Part one of this review is here

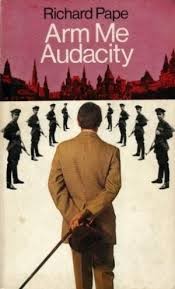

Richard Pape’s reputation as a daredevil and dashing ex-military man turned author, coupled with a handily placed article in a British tabloid, helped to create the impression that Arm Me Audacity was autobiography, fictionalised for reasons of national security. Part one of this review investigates the novel’s background. Part two returns to more familiar Russia-in-fiction reviewing territory. What is the book about? And how does it portray Russia?

In particular, to those familiar with the traits of Cold War espionage thrillers and their representation of the Soviet Union, how present are these in a popular thriller from the 1950s?

Arm Me Audacity was published in 1954 — a particularly pivotal year in the development of the Soviet state. Stalin died in 1953, and Khrushchev had not yet established himself as Soviet leader. There was uncertainty in the West and indeed in Moscow itself as to who was in charge in the USSR. Would it be the new head of the government, Georgii Malenkov, or the new head of the Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev?

The notion of a reformist ‘thaw’ at the highest level of Soviet power was little more than muffled signals and distant hopes.

The attitude of Arm Me Audacity’s hero to the Soviet army at least is made clear early on.

Petheran heard marching feet and immediately on his left was a squad of Soviet soldiers. “My God, what a raw, unholy bunch of bastards,” he muttered. “I’d rather shoot wild boars”

arm me audacity, p. 20

That is what he thinks of the military. His view of Soviet spies is a little more elevated, in terms of acknowledging their abilities and ideological commitment, but scathing in respect of their totalitarian goals.

On the other hand, top-line Soviet espionage men were no fools. They were precisely trained, imaginative, microscopic, specialists in many branches, and incorruptible idealists. But their unshakeable faith in the ultimate liquidation of all opposition systems, their profound belief in the eventual creation of a monolithic communist universe, was staggering. They believed, quite genuinely, that the formula of the Politbureau was all-wise, all-good, all-perfect, that everything and everybody outside of Russia was rotten, warped, conspiring and evil.

arm me audacity, p. 41

The standard tropes of Soviet behaviour in spy fiction are present. Soviet agents are themselves under constant surveillance by one another, and fear execution for the slightest mistakes. (See the review of Red Sparrow for discussion of how difficult to shift such an idea has become in the genre).

And talking of Red Sparrow, the notion of sexpionage is likewise present back in the 1950s. Arm Me Audacity‘s hero, Anthony Petheran, posing as a defector, comes under understandable suspicion, and so Nina, a female Soviet agent, is provided for his sexual pleasure, with the intention of drawing out Petheran’s inner thoughts.

What about how the Soviet Union was understood, in these nascent Cold War days? Richard Pape gives one of his senior Soviet intelligence characters a speech, accompanied by vodka of course, in which he extols the virtues of both Russia and of Communism. Such a merging of Russian nationalism with the internationalist dream of the Communist state is a notable feature of the book’s portrayal of the USSR. It is not with rhetoric about equality and the emancipation of the workers that Soviet intelligence seeks to impress Petheran, even though he is posing as a committed Communist. Instead, a picture of Russian imperial grandeur is presented.

‘Nina will meet you in Moscow and show you the sights. You will walk along the banks of our holy river Moskva. Do you know, Comrade Antonni, our capital was once called Holy Moscow?

‘… Nina will show you the tower of Ivan Veliky. You will go to Kremlin Hill, and our great and glorious Kremlin itself will stagger your eyes. It is the heart-beat of the Russian Empire. One day it will be the heart-beat of the Russian world empire, when your country, Comrade Antonni, will be a British-Soviet Republic.

‘… Yes, yes,’ he exclaimed, absorbed in his oratory, ‘you will see the nineteen Kremlin towers, the Bolshoi Kremlevski Dvoretz

‘… And the Britishers talk about their wonderful box of tricks, Buckingham Palace – bah!

‘ … Wait till you see the Red Square, Soborny Square, Mokhovaya Square and the Granovitaya Palace – and the cathedrals! The Uspensky Cathedral, the Blagovyeshenski Cathedral, the Arkhangelski Cathedral

‘… Let the British shriek about their monstrosity, Westminster Abbey. I give you my word, Comrade Antonni, Moscow will stir your soul

‘… Moscow is a great and historic capital, but its past history will be as nothing compared to the greatness of its future as the centre of Communist world power.’

arm me audacity, pp. 83-84

A central plot feature of Arm Me Audacity relates to documents which would prove Soviet culpability for the infamous Katyn massacre, when thousands of Polish officers were killed in 1940. For decades the Soviet regime blamed this atrocity on the Nazis. It was only at the end of the Soviet Union that an official enquiry, set up under Gorbachev and completed under Yeltsin, acknowledged Soviet responsibility. Clearly the truth was already out and available in paperback thrillers in the UK in 1954.

Arm Me Audacity is a fascinating book for those interested in the portrayal of Russia in fiction. Such books from the 1950s do not regularly turn up on the shelves of second-hand bookshops, nor in that format that has proved such a boon to 21st century genre connoisseurs, the re-issued ebook.

In fact, forget for a second the portrayal of Russia; just to be taken back to some of the general period detail from 70 years ago fascinates. For example, I had to remind myself that ensuite rooms were scarcely a thing in many European hotels in the 1950s. This becomes a minor plot point, as Arm Me Audacity’s hero uses a visit to the bathroom, situated along the corridor from his hotel room, in order to evade surveillance by Soviet agents.

Arm Me Audacity is an enjoyable read as a thriller. The plot is not obvious and the action swings along entertainingly. From the Russia-in-fiction perspective, it intrigues.