The Betrayal is not the first book reviewed on the Russia in Fiction blog that is set in Leningrad in the opening years of the 1950s. That honour goes to City of Ghosts, which is set in 1951. Helen Dunmore’s novel takes place a year later, in 1952.

In both cases, the key fact in relation to setting is that Stalin was still alive.

Before Stalin’s death in 1953, the feeling that the demise of his repressive dictatorship was long overdue was particularly keenly felt in Leningrad, a ‘hero city’ that suffered more than most during the Second World War.

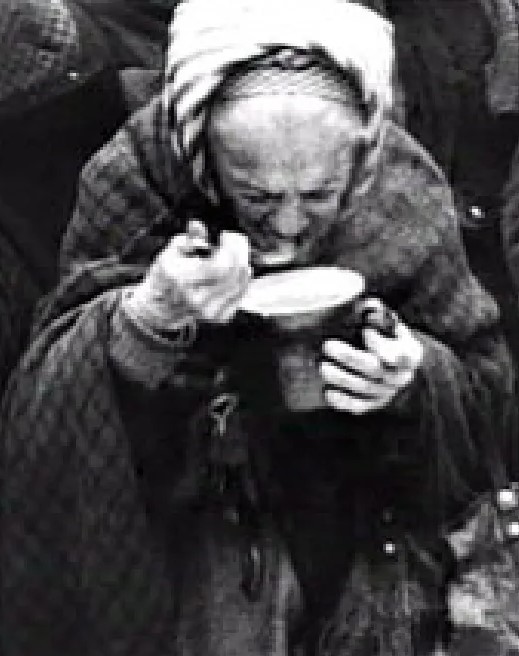

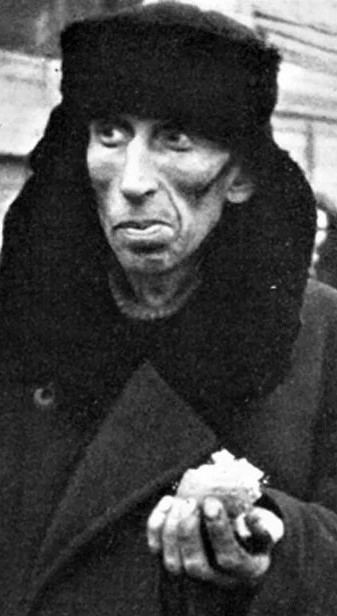

The idea that —after the hardships and terrors of the 1930s and 1940s— the Soviet people should at last begin to feel the oft-proclaimed benefits of Communism seems to have been widespread. Later interviews with those who had survived through the siege of Leningrad not only confirm such a sentiment, but register too the deep and frustrating disillusionment felt when Stalinist repression returned with avengeance.

Russia in Fiction recalls one such interviewee reminiscing almost fondly about the war years themselves, as a time when Leningraders, cut off from the rest of the Soviet Union by Nazi encirclement, felt themselves freer than they had been for years in relation to oppressive oversight from the Kremlin.

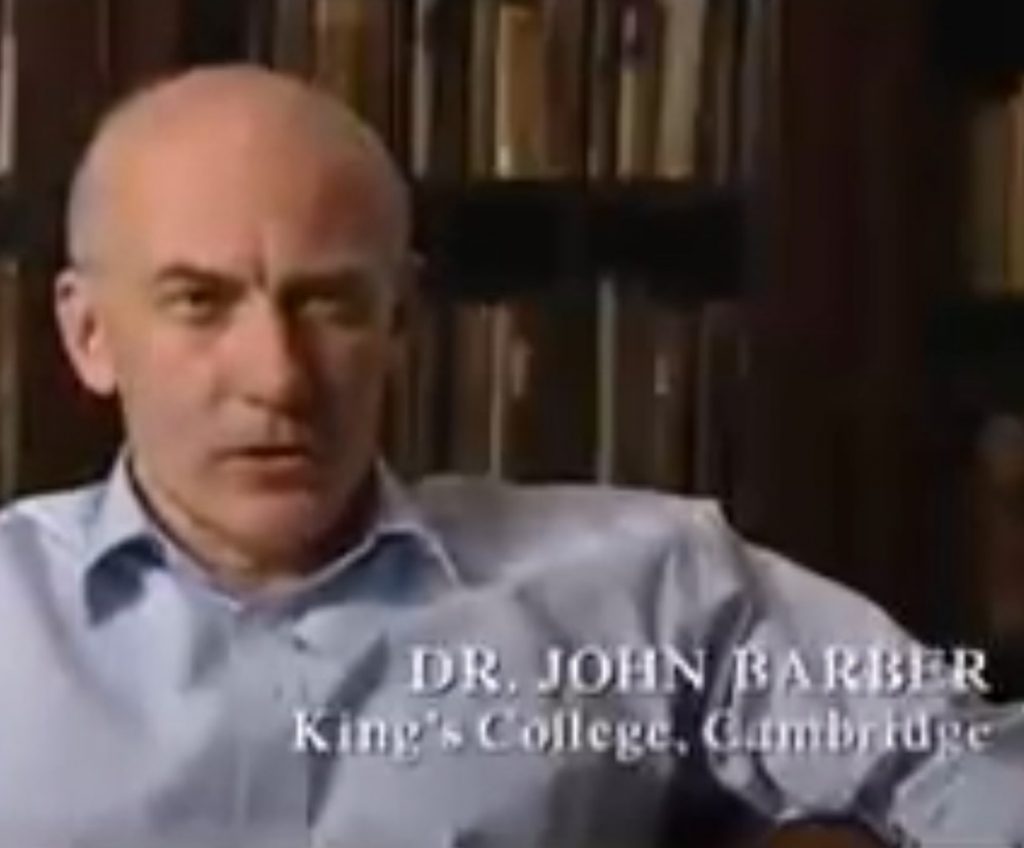

(That interview is from the BBC Timewatch documentary Stalin and the Betrayal of Leningrad, details of which can be found here, in a short piece written by the late John Barber of the University of Cambridge.)

John Barber was an excellent and erudite scholar, who sadly passed away in July 2021.

The Betrayal is about the persistence of repression under the brutal dictatorship of Josef Stalin into the second half of the twentieth century. The novel’s central characters —husband and wife Andrei and Anna— discuss such matters only secretly together.

‘But maybe some time, in the not too distant future, things would start to get easier. ‘No one can live for ever,’ they whispered to each other. Even now, when they’re alone, they go no further than that. He is an old man, even though his polished-up photographs make him look young as he presides over the great parades. Over seventy now.’

‘Georgians live for a long time’, said Andrei once.

‘Only if they stay in Georgia,’ Anna replied.

The Betrayal, p. 27

In The Betrayal, Helen Dunmore (1952-2017) has crafted a story marked from the first chapter with foreboding.

Andrei is a relatively young doctor in Leningrad’s main hospital. As the novel opens, one of Andrei’s colleagues, Dr Russov, asks him —with uncharacteristic unctuousness— for a favour. Ostensibly that favour is to offer a second opinion on the case of a ten-year old boy. Andrei is puzzled as to why this normally abrupt colleague, who looks out for himself at least as much as he looks after his patients, is seeking his involvement.

‘I’m not sure I understand you. What are your initial findings?’

Russov gives a sudden harsh bark of laughter which transforms his face completely. He looks almost savage. His short hair seems to bristle.

‘My “initial findings” are that this patient is the son of — of an extremely influential person … He’s Volkov’s son,’ says Russov abruptly.

‘Volkov’s?’ My God. It’s one of those names you only have to say once, like Yezhov or Beria. Andrei’s heart thuds, and he has to clear his throat before speaking. ‘The Volkov, you mean?’

The Betrayal, p.3

Volkov is a senior MVD (KGB) official, and Russov is trying to distance himself as soon and as far as possible from any contact with the Security Services. Andrei’s friends, and his wife Anna, advise him to do the same.

This is a world where to be noticed by the authorities is to court peril. The notorious knock on the door in the middle of the night is still feared. If the boy can be cured, then all is well. But if —as it turns out— his sickness follows an ever more harrowing path, then a man like Volkov is not going to accept that his power is futile in the face of disease. Someone must be at fault, treachery must be present, wreckers must be at work.

The power of The Betrayal builds as the reader gets to know the life and loves and dreams of Andrei and Anna. Both survivors of the unimaginable horrors of the siege of Leningrad, only a decade earlier, they live with Anna’s younger brother, Kolya, a teenager whom they have brought up as if they were his parents.

The Betrayal serves as a sequel to Dunmore’s 2001 novel, The Siege, which tells the story of Andrei, Anna, and Kolya when Leningrad is encircled by the invading Nazi forces in 1941-43. Characters aside, however, each novel is a free-standing story that does not depend on the other.

That said, the narrative power of The Betrayal is enhanced by knowledge of its central characters’ past, and Dunmore provides this through Anna’s reminisces as she sorts through diaries and drawings from those brutal days.

Anna reaches for the top sketchbook, and opens it.

There is a drawing of a tram, stuck in a snowdrift. Its windows would be full of frost, except that a shell blast has shattered them. Through the gaps you can see a woman sitting, muffled in coat, hat, scarf. Her head has fallen to her chest. She is dead.

On the next page there is a snowdrift. A hand sticks out of it, but people walk by, not even noticing, intent on their next step. The drawings are made in strong, thick lines, like cartoons.

… Marina had said, ‘You must draw everything, Anna. One day people will want to know what happened.’

But Marina was mistaken. People have to bury their stories. What’s wanted is an acceptable version, not the truth. Certainly not Leningrad’s truth. Anna drew the Sennaya market, with its terrifying vendors of meat whose origin mustn’t be questioned too closely. She drew the face of the man who stole her sledge with the sack of wood she’d scavenged, and the face of Zina when she came to their apartment door with her dead baby in her arms. At the bottom of the secret compartment there are her larger drawings …

Here’s Marina, alive again, carefully peeling off the top, painted layer of papier mâché from Kolya’s toy fort. There is nourishment in the paste that held the layers of newspaper together. They will cook and eat the papier mâché.

The Betrayal, pp. 78-79

Anna is right; people do have to bury their stories. And as the prognosis for the Volkov boy worsens, this is literally what Anna does, taking precious family papers out into the countryside, digging a hole and carefully placing them in it so that nothing even slightly incriminating can be found should their apartment be searched.

Russia in Fiction is not that bothered about the notion of spoilers. It seems clear from the opening chapters that engagement with the Volkov case brings an ever darkening cloud over the otherwise bright future that Andrei and Anna see before them.

Nonetheless, we will restrain from going into too much detail about precisely how events unfold. The beauty and power of The Betrayal lie in its characters and detail. Those other doctors who have been involved with Volkov’s son suddenly apply for posts far away from Leningrad; better to uproot their lives than to lose them. For Andrei and Anna somehow this does not seem a realistic option, and they continue on living as the rumblings of approaching terror grow steadily more insistent.

Fatalistically, they begin to make plans. Andrei seeks to persuade Anna to move out of the city. He reminds her of the tactics adopted by acquaintances during the Great Terror of the late 1930s.

‘You know Lena?’

‘Of course I do,’ she says with a touch of asperity.

‘Her father was arrested in ’37. She said her parents had an agreement that if one of them was arrested, the other would denounce them so there’d be someone left for the children.’

‘Hmm. That didn’t work for most people.’

‘It did for them.’ …

‘But if they arrest you too, Anna – ’

‘Don’t talk like that! No one’s been arrested. You’ve done nothing.’ But suddenly, hearing herself, she’s shaken by a desire to laugh. You’ve done nothing! Whoever heard of anything more childish and unrealistic? It wasn’t me! It’s not fair!

‘Anna, please don’t! Don’t cry.’

The Betrayal, pp. 168-169

The Betrayal ends, predictably enough for a novel set in the Soviet Union that begins in 1952, with the announcement in March 1953 that Stalin has finally died. Though for Andrei and Anna, and for others caught up in the Volkov case, and for all the wider circle of victims of what became known as the Doctors’ plot —hinted at in Dunmore’s novel— the dictator’s death comes too late.

A one page final chapter serves as The Betrayal’s afterword, consisting of a few paragraphs of historical fact setting out the immediate easing of repression after Stalin’s passing, the exoneration of those caught up in the Doctors’ plot, and the arrest and execution of the MGB officers responsible for their persecution. All of this is a little separate from the fictional story of Andrei and Anna. Except for the final sentence of the novel, which takes four words to bring their story to a conclusion.