Part two of this review is here

Future war books are a distinct sub-genre in Russia-in-fiction novels. Over the coming months this blog will review several. Others we will snub.

[Update — review of Red Metal (2019) posted 10 August 2021]

Russia in Fiction approaches such books with a couple of specific prejudices. We are not into military stuff per se; endless eye-glazing pages about high-tech weaponry, artillery placement, and military tactics. Yawn. And we are wary when such books —as sometimes—are more political manifesto than readable fiction.

Red Army side-steps both of these elephant traps with ease. Ralph Peters has written a superbly original account of a war that never was.

Ralph Peters’ Red Army is one of several “let’s imagine superpower conflict” books published in the 1980s.

The forerunner of the genre was General Sir John Hackett’s The Third World War August 1985: A Future History (1978); not a novel at all, it has little in the way of narrative and the whole thing is set up as a history book from the future, including photographs.

Hackett’s The Third World War August 1985 confirms both of this blog’s prejudices against future-war Russia-in-fiction books; replete with military detail and intent on pushing its political line viz-a-viz military expenditure and the Soviet threat. To be fair, Hackett’s later revised version (The Third World War: The Untold Story, published 1982) is a little more of a novel than was its precursor. But only a little.

As we move into the 1980s, Trinity’s Child (1983) by William Prochnau is a US-centric thriller built around the premise of a Soviet nuclear first strike attack on the United States. Tom Clancy’s second novel, after the best-selling The Hunt for Red October (1984), was the 800-page World War III future war book Red Storm Rising (1986), co-written with Larry Bond. And Harold Coyle’s Team Yankee was published in 1987.

And alongside these future war novels, the place of a putative and apocalyptic Third World War in popular culture was bolstered by TV movies such as The Day After (1983) in the US and Threads (1984) in Britain. Both of these graphically depict nuclear missile strikes on major yet somehow standard cities, namely Kansas City and Sheffield.

As a teenager, growing up in Yorkshire and soon to move to Sheffield, I was petrified by Threads.

Within such a literary and cultural setting, Ralph Peters wrote Red Army. Peters blew the conventions of the sub-genre out of the water with this very human account told solely from the perspective of the Soviet soldier going to war.

Red Army sat unread on the shelf at Russia-in-Fiction Towers for several years; partly because it had the look of a novel abounding in military detail. Perhaps this impression was heightened by the fact that Ralph Peters is a retired United States Army Lieutenant Colonel. We expected a US-centric, patriotic tale of narrative jeopardy allayed by military superiority. But once we cracked the spine of our paperback version, such prejudicial assumptions soon disappeared.

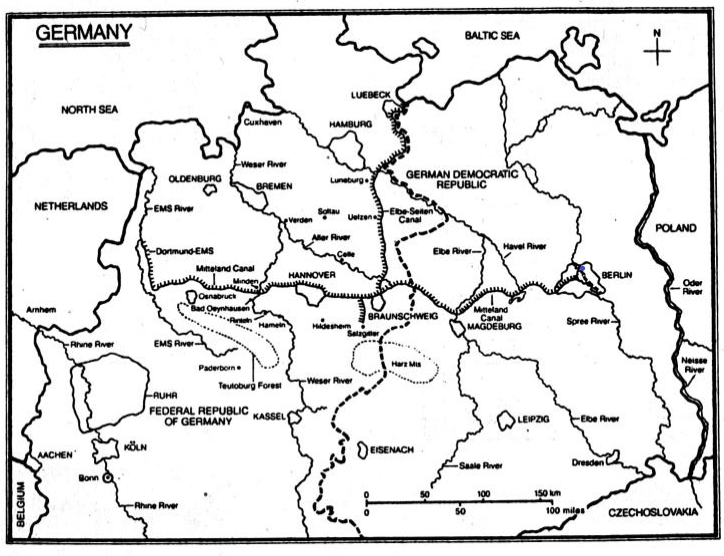

Red Army is a thoughtful and beautifully written book that stands out amongst the other ‘war with the Soviet Union’ novels of the 1980s. Yes, there is a fair amount of military detail about weaponry and tactics; including some tiny and almost illegible black and white maps with arrows sweeping across Germany. But these aspects are not overdone, and nor is Red Army a political thriller of grand strategy and international relations.

The book’s nearly 400 pages are focused entirely on the Soviet army, and specifically on a number of identifiable characters across its ranks and dispositions, when a conventional land and air attack is launched against NATO forces over the frontier between East and West Germany. The reader is at soldier level, on the ground with the troops and their officers as the Soviet forces push towards the Rhine. Realism and human feeling are to the fore; before, during, and after battle, ambush, and skirmish.

Any hints of the overarching geopolitical picture come, as they would for the men at arms, by piecemeal report and rumour. Unlike perhaps all other Russia-in-fiction future war novels, there is little to nothing in Red Army about why the Soviet Union chose to attack NATO when it did. And there is nothing at all from the perspective of the other, the Western, side.

The novel starts in the staging areas of East Germany in the hours before war, and then goes into action with its chosen array of characters.

Without wanting to make too strong a comparison, there are echoes in Red Army of the sort of soldier’s eye view seen in Norman Mailer’s great Second World War novel The Naked and the Dead (1948).

Part two of this review is here