Here at the Russia in Fiction blog, we are interested in how Russia is portrayed in English-language fiction. Whether that fiction is any good comes into the reviewing too of course, but the tropes and plot devices and imagery and assumptions of a remaindered thriller can still fascinate as insights into popular perceptions of Russia at any given time.

James Steel’s December serves as a great example for taking the ‘how Russia is seen’ temperature. From title and front cover blurb, at the end of this century’s first decade, that temperature is low.

A NEW COLD WAR HAS HIT EUROPE …

dECEMBER, jAMES STEEL

In December we have the common features of middle Putin-era Russia-related thrillers —oligarchs, a hard-line president, and Russia returned to its position as the West’s main enemy. There are the inevitable references to Aleksandr Litvinenko, with Steel’s oligarch characters drinking a cocktail by that name and proudly proclaiming that it doesn’t contain Polonium-210 (p. 28). There are the inevitable references too to murdered journalist Anna Politkovskaya (p. 280).

And —joy of joys!— even the cover picture fills the standard requirements.

Red Square — tick.

Snow — tick.

And running figure in silhouette — tick.

What is it with book covers and silhouettes? (As discussed with plenty of illustrations in this post here).

Browsing in a remainders’ shop almost a decade ago, I came across two recent Russia-related thrillers that I had never heard of —one was the book under review here, James Steel’s December (2009), and the other was Ted Bell’s Tsar (2008). James Steel is a British thriller writer who later switched to the fantasy genre. As a thriller writer he deserves better than to be a relative unknown relegated to the remainder shelf.

December is a cracking thriller. For sure, it is not in the very top rank, but it delivers a decent yarn and, from the Russia perspective of interest here, is pleasing in its understanding and detail.

And just to back up my notion that even remaindered thrillers tell us about the Russia-related zeitgeist, Tsar and December, published a year apart as they were, have a lot in common.

Both these thrillers present us with a rugged, British, former military hero on whose mission to Moscow the future of the Western world depends. Steel’s hero goes by the name of Alex Devereux. Both these books are also set in that ‘near future’ beloved of thriller writers, which allows them to extend present trends just a little further to create crisis. Both have a Russia ruled over by a post-post-Putin figure. Both these books also make the president a malevolent, slightly mad, figure who harks back to the Soviet years, re-opens the Gulag, and has opponents killed.

In December, Russia’s president —Viktor Krymov— came to power after President Dmitrii Medvedev had gained a second term as president in competition against Putin. So it is set after 2012.

The liberal Medvedev had himself been deposed in a palace coup by Krymov, who, unsurprisingly, is a hard-line figure, suspends the constitution, declares himself president for life, and oversees the rapid deterioration of relations with the West.

Why do the Russian presidents put in place by thriller writers never come from the liberal democratic camp? (That question was rhetorical …)

Steel’s plot hangs on Russia using its position as Europe’s chief source of natural gas as a policy tool. It begins atmospherically, in the eponymous December during which all the action occurs, with London in darkness caused by power-rationing. Every street is dark, every house lit only by candles, except that is for the house of Russian oligarch, Sergey Shaposhnikov, apparent friend of President Krymov but in fact flawed hero of the book and secret opponent of the president.

Steel’s conceptualisation of Russia is relatively sophisticated. He puts forward—through the mouth of his oligarch character— the idea of the 1990s as a time of chaos, with Putin restoring order, but pulling away from democracy. Such a system, balancing the factions of the executive against each other, is said to have brought stability when you have

an intelligent guy like Putin who can actually balance factions

But without Putin

the factions in the Kremlin are like lions fighting over a kill

December, james steel, p. 37

Steel introduces too, in entertaining fashion, the concept of the resource curse; that abundance of natural resources removes a country’s incentive to develop its economy.

‘we just dig a hole in the ground and the money pours out. Basically we’re just a petro-state in the same way as any other Third World dictatorship. It leads to what I call the gangsterisation of the economy. You have an FSB man on the board of all major companies. Now these guys are good at wiretaps, surveillance hits —they can do that— but can they read a balance sheet? Do they have a feel for a market? Can they organise a supply chain? The f*** they can! They’re hoods, spooks! … We’re a f***ing banana republic run by goons!’

december, james steel, p. 39

Steel uses his oligarch character to run through a list of problems facing Russia which is familiar to anyone who knows the speeches of President Medvedev, and before him President Putin, in the first decade of this century: the need to modernise, the dangers of demographic decline, and the benefits of foreign investment.

Shaposhnikov the oligarch talks knowledgably too about Russian literature and develops the familiar idea of the Russian soul and its spiritual and emotional essence apparently unmatched in and never understood by the materialistic West.

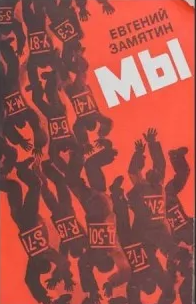

Shaposhnikov loves Russian literature, notably Chekhov and, impressively, Zamyatin’s We, which he notes as the inspiration for Orwell’s 1984. In fact, more than the inspiration

the f**ker ripped off the plot completely (p. 76).

december, james steel, p. 76

There is too a love interest, the stunningly beautiful Lara from Voronezh; a city I know well, having lived there for some months during the Soviet era.

The plot of December involves Devereux and a team of mercenaries, supported by Shaposhnikov, going into Russia to rescue a well-known political prisoner from a labour camp in the Chita district —a camp based on that where imprisoned oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky spent much of his sentence. (And while I am place-name dropping, I spent a few weeks near Chita district one weird summer back in the 1990s too).

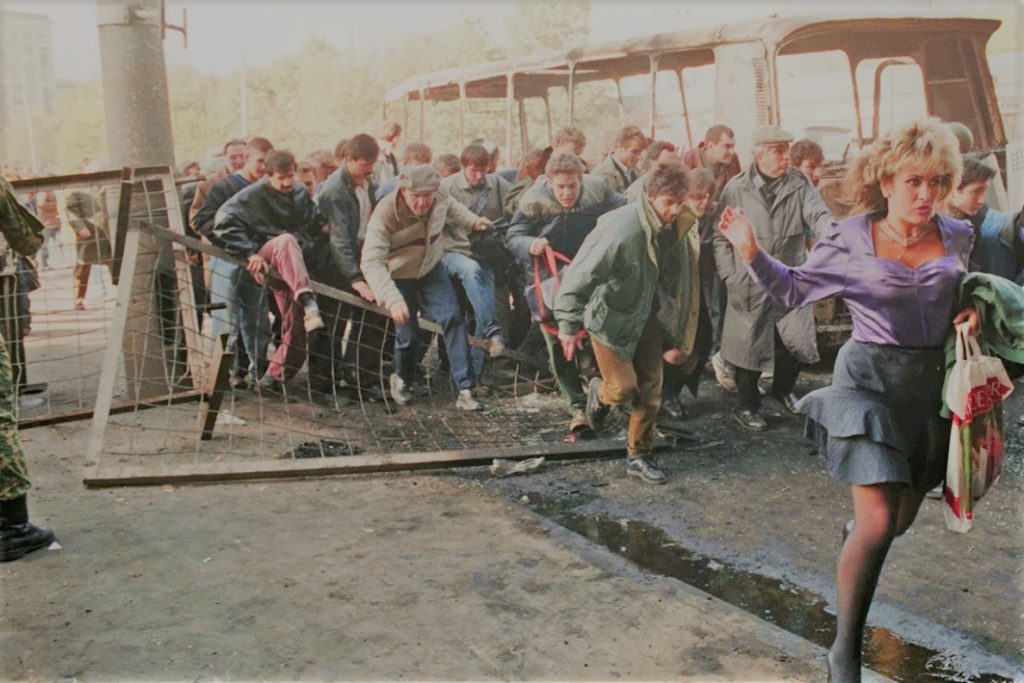

The plot premise is that this prisoner —a former successful captain of the Russian football team and hence a national hero— will be the figurehead for a swift coup in Moscow to depose the increasingly mad and bad Krymov. The key will be to broadcast to the nation from the Ostankino TV tower, a Moscow landmark which was the scene of a brief but crucial firefight between pro- and anti-Yeltsin forces in the struggle between president and parliament in 1993. Steel makes this historical reference, but gets the year wrong (p. 62).

He gives the correct date in his afterword, but there wrongly identifies the White House in Moscow as ‘the presidential palace’, when in fact it was the Russian parliament, and —as such— the stronghold of President Yeltsin’s opponents (p. 456).

This typically pedantic Russiainfiction.com carping about details aside, the thing with December —and perhaps the reason why I found it in a remainder shop rather than seeking it out myself— is that it is a book of two halves.

Most of the content of this review comes from the first half of the book, where the plot is set up and an array of ideas about Russia is brought in and discussed.

The second half is much more of the ‘flash bang’ genre —a series of military set-pieces as Devereux and his crew engage in a rescue mission in Chita oblast and then street fighting in Moscow. It is done well, and in fact some of the detail of the street fighting and its awareness of the geography of Moscow is impressive, but there is not much more to it than flash bang, with a little bit of the recurring love story thrown in.

Mind you, flash bang, marauding through Moscow, and love interest involving the beautiful Lara from Voronezh, is not, on reflection, too bad a way to chill out with a genre-typical Russia in fiction thriller.