Crime not espionage, that was the trend for thrillers about Russia in the 1990s, as the Russian state all but collapsed and Russian criminal gangs made their presence felt across the globe.

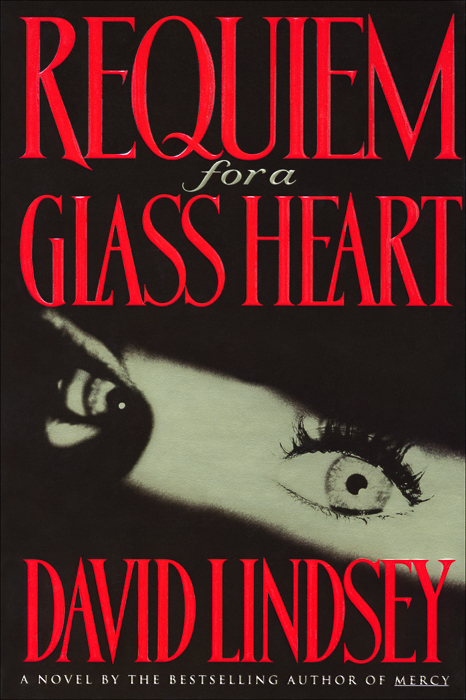

David Lindsey’s Requiem for a Glass Heart is very much a thriller —a terrific read, combining a page-turning plot with a layered development of character and situation.

Plot-wise there are two central female characters, introduced one at a time in their particular situations before these situations merge as the novel reaches its climax.

One of these characters, Cate Cuevas, is an FBI operative in a state of emotional agitation, having lost her husband and fellow FBI officer ‘in action’ and later discovered him to have been known by most colleagues, but not by her, as serially unfaithful.

The other lead character, and the more interesting from the Russian perspective, is Irina Izmaylov (not, unfortunately, Izmaylova) — a skilled Russian assassin working on behalf of a criminal boss, Sergei Krupatin.

Like the assassins in Clifford Irving and Herbert Burkholz’s The Death Freak (1979), Izmaylov’s killings are expertly crafted, drawing on detailed knowledge of the victim to devise a death that is hard to pin on anyone.

As Requiem for a Glass Heart progresses, the complex motivations, foibles, and talents of these two central characters are drawn out. Izmaylov’s mafia boss Krupatin seeks to expand his criminal empire in the United States, taking on the Italian mafia and Chinese organised crime groups. Alongside the pleasingly original plot, Lindsey writes some terrific set-piece scenes of assassination, infatuation, and manipulation. At over 600 pages, the book grips all the way through.

And the Russia-in-fiction elements? In terms of location, most of the story is situated in the regular settings of David Lindsey’s dozen or so thrillers, Texas (Houston to be precise) and Mexico. But the novel starts in St Petersburg, and roams across the globe, to London, Paris, and Italy.

The cover of the original edition, at the top of this post, was replaced later with a different one, emphasising that this is a Russia-related thriller.

David Lindsey’s set-up for the plot involves a fair amount of exposition —usually done via the time-honoured and effective thriller method of a character providing a briefing for colleagues that at the same time gives the reader the requisite historical and political knowledge to get what is going on. The account of the development of Russian organised crime beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union in the 1990s is accurate and well-told.

‘Car thefts exploded.’ Jaeger shook her head. ‘You can drive to Moscow in twenty hours from Berlin. That first year, twenty-four thousand Audis, Mercedes Benzes, and BMWs made the trip out of Germany going north. Within a few years the car thefts were up to a hundred and thirty thousand annually. It was absurd’.

requieM for a glass heart, p. 82

The account develops into a description of the various criminal groups expanding out of Russia, and how their techniques differed from established West European groups. Essentially, they were even more brutal. Fictional crime boss Krupatin is portrayed as a combination of sophistication, intelligence, and ruthless evil. And he loves London, as was the trend with super-rich Russians in the mid-1990s.

Krupatin’s rise dates back to the 1980s. As the Soviet system gave way to corruption and collapse, he gains government licences, becomes an importer of scarce goods, and — in the graphic language of the briefing

because of his government connections, he was standing in the doorway of opportunity when perestroika walked through …

Black and grey money flooded into joint ventures with Western entrepreneurs …

During the six years of perestroika Krupatin became a criminal giant …

In August 1991, the Soviet Union fell apart. Fifteen new nations emerged, and the criminals really went to work. Russia was like a helpless woman being gang-raped by her own children .

requiem for a glass heart, pp. 102-103

And so the briefing goes on. We are told of drug deals, the capture of Russia’s natural resources, the sale of arms by corrupt and poverty-stricken army officers. Krupatin makes contacts with the Sicilians. His drug profits quadruple. His organisation operates throughout Europe and into the United States. His operations are conducted by ‘Chechen thugs’. Krupatin by now sits above this, overseeing his lieutenants, making sure all is running well.

If it isn’t, people die

requiem for a glass heart, p. 105

Lindsey’s observations of Russia set the scene well, and point up factors that were coming to be noticed in the mid-1990s, and were to become increasingly important in Russian life in the years after this novel was published.

He notes, for example, that many of those involved in Russian organised crime had previously worked for the KGB. When the Soviet state collapsed, they gained lucrative work, using the skill-set that they had developed on behalf of the state, except now deploying it to greater personal profit in a different international setting.

As the plot comes to a climax, Krupatin appears to have a team of skilled operatives working for him to dodge the FBI net that is closing in. Leo Ometov, a Russian police officer working with the FBI, warns his Amerian colleagues

You are working against people who used to be with Soviet intelligence. Some of them used to be Soviet intelligence. Do you want to think about that? How did your country fare in that little contest? These are the people who turned Aldrick Ames and assassinated ten of your agents. We bankrupted an entire society to train these people. The social system did not survive, but these people got the best education imaginable in deception, and they did survive. These are not just gangsters you are dealing with here, my friend. These are people who used to manipulate a nation. And now, as criminals, still do.

requiem for a glass heart, pp. 425-426

Insight and phrasing of this calibre marks out Requiem for a Glass Heart as more than your average crime thriller in terms of its knowledge of Russia. It is an impressively written and expertly plotted story, and stands high in my often used ‘how come I had never heard of it before I found it in a second-hand bookshop?’ ranking.

The Aldrich Ames case has been the subject of multiple books, and the name-checking in Requiem for a Glass Heart is by no means the only such reference in Russia-in-fiction novels. Ames’s treachery is an important plot device in Frederick Forsyth’s novel Icon, also published in 1996.