Part one of this review is here

The central character of The Moscow Club —’the first great post-Cold War thriller’— comes straight out of the standard thriller stable. There is not a great deal of room for doubting that he is on the side of the angels and will triumph.

The reader knows, from the moment we encounter him rock-climbing, on vacation from his role as genius Soviet analyst with a secret CIA off-shoot agency, that Charles Stone is always going to win through.

That is not a plot-spoiler. It is just obvious. Stone’s work with an off-the-books CIA branch (slightly reminiscent of the off-the-books British agency for which Petra Reuter works in Mark Burnell’s superb novels) plunges him into the hunt for plotters in the KGB and the CIA alike. It then gets personal when his godfather (Winthrop Lehman) and his father (an academic, expert on Russia, broken by spying allegations and prison during the McCarthy witch-hunts of the early 1950s) turn out to be involved in some way.

Oh, and Stone’s estranged wife also comes into the picture. Handily, from many perspectives, she’s a beautiful, blonde, Moscow-based, TV reporter.

From the ‘how well does he know Russia’ perspective, The Moscow Club gets off to a terrific start, with a dead-drop in Moscow public toilet. At the risk of sounding a bit strange, here at Russia in Fiction we count this as one of the most memorable opening scenes we know. And that is purely because, if you ever visited a public toilet in the Soviet Union, you will recognise the accuracy of Joseph Finder’s description

… down a flight of concrete steps. The acrid smell of urine got stronger and more overpowering as he descended. The granite and concrete facility was lit by a bare bulb on the ceiling, which cast a yellowish glare over the fetid interior, its urinals and broken porcelain sinks and splintered wooden toilet stalls … the smell here was oppressive. [He] gagged.

The Moscow Club, p. 5

Reading that is to be taken back to late Soviet Russia. It brings back memories of particular public toilets just like that but without the luxury of the single bare bulb, gingerly stepping through Lord-knows-what, guided only by the flickering half-flame from a lighter, having just lit up a cigarette in an attempt to somehow repel the stench.

Let’s elevate things a little.

Finder’s knowledge of late —very late— Soviet-era politics feeds into the complexity of The Moscow Club‘s plot fairly accurately. Writing before the August coup of 1991, he points out that Soviet coups become more likely when the General Secretary is on holiday

Khrushchev had been overthrown when he chose a bad time to take a vacation on the Black Sea. Gorbachev had almost been ousted in 1987 while on holiday. If you happen to have the misfortune to be one of the Kremlin’s rulers and you want to hold on to your power, the rule of thumb is: Don’t take vacations. And don’t get sick.

The Moscow Club, p. 47

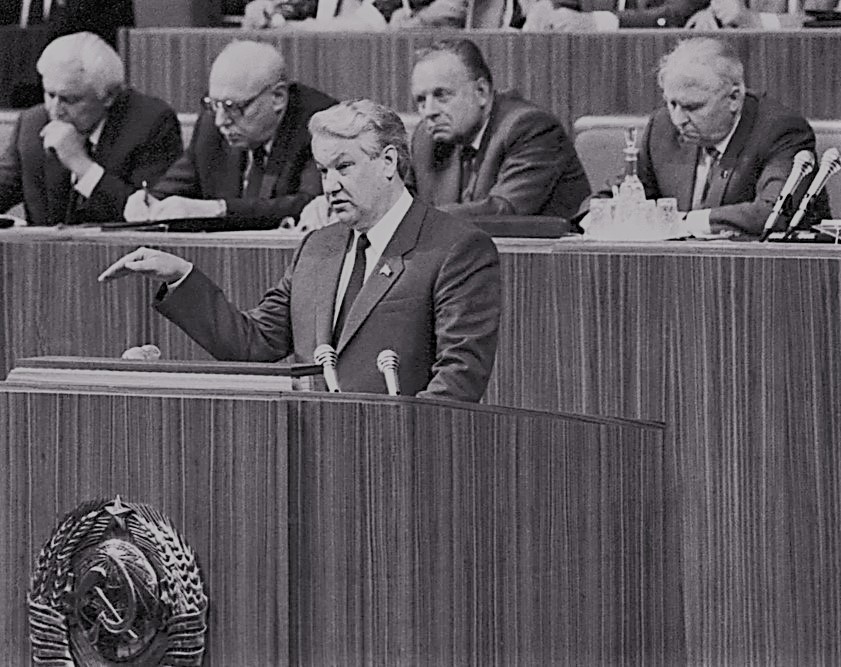

The reference to 1987 is presumably to the clash between Boris Yeltsin, pushing for faster reform, and Yegor Ligachev, taking a more cautious approach. This began to boil over when Ligachev chaired a Politburo meeting in September 1987, whilst Gorbachev was on vacation. It culminated in a rare semi-public and angry voicing of differences during speeches at a Central Committee plenum in October. Yeltsin strongly criticised Ligachev, who responded in kind, with Gorbachev as arbiter trying —as ever— to balance support for democratisation with the preservation of Party power. Such outspoken criticism was not the done thing in the Soviet Communist Party; at least not in 1987.

Yegor Ligachev died only a few weeks ago, in May 2021.

Finder is also astute enough to note that the KGB as a whole was not, at least at first, against Gorbachev’s reforms.

But the people at the KGB, infinitely more cosmopolitan than their military comrades, saw the sense in Gorbachev’s plan for reform, saw that he wasn’t weakening Russia but (in the long run, anyway) strengthening it, and so they stood behind him throughout the turmoil.

The Moscow Club, p. 94

Russia in Fiction enjoyed too — as often, as much for personal reasons as anything else— a vignette towards the end of The Moscow Club, when the American president is visiting Gorbachev in Moscow. A mother points out to her child …

… whispering excitedly ‘Can you see Gorbachev? That’s Gorbachev! And there’s the president of the United States!’

The Moscow Club, p. 527

This —along with the pin-badge we picked up at the time—reminds Russia in Fiction very much of the reaction of Soviet citizens, observed when President Reagan visited Russia in 1988, along the lines of “how could this thing be?!”.

The complexity of The Moscow Club‘s plot means that this is one of those thrillers that might leave the reader wanting to go back and check a few things. When Russia in Fiction did that, we spotted what seems to be a plot gaffe. Stone is early on lauded for skilfully and Kremlinologically finding out which member of the Politburo is secretly ill, only for, about 500 pages later, Stone and his wife to endanger a Kremlin doctor’s life by getting him to find out the very thing that Stone had already discovered.

Joseph Finder has gone on to a fairly stellar career as a thriller writer, moving away from Russia in fiction to the world of business for his themes.

Although Finder’s second novel, Extraordinary Powers (1993), was also Russia-related, dealing with psychological experiments as well as a theme that remains to the fore amongst observers of Russia today, ‘a multi-billion dollar fortune … spirited out of Russia in the last days of the Soviet Union’.

Part one of this review is here