Before our next review goes somewhere slightly different (the town of Azov, to be precise), Russia in Fiction fancies bringing together a few themes from our first year of blogging. Charles McCarry’s Old Boys is a fine book for doing that.

As its name denotes, in its reviews the Russia in Fiction blog probes the fiction written and the Russia portrayed. Old Boys came from the pen of one the classiest of literary espionage writers of the Cold War years, Charles McCarry (1930-2019). And its decades-spanning take on Russia serves as a summation of Russo-specific themes often to the fore in fictional renderings.

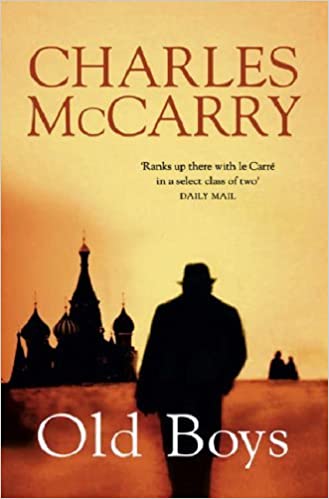

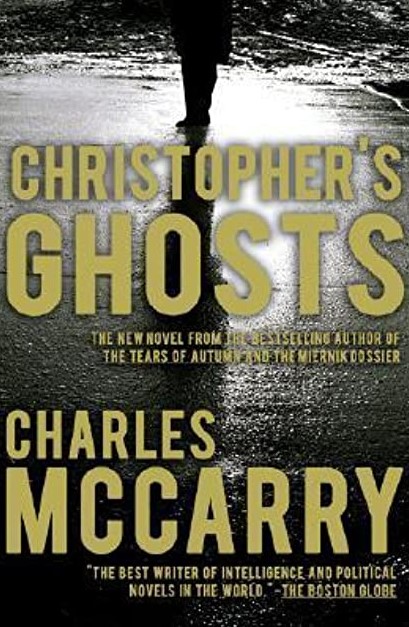

What is more, the edition of Old Boys that Russia in Fiction read has enough on its cover to keep us going for a paragraph or two before we even get to the novel itself. Specifically, Silhouette, Red Square; and a degree of pre-approval —from almost two decades before we devised it— of our ranking of great Cold War spy novelists.

We have often bemoaned the lack of originality in Russia-in-fiction book covers over the past nearly three decades. The Silhouette, Red Square post illustrates, with the help of a far from comprehensive set of 18 examples, which does not include the Old Boys cover at the top of this review. Of its type, this particular cover is a pretty good one.

The silhouetted figure’s hat and coat bring to mind George Smiley, as portrayed by Alec Guinness, in the BBC’s 1979 and 1982 dramatisations of John Le Carre’s novels Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974) and Smiley’s People (1979).

Ranks up there with le Carré in a select class of two

DAIly mail, 2004

The quote on the cover could be taken as yet another example of the tendency for publishers and lazy reviewers to compare any novel about spying and Russia, whatever its quality or approach, to the work of John le Carré. There are dozens, may be even hundreds, of examples of this phenomenon. If we had a rouble for every time we had read the phrase ‘the new le Carré’ …

But in this case, the reviewer is not wrong. To repeat Russia in Fiction’s overview of great Cold War spy novelists (as set out in our review of Paul Vidich’s The Mercenary), it goes something like John le Carré, rhymes with Charles McCarry, and add a couple of Bobs (Robert Littell and Robert Moss).

When Old Boys was published in 2004, Mark Lawson’s review noted of Charles McCarry’s work that

despite regularly ecstatic reviews which properly acknowledge him as a match for his best-selling English equivalent John le Carré … the novels have never been consistently in print and have an almost samizdat existence

Mark Lawson, the Guardian, 18 September 2004

Happily, the availability of books by Charles McCarry has improved in recent years, as both paperbacks and e-books

McCarry’s George Smiley is Paul Christopher, and Old Boys was something of a come-back novel in the Paul Christopher series —though it is more about Christopher’s cousin Horace than about Christopher himself. It was published over a decade since Second Sight, the previous novel built around the character of Paul Christopher.

Old Boys is not a novel about Russia as such, but there is a strong Russia-related element within it. Specifically, the plot theme of relevance is one that is familiar in post-Soviet thrillers, and not unknown in those of the Cold War era, namely, missing nuclear weapons. In this case

at least twelve compact nuclear warheads of the type designed by the Soviets to be backpacked into combat by their special forces.

Old Boys, p. 31

These nuclear weapons are thought to be in the possession of a Palestinian terrorist whose assassination Horace is supposed to have organised —apparently unsuccessfully— many years earlier. Talking of apparent deaths, the novel’s launch point is the disappearance and presumed death of Paul Christopher himself, which leads to Horace gathering together a group of ageing and rather sickly intelligence veterans —the eponymous ‘Old Boys’— to go in search of him.

Plot features unrelated to Russia include the search for Christopher’s mother as well as for Paul Christopher himself, and diversions into biblical history, as she is said to be in possession of a scroll written in the first century as a report by a Roman secret service officer who had inserted an agent into the entourage around Jesus Christ. Locations are similarly prodigious —with our own favourites being, as ever, the places we know, such as the Campo dei Fiori in Rome and the Ponte Vecchio in Florence. Old Boys is ambitious and its development and denouement get ever more so.

As part of this globe- and century-hopping yarn, there is a middle section (Part Three) involving a visit to Moscow. The set-up is that Horace and his companion are returning to Moscow for the first time in 20 years; in other words since the immediate post-Brezhnev interregnum of Andropov and Chernenko. As if in reference to these two decrepit Soviet leaders, Part Three begins:

The last time I saw Moscow, twenty years before, her heart was barely beating. Now it seemed to be fibrillating. We were confronted everywhere by wonders. Restaurant food was edible, waiters smiled for tips. Bare skin and German cars were much in evidence, money was a more popular topic of conversation than the weather, the jokes were about sex instead of the Politburo.

Old Boys, p. 119

From an intelligence security perspective, McCarry’s take on early 21st century Moscow riffs on the now familiar thriller theme of the security services and the mafia being closely intertwined.

For those whose interests are not just in Russia in fiction, but also in espionage in fiction, as ever with ex-CIA officer McCarry, there are some interesting bits of tradecraft. Knowing that the author is a former US intelligence officer, what do we make of the assertion that ‘desirable tables in fashionable restaurants are routinely bugged by counterespionage people in every country in the world’ (p. 39)?

Tradecraft terms are thrown in; for example, ‘waterfall surveillance’

involves walking right at the target face to face and making eye contact instead of sneaking along behind in the usual way. It requires a small army of agents, all targeted on a single person who would, of course, have to be blind and stupid not to understand what was happening. The whole idea is that the victim does understand what is happening, that he cannot fail to understand. The objective is to make a show of intimidation, to spoil the day if not the life of someone you know to be a bad guy but who for one reason or another you cannot neutralize by the usual dirty tricks. Unless you want to keep this up for the rest of the subject’s life and bust your budget, the idea is to scare him so badly on day one that he’ll go into another line of work or flee the country

Old Boys, pp. 256-257

McCarry also uses the more familiar tradecraft term ‘dangle’.

A dangle, I should explain, is an operation in which one dangles somebody or something before an adversary in the hope that he’ll take the bait. If he does, benefits can be considerable.

Old Boys, p. 240

And McCarry’s discussion of such ‘dangles’ also references two of the real-world espionage cases most commonly noted in Russia-in-fiction spy novels — those of Aldrich Ames and Oleg Pen’kovsky.

If, for example, the infamous Aldrich Ames had been a dangle instead of a genuine rotten apple, he could have falsely identified the Russians’ best operatives as American agents and smiled while the Russians fed them into the fiery furnace. Instead, of course, he fingered actual American assets, and they were the ones who were cremated alive.

Old Boys, p. 240

Russia in Fiction has discussed the Ames case in our review of David Lindsey’s Requiem for a Glass Heart and the Pen’kovsky case —which is what lies behind the cremated alive motif— in reviews of James Barwick’s The Kremlin Contract and Owen Matthews’s Red Traitor.