Way before the death of Stalin became the title of a graphic novel which then in 2017 became a comic movie, banned in Russia, the actual passing of the Communist dictator in March 1953 provided the plot for several thrillers written by British writers.

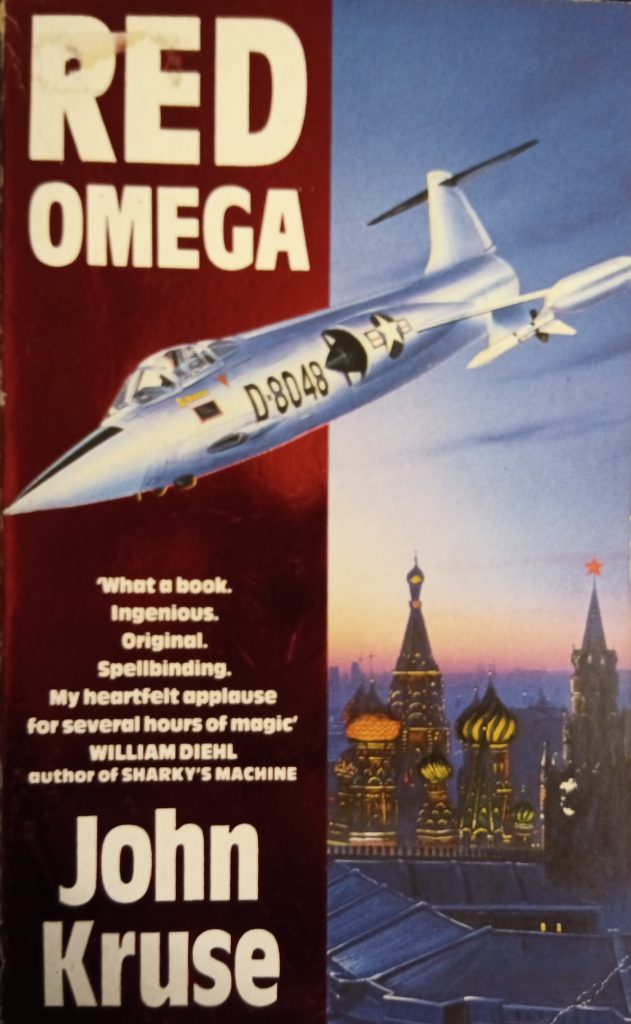

The novel reviewed before this one —Robert Harris’s Archangel (1998)— begins on the day of Stalin’s death. John Kruse’s Red Omega (1981) develops the fictional notion that Stalin was assassinated. Barnaby Williams’s Revolution (1994) has Stalin suffocated by his Politburo subordinates.

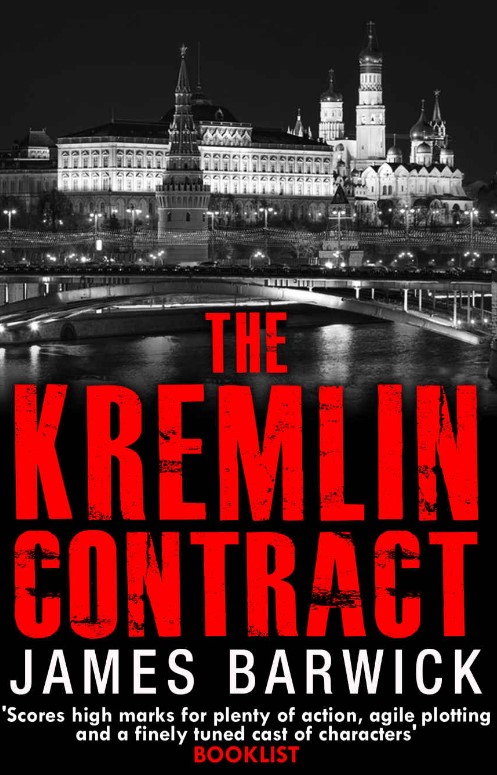

The Kremlin Contract similarly has the theme of Stalin being assassinated. And almost all of its characters, on both sides of the Cold War divide, want him dead.

In The Kremlin Contract, dying Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin, orders his armed forces to ready themselves for the invasion of Western Europe. The rest of the Politburo, along with much of the leadership of the Soviet Army, believe this to be madness on an apocalyptic scale. Sure, plans for a rapid advance to the Atlantic might be plausible, but the risk of NATO staging a nuclear response is high and threatens millions of lives and the very existence of the Soviet Union.

The difficulty is that no one is in a position to countermand Stalin. And so a plot is hatched, with eventual American support, for the assassination of Stalin.

The man chosen for the job is a Soviet MGB (KGB) officer of American parentage, Alexander Trenton. Barwick sets up Trenton’s background in the opening pages of The Kremlin Contract, a prologue set in Georgia in 1920. As the Red Army advances on the port of Batumi, the US Consul there —Charles Trenton— flees aboard a US navy ship sent to the rescue. His wife, a woman with Communist sympathies, deliberately stays behind with their young son, Alexander, to welcome the Reds; whose commander was a certain Joseph Stalin.

Somewhere a band started to play. An atmosphere of expectancy began to build. The crowd of villagers began to thicken.… Someone started a chant. Quickly taken up, it swept through the throng and was driven on by the stamping of feet. “Sta… lin, Sta… lin, Sta… lin.”

The young American woman clutched the boy and yelled the name with a passion that seemed to vibrate through her whole body. “Sta… lin, Sta… lin, Sta… lin.”

THe Kremlin Contract, p. 17

Wind forward 33 years and Alexander Trenton is an increasingly disillusioned officer in Stalin’s secret police. His overbearing mother lives in some style in Moscow with Alexander’s superior officer. His father is a leading academic expert on the Soviet Union back in the United States.

The Kremlin Contract is a serviceable enough thriller. As in Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal (1971), the assassin and his target are identified early on, and any tension comes from method, setbacks, and outcome. The Russia-in-fiction thriller staples of sex, a bit of brutality in the cellars of the Lubyanka, and the unveiling of a mole in the US establishment are all efficiently dispensed.

Barwick even delivers a version of the ‘cremated alive’ story that makes regular appearances in Cold War thrillers designed to emphasise KGB brutality.

This macabre motif is sourced from an alleged actual case. In the post-Soviet era, the story has become connected to the execution of Oleg Pen’kovsky, a Soviet military intelligence (GRU) officer who spied for the US and the UK in the Khrushchev years and was caught and executed in Moscow. According to later circulated rumours that have achieved the status of received wisdom amongst espionage afficionados in both Russia and the West, Pen’kovsky was killed by being strapped to a stretcher and wheeled alive into a crematorium furnace – with the process being filmed and shown during Soviet intelligence training as a warning to other potential traitors.

The Pen’kovsky story is disputed on several levels. Was it Pen’kovsky on the stretcher? Was indeed anyone executed in this manner? Was Pen’kovsky himself a dangle spreading disinformation on behalf of the Soviet Union? Such doubts have not stopped the motif from regularly appearing in western spy fiction —sometimes mentioning Pen’kovsky, sometimes not. Examples include the work of Tom Clancy (Red Rabbit), Nelson DeMille (The Charm School) and Charles McCarry (Old Boys).

In The Kremlin Contract, a Soviet traitor is thrown into a furnace, sans stretcher, and there is no reference to Pen’kovsky. All of which might itself shed some light on the possible urban myth status of the Pen’kovsky story.

The origin of the idea that a Soviet traitor was burned alive pour encourager les autres is Viktor Suvorov’s loosely autobiographical book Inside the Aquarium: the making of a top Soviet spy (1985); later known simply as Aquarium. Its dramatic and graphic prologue describes in vivid detail (here, if you can cope), an old black and white video played to new members of the Soviet military intelligence, the GRU, in which a traitor is executed by being slowly fed into the flames. Reading around Russian and English sources regarding the veracity or not of this story, Russia in Fiction can conclude little more than case not proven.

In Aquarium, Suvorov explicitly does not know the name of the alleged victim, who is described simply as a Colonel. An article by Russian-American Nobel Prize winning poet, Joseph Brodsky, in 1992, named the Colonel as Oleg Pen’kovsky, albeit with the caveat ‘or so I was told’.

It is no surprise that The Kremlin Contract, published in 1987, should deploy the ‘cremated alive’ motif, just a couple of years after it caused a sensation when Aquarium was published.

******

From the Russia-in-fiction perspective, the recurrent use of Stalin’s death as a plot device fascinates. Of course The Death of Stalin is now well known through the star-bespattered 2017 film directed by Armando Iannucci, which was based on the French graphic novel La Mort de Staline by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin.

(Russia in Fiction does books, not films. But we have just discovered the movie review podcast series Russophiles Unite! that reviews Russian and Russia-themed films, including The Death of Stalin).

A quarter of a century or more before La Mort de Staline, Stalin’s death became a favoured plot device for British authors of strikingly similar backgrounds.

The ‘James Barwick’ who authored The Kremlin Contract was in fact two people, the writing duo of Donald James and Tony Barwick. The former is a doyen of the Russia-in-fiction genre. We have reviewed one of his Inspector Vadim novels (Monstrum) and are saving his best work (The Fall of the Russian Empire) for a special occasion on our march to a hundred reviews. [Update, we finally published this review on 9 September 2021]

His occasional co-writer, Tony Barwick, was, like Donald James, a regular television scriptwriter on action programmes of the 1960s and 1970s.

As indeed was John Kruse, whose excellent debut novel Red Omega (1981) revolved around an attempt to assassinate Stalin.

(Russia in Fiction has reviewed Kruse’s second novel The Hour of the Lily, 1987).

Their TV writing credits, as their age and background, have sufficient similarities to imagine that James and Barwick must surely have been acquainted with Kruse. Or at least with each other’s work. After all, they all wrote episodes of The Persuaders! starring Roger Moore, and Kruse and James wrote for another Moore vehicle, The Saint.

The Kremlin Contract was re-issued as an e-book in 2015, with a fine black and white picture of the Kremlin at night on the cover. It is worth a read for lovers of Cold War thrillers.

Leafing through Russia in Fiction’s tatty paperback edition, it is striking how such a seemingly slim and light-weight book packs so much in. In the physical sense, were it published today the font would be larger, the spacing wider, and the page count far more than the 250 in our version.

In the content-sense, The Kremlin Contract ticks off regular elements of the genre with ease — the dictator who has gone so far that his own side work with ‘the main enemy’, the United States, to stop him; the gradual dawning on a privileged Soviet official that most of his compatriots do not live as he does; the final chapters where our heroes attempt a border crossing. All these and more can be found in The Kremlin Contract.