(Part two of this review is here)

A quick review of what was for Russia in Fiction a quick summer read. If you fancy a spy/political thriller for the beach or the pool, this will do the trick.

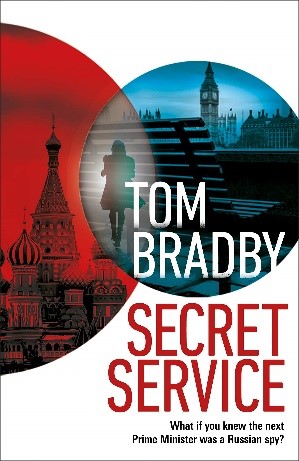

Secret Service is the first in a trilogy written by Tom Bradby, a nationally known journalist and newscaster in the UK.

Bradby had been on the periphery of our Russia-in-fiction radar for a while, because he penned a novel called White Russian a few years back (2004), setting it in St Petersburg in 1917. (We’ve read White Russian since writing this review, but have not yet got round to posting about it on this Russia in Fiction book blog).

Then, browsing in Stamford’s independent bookshop, Walkers Books, during a few days summer break, we came across Bradby’s Double Agent (2020) in hardback.

Then, browsing in Stamford’s independent bookshop, Walkers Books, during a few days summer break, we came across Bradby’s Double Agent (2020) in hardback.

A swift online search revealed that Double Agent is the second in a trilogy, and helpful reviews noted that it was very much a sequel to the unresolved plot elements in the first book of the trilogy, Secret Service. So we bought Secret Service and read it in a matter of hours.

A trilogy about a Russian mole high in the UK establishment? Even those with a casual awareness of espionage fiction will know that the idea is scarcely original. Bradby is no Le Carré, but very few are, and ditto, Secret Service is no Tinker Tailer Soldier Spy.

For that matter, its lead MI6 character, Kate Henderson, is no George Smiley. Writing almost half a century on from the first in Le Carré’s Karla trilogy, Bradby’s cast is far more contemporary.

Henderson is a senior MI6 officer but also a working mum struggling to balance saving the country with bringing up two typically teenage children and coping with a senile mother in a nursing home. Henderson’s assistant is a gay Asian man by the name of Rav. Her husband is a senior civil servant, and the two of them are very much in the Westminster/ Whitehall/metropolitan world.

So far, so up-to-date. But there is still much that would be recognisable from decades ago.

There is a foreign secretary and a head of MI6 who went to public school together, big bad Russia is the unreconstructed enemy, and the plot revolves around two of the staples of the espionage thriller genre — a mole hunt with multiple suspects leading to a big reveal in the final chapter, and the Manchurian candidate idea of a Russian agent in place being supported to the top job by Moscow. (See, for example, Martin Gross’s Red President or Alan Gold’s The Jericho Files, to name but two other examples of the latter plot device).

The online reviews of Secret Service are multiple and, taken as a whole, pretty accurate. Bradby has written an enjoyable thriller. (It kept me up into the small hours reading it, but there again, I was on holiday). It is not the sort of book to analyse too much; best to enter in and enjoy.

What about the Russia-in-fiction element?

As for the Russia-in-fiction elements, Bradby goes for a straight down the line buy-in to the standard thriller-writer depiction of Putin-era villains, such as the mega-rich oligarch who is indistinguishable from the Russian state and hand-in-glove with the Russian secret services. Henderson tracks him and his English public school educated son as they dot around the Mediterranean on a super-yacht plotting the downfall of the West. Daniel Silva, for one, did this stuff a decade or more ago, in two of his best books —Moscow Rules (2008) and The Defector (2009).

Whilst there are any number of Russia-related thrillers over the past decade or so that reference the Litvinenko murder, or more recently, the attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, Bradby is original —so far as Russia in Fiction knows— in alluding to the tragic and awful-to-contemplate death of Gareth Williams.

Williams’ body was found inside a bag in his bath, zipped up. The Wikipedia page Death of Gareth Williams gives the complex and gruesome story in more detail than we are going to do here, but in short it notes that Williams worked for GCHQ, had been seconded to MI6, and that there were some reports that he was working on money-laundering that might have involved the Russian mafia. Information about his work would of course not be public knowledge, but it is known that the coroner at the inquest delivered a narrative verdict and the lack of certainty around the case has led to much speculation.

In Secret Service, Bradby has the British secret service staff discussing a case where someone is found dead at the hands of his fictional Russian operative, hanged naked with an orange in his mouth:

‘The inquest will say he accidentally hanged himself while taking part in a sex game. The Russians very carefully and deliberately made it look like Gareth Williams.’

‘The guy they found zipped up in a bag?’

‘Yes, sorry, before your time. He was a really bright guy working on how the Russian Mafia and oligarch class were laundering their money. We should have learnt our lesson.’

As a side note, there is also at least one Russian-language thriller that draws on the murder of Alexander Litvinenko, and does so in more than a passing reference.

As a side note, there is also at least one Russian-language thriller that draws on the murder of Alexander Litvinenko, and does so in more than a passing reference.

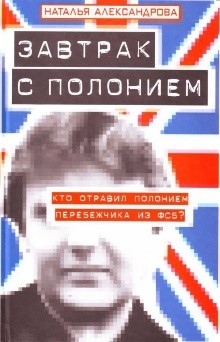

Best-selling Russian author Natalya Aleksandrova published a thriller in 2007 with the none too subtle title Завтрак с полонием – which translates as Polonium for Breakfast and has a picture of Litvinenko on the cover.

Russia in Fiction’s ‘not really a review’ of Завтрак с полонием is here.

(Part two of this review is here)