The Russia in Fiction blog likes a good sub-genre. So how about, ‘books set in the Chernenko years’?

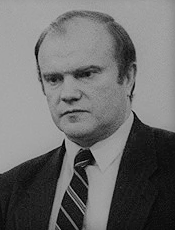

Except of course, Konstantin Chernenko was leader of the Soviet Union for so short a time that we can’t even talk about years. It would have to be ‘books set in the Chernenko year and 25 days’. He became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1984 and died in March 1985.

Après Chernenko, Gorbatchev et le déluge.

Paul Vidich’s The Mercenary, subtitled A Spy’s Escape from Moscow, is a terrific espionage thriller, that is not only set in early 1985 but is written in a style reminiscent of Cold War era spy novelists.

When Russia in Fiction rattles off its list of great Cold War spy novelists, it goes something like John Le Carré, rhymes with Charles McCarry, and add a couple of Bobs (Robert Littell and Robert Moss).

This is not a book blog that reduces novels to a 1 to 5 star rating as if there is some sort of competition. But these four, and with Le Carré in front, stand out. (The surname index takes you to three of these and will eventually review some classic Robert Littell too).

It seems that a few decades, even half a century, ago, was a halcyon period for the more literary espionage novel. With our country-specific focus, Russia in Fiction has also reviewed other lesser known authors from that time who fit into this category, notably Joseph Hone.

Paul Vidich, writing novels now in 2021, rings bells of recognition with regard to such writing. Partly of course, it helps that The Mercenary is set in the 1980s, but more than that, Vidich writes in the same thoughtful, intelligent way; he is unafraid of complexity of plot.

He even has his heroine, Natalya, name-check Le Carré. She is eating an improbably lavish meal in the Metropol Hotel with the novel’s hero, Aleksander Garin.

(Vidich gets Russia-in-fiction Brownie points for spelling Garin’s first name with a ‘ks’ and not an ‘x’. But loses them for perpetuating the apparently unshakeable, but mistaken, notion amongst Western writers and film-makers that Russians use the expression ‘na zdorovye’ as a toast, akin to saying ‘cheers’.)

Natalya flirts with Garin

she said that men only liked books by other men — Hemingway, or Tolstoy, or the Englishman le Carré

The Mercenary, chapter 12

As well as the fact that the Russia in Fiction blog loves a sub-genre, regular readers will also know that we have a slight obsession with book covers; specifically ‘silhouette, Red Square’ book covers. These have been massively overdone, and Russia in Fiction is a little aghast at the lack of originality amongst book designers that allows cover after cover after cover (and so on many times over the years) to be so predictable and almost identical. This will of course pass. In ten years time, and ever after, the silhouette cover will date a book as being from the early 21st century.

Yet, when it comes to The Mercenary, it was the ‘silhouette, Red Square’ cover that first alerted us to the book.

Why? Because it is one of the best covers of this type. It doesn’t just plonk a clunkily photo-shopped cut-out of a man onto the background of Red Square. Instead it seems to be a genuine photograph of a real person, dressed appropriately for a Cold War spy, walking down the cobbled slope in Red Square’s north-west corner, heading away from the square. No question but that he is about to disappear down into a metro station, probably heading to his left, through the gate into the Alexandrovsky Garden, before turning right a few hundred yards later and heading into the underpass towards the Lenin Library metro station.

The evocative cover prompted us to buy The Mercenary, but it is what is between the covers that made it a happy purchase.

******

As noted at the outset of this review, The Mercenary takes place at the end of Konstantin Chernenko’s brief tenure as leader of the Soviet Union. And explicitly so. The only other book that Russia in Fiction has so far reviewed within the ‘set in the Chernenko period’ sub-genre is Bart Davis’s Blind Prophet (1984); but that was published in that period and so was simply set in what was then the contemporary Soviet Union.

In The Mercenary, Paul Vidich has chosen this period for a reason. As he put it in an interview published earlier this month

The Soviet Union in the twilight of power struck me as a good place to set a Cold War novel. It was the moment when the country’s illusion of dominance met the grim reality of a crumbling system.

Tripfiction.com, 3 April 2021

As ever, Russia in Fiction asks two questions: what is the book like? And how does it portray Russia?

The Mercenary is a sophisticated and well-written thriller that draws the reader into its world in terms of both plot and setting. The set-up first chapter delighted us. It might seem a bit of cliché to start off with a CIA-KGB encounter in Red Square in the snow, but getting the central dynamic and location established from the off works well.

And the description is lovely, taking me back to one particularly memorable December night in the early 1990s when I walked onto a deserted Red Square’s vast cobbled expanse, as heavy snow fell, and was transfixed by the silence and aura of this historical site.

He moved clockwise around the medieval fortress and entered the open square, where the enormous clock and bells of Spasskaya Tower inside the Kremlin wall announced the time. A horizontal band of snow obscured the spire’s red star. Mueller saw the honor guard goose-stepping out of an archway in the wall, proceeding to Lenin’s Tomb on their hourly rotation.

The Mercenary, Chapter one

Such is the first of several well-drawn Moscow settings.

(Though, for those of us who know and enjoy the poetry of Philip Larkin, the phrase ‘enormous clock and bells’ cannot help but bring to mind Larkin at his lewdest, in the poem Sunny Prestatyn. Did Paul Vidich have the same allusion in mind?)

At various points in The Mercenary we are taken to Vvedenskoye Cemetery, an apartment on Kutuzovsky Prospekt, Kropotkinskaya Metro station (another favourite of mine), and Sokolniki Park.

Garin, a CIA man of Russian parentage, is inserted into Moscow and tasked with bringing out a Soviet official who has been spying for the CIA. This plot line, which runs from beginning to end, is supplemented by Garin’s relationship with Natalya, the daughter of a Soviet General killed by the authorities for likewise working on behalf of the Americans.

To add to the tension, the General was caught by the KGB just as the CIA tried to get him over the border to safety in an extraction plan that Garin had thought secure. Can he get their agent out of the Soviet Union safely this next time? Is there a leak in the US Embassy? Can he trust Natalya? These are the questions that drive the narrative.

Paul Vidich, wittingly or not, follows in the footsteps of several other authors by giving some characters the same name as well-known Russian political figures.

The General’s surname is Zyuganov. Fine for the ninety-plus percent of readers who may never have heard of the Russian Communist Party leader, but a little distracting for those of us who have.

Vidich has done his research, and incorporates familiar Cold War spy novel tropes. The KGB deploys ‘sparrows’, female agents who use sex to entrap their targets, and metka, a powder of nitrophenyl pentadienal known as ‘spy dust’ and used to track people. There are arrests, interrogations, double-agents, shootings, and the classic denouement at a border crossing point.

But Vidich is not merely ticking off the tropes. He applies colour and originality, not least in that the crossing point in the penultimate chapter is on the border with Czechoslovakia, allowing some exploration of the far from simple relationship between the Soviet authorities and their Czech allies. Nor is the novel’s ending easily foreseen, coming as it does with a measure of the nuance found more often in Cold War espionage novels of a few decades back than in what tend to be the more formulaic preferences of our day.

To finish this review where we started it, The Mercenary takes the reader to a world that is coming to an end; the political landscape of the Soviet Union is shifting.

‘Chernenko is dead. The news will be in tomorrow’s papers … the Soviet Union of Brezhnev and Khrushchev is dead. Chernenko was the last Bolshevik — elderly, dull, uninspiring, the personification of decay. He has been sick for years. The surprise is not that he is dead but that it took him so long to die.

He could barely stand at the podium to read his eulogy of Andropov last year, and when he finished two bodyguards helped him from the stage. He was a chain smoker and a drunk, and he suffered from cirrhosis and heart disease, and who knows what else. He was a stumbling example of the Soviet Union. Now he is dead. His death will be announced on page two of tomorrow’s Pravda. Gorbachev’s ascension will be on the front page. He will be making changes’.

the Mercenary, chapter 12

Pedantic to the last as Russia in Fiction is, let us note that of course Chernenko’s death was on the front page of Pravda on 12 March 1985.

But it was clear from the picture and the three-word headline ‘Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev’, that although in the bottom right hand corner of Pravda’s front page, it was Gorbachev’s accession to the position of Soviet leader that was the big news.

Quite how big that news was to turn out would have been beyond comprehension back then. Within a little over half a dozen years not only would Gorbachev no longer be leader of the Soviet Union, but there would be no Soviet Union left to lead.

Après Chernenko, Gorbatchev et le déluge.