear perforations and hand-losing frostbite. They and more of the same are there for you to read in this slim, admirable, and powerful novel.

Martin Amis had come to writing House of Meetings shortly after the publication of his non-fiction account of Stalinist terror Koba the Dread (2002).

And whilst his subject is primarily the paroxysms of violence that scarred Europe, and Russia in particular, in the mid-twentieth century, Amis goes out of his way to show, and indeed explicitly state, that what he is writing about cannot be confined to that era, and that manifestation of the Soviet state, alone.

Russia is the nightmare country. And always the compound nightmare.

House of Meetings, p. 196

The Beslan school siege of 2004 —in which 333 people, including 186 school children, were killed— is depicted as an ongoing news event during the narrator’s journey north. An account is also given of the Moscow theatre siege of 2002, which saw at least 170 die.

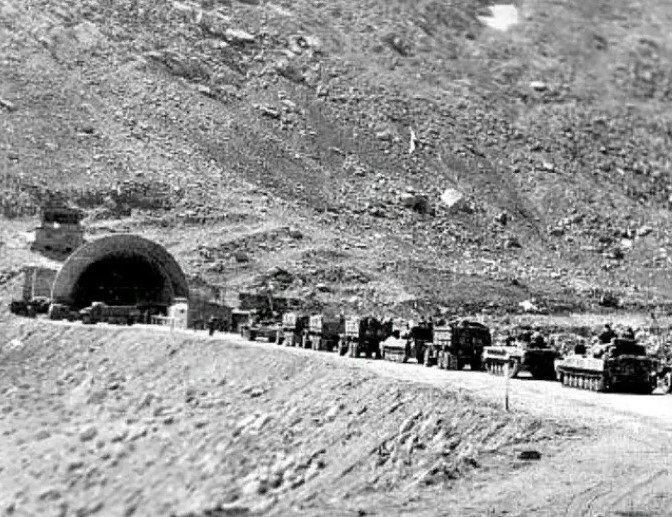

There is a description too of one of the most horrifying events of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, the Salang tunnel fire of 1982, in which a similar number died.

And when we say description, we don’t mean some journalistic-style account. The narrator of House of Meetings wants to emphasise the horror of those deaths

Blinded, maddened, choking, groping, flailing, pounding – and slow. A total death, a deep death.

House of Meetings, p. 140

No, it is not just the darkest history of the Stalinist era that the narrator of House of Meetings condemns. This is a story decorated too with contemporary social data, from the middle of our century’s first decade, on abortions, death rates (rising), birth rates (falling), and syphilis amongst teenage Russian girls.

And in its first chapter the target of the fictional memoirist’s ire is explicitly set out. And it is broader than Stalinism, broader than Putinism and post-Soviet collapse.

Oh, and just to get this out of the way. It’s not the USSR I don’t like. What I don’t like is the northern Eurasian plain. I don’t like the ‘directed democracy’, and I don’t like Soviet power, and I don’t like the tsars, and I don’t like the Mongol overlords, and I don’t like the theocratic dynasts of old Moscow and old Kiev. And I don’t like the multi-ethnic, twelve-time-zone land empire. I don’t like the northern Eurasian plain.

House of Meetings, p. 12

One of two standard questions addressed by Russia in Fiction reviews is, how is Russia portrayed? So far, so unremittingly grim. War, rape, forced labour, brutally portrayed violence, terrorism. And we have not yet even mentioned the theme of Russian anti-semitism that runs like a thread through House of Meetings.

But what about our other standard question, the novel as story?

House of Meetings revolves around the relationship between its narrator, his younger step-brother Lev, and the beautiful Zoya, whom both brothers love.

The narrator reveals himself as a participant in the horrors through which he lived, whilst at the same time seeking to show that the elemental violence of that time pushed him in this direction. His account reads as an attempt to explain, indeed justify, himself to his much loved American step-daughter. If only she could know what it had been like.

It would suit me very much if, at this point, I could easternise your Western eyes, your Western heart.

House of Meetings, p.27

But Amis is too skilled a novelist to leave the single voice to stand unchallenged. The trouble with the narrator’s exculpatory account is that his younger brother, Lev, lived in the camp alongside him but clung to a pacifist, non-violent stance, however much he suffered for it.

The narrator’s capacity for violence is put forward within the self-justificatory context of war, imprisonment, and the fight for survival. ‘Venus’, he addresses his step-daughter, ‘the peer group can make people do anything. And do it day in and day out’ (p. 27).

In the camps, if you want to survive, you fight, you steal, you inform, you kill, and in doing so you ‘sometimes shortened lives that were already ruined … The camp was more war, Venus, more war’ (pp. 86-87).

And yet, little brother Lev refuses to act in this way. He is a ‘conscientious objector’ in the war that is camp life. After he has been in the same camp as the narrator for a week, Lev is still sleeping on the floor, and his brother urges him to fight for a bunk, to pick on a weak person with low rations, and to literally and figuratively drag him down. ‘By what right?’ is Lev’s response.

Their relationship with Zoya encapsulates this difference between Lev and his brother. The narrator, the older brother, is smitten with Zoya, when he meets her in Moscow in 1946. Fresh from the war, he is used to having women either by force or —back home in Russia— at least in unthinking and carelessly manipulative and casual ways. But Zoya is different. They become friends, he is entranced, but then comes arrest and he ends up in an Arctic labour camp.

Two years later, Lev also turns up in the camp. And to his brother’s fury, he reveals that he has married Zoya. As the novel progresses, it is clear that Lev’s secret to winning Zoya —if that is what it is— is simply, but counter-culturally, to be gentle and kind.

Zoya is

unusually attractive … in January 1946 she was like a rebuke to the prevailing conditions … like an act of civil disobedience. She was recklessly conspicuous … Perhaps the single most unbelievably wonderful thing about her was that she had her own place … with its own stairs and its own front door.

House of Meetings, pp. 28-29

She also has a series of lovers; with the connection between promiscuity and property seeming clear.

Yet amidst the Stalinist whirlwind, Zoya finds that Lev offers calm and kindness. In contrast to the violent sexual nature of the narrator (‘the first thought I was used to – some variant of When can I wrench her clothes off?’), the love-making of Zoya and Lev is described as lasting for hours, even days.

In its final parts, House of Meetings moves on to life after the camps, and the ongoing inter-locking relationships between narrator and Zoya and Lev, exploring the lasting effects of their experiences.

This is a novel whose final half dozen words are ‘Russia is dying. And I’m glad.’ The reader could readily assume that —particularly given the House of Meetings’s relentless representation of brutality, dehumanisation, and decline— that the narrator is the authorial voice. May be so. But Lev stands alongside, preferring integrity even if he may be crushed. At novel’s end, it is his brutish older brother who is quite literally dying, and is glad to see the end of the Russia he has known.