Part one of this review is here

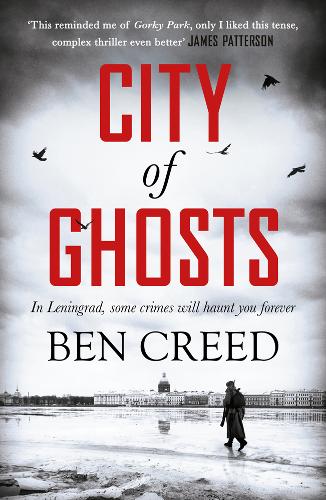

One winter night in 1951, several miles outside of Leningrad, five mutilated corpses are discovered, laid out —indeed positioned— on railway tracks. Leningrad police (militsiya) officer, Rev Rossel, conducts an investigation that increasingly ties the murders to his own previous life as a violin student in the Leningrad Conservatory.

City of Ghosts vibrates with dissonance between the ubiquitous and ingrained violence of late Stalin-era Leningrad and the transcendent potency of music. Alongside portrayals of savagery by state and criminals alike, Ben Creed conjures up the otherworldliness of music.

The novel has five parts, each designated by a musical note; a motif that reaches a crescendo by its end whilst having been a refrain throughout. F A E♭ B♭ G.

Rossel hummed the notes under his breath.

The refrain had dissonance at it heart, like a folk song from the Caucasus. Three of the notes formed the triad of E-flat major —a key associated with heroes. The F was the second note of that scale, the A natural was the odd one out —not part of the scale at all. From E-flat to A was a tritone, what composers three hundred years previously had termed a diabolus in musica. The devil’s interval.

City of Ghosts, chapter 30

Revol’s new neighbour, Tatiana Vasileyeva, presents a figure of beauty standing apart from the world of criminality, courseness, and cruelty in which he works. Their acquaintance is made as he hears her singing the lilting Cossack folk melody ‘Oy, to ne vecher’; a song that he associates with a carefree love affair of his youth.

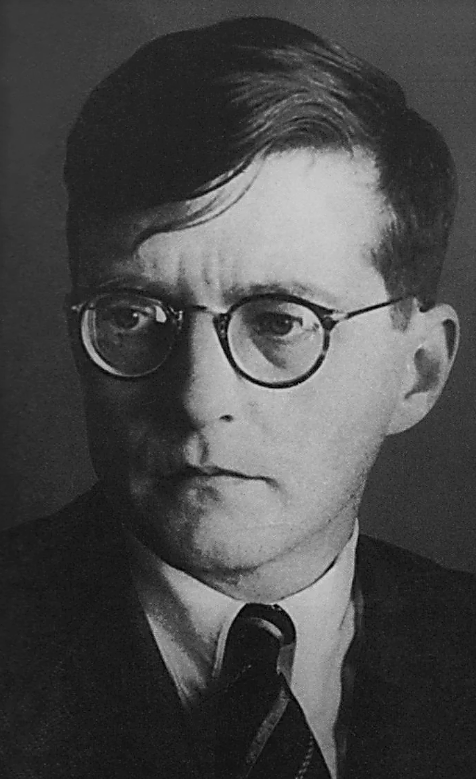

The dissonance of music comes too in the musicians in City of Ghosts. Creed creates a Soviet Salieri, consumed by envy for the genius that was Dmitrii Shostakovich.

The fictionalised story of Antonio Salieri, jealous inferior to his contemporary Mozart, is best known today through the movie version of Peter Shaffer’s wonderful play Amadeus. Less well known is that this depiction itself has Russian roots in Pushkin’s drama Mozart and Salieri (1832), turned into an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1897.

Creed’s Salieri is the fictional Nikolai Nikolayevich Vronsky.

‘Second only to Shostakovich in the great pantheon of twentieth-century Soviet composers,’ as Isvestia’s music critic had once called him.

City of Ghosts, chapter 13

The exuberant figure of Vronsky is of course no fan of his erstwhile rival. Rossel compliments Vronsky’s composition in honour of wartime Leningraders. The composer thanks him with a sought-after ticket for his up-coming premiere.

‘No one could feel and encompass their triumph in the great siege of the Hero City, like you have done, except Shostakovich himself.’ …

‘Very good, in fact. You are indeed the listener I have been looking for.’

The composer took a small piece of card from his pocket and handed it the policeman.

‘With my compliments, comrade’.

Then he stretched out his arms and slapped Rossel … hard on the back before bursting into booming laughter.

‘Yes, very good. Except for the part about that pompous arse, Shostakovich!’

City of Ghosts, chapter 15

For Russia-in-Fiction, with our penchant for pedantry and detail-spotting, much sport is to be had identifying who is fictional, who a genuine historical figure, and where the two are blurred. Creed name-checks the great Soviet footballer Vsevolod Bobrov and the conductor Karl Eliasberg. The latter famously conducted the Leningrad premiere of Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad Symphony’, during the siege of that city in 1942.

In the post-war years, internal politics blocked Eliasberg’s career; though the brutal interrogation at the hands of the Soviet secret police depicted in City of Ghosts is not attested to in the historical record.

As is to be expected from an author who once lived there, the representation of Leningrad/Saint Petersburg is sure-footed. The down-at-heel reputation of Sennaya Square, established in fiction by Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment, gets its standing confirmed here as the haunt of

blackmailers, spivs, prostitutes and corrupt cops

More uplifting for lovers of St Petersburg is mention of

‘the brightly lit glass globe on top of the House of Books’

Creed even has Revol Rossel pay an investigatory visit to the Pskov-Pechersky Dormition Monastery, with its extensive system of caves. These caves contain coffins with the bodies of monks from centuries past.

According to accounts in the extraordinary, and best-selling, memoirs of Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov), Несвятие святие (Nesvyatie Svyatie, 2012), there are over 14,000 former inhabitants of the monastery laid to rest in these caves.

From the sacred to the profane. The brutality of City of Ghosts is very much of its genre. Brutal deaths, torture, mutilation; all are commonplace in crime fiction, and Russia-in-fiction crime novels are by no means an exception. Take a look at Donald James’s Monstrum or Tom Rob Smith’s bestseller, later turned into a movie, Child 44.

Horrifically, one of the most viciously cruel elements featured in City of Ghosts draws on testimony from the Stalin years and stems from the depraved power of the state as personified in secret police chief Lavrentii Beria. Beria’s rape of girls —sometimes selected from driving around Moscow on the lookout for victims, sometimes family members of people he knew— has been dealt with in sufficient, perhaps more than sufficient, detail by many others.

As a Russia-in-fiction trope, it is not unusual. This blog may even get round to reviewing one book where Beria’s depravity is to the fore; namely, Alan Williams’s The Beria Papers (1973).

City of Ghosts does the business as a work of crime fiction. From the Russia-in-fiction perspective it more than passes muster. The trend for pre-announced trilogies noted in part one of this review has created a trend for pre-ordered sequels here at Russia-in-Fiction Towers.

Part one of this review is here