It is a happy coincidence that the Russia in Fiction blog is being written at a bumper time for Russia-in-fiction trilogies. We are in the middle of those by Sarah Armstrong and Ben Creed. The final one of Henry Porter’s Paul Samson series was published in April of this year, followed the next month by the last in Tom Bradby’s Kate Henderson series (the first is reviewed here, the third is mentioned here). And we are certainly at the end of the Dominika Egorova trilogy by Jason Matthews, as he sadly passed away a few months ago (again, the first is reviewed here).

And now his namesake Owen Matthews brings us the second in his Alexander Vasin series.

Red Traitor differs from the first novel in the series, Black Sun (2019). Black Sun was very much a detective story, and notable for its plot being contained geographically and culturally in the distinctive and little-known world of the Soviet closed city.

Red Traitor ranges more widely. In genre terms Red Traitor moves onto the ground of the international relations thriller, with sonar-pinging echoes of Tom Clancy’s early work.

Set during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962, Red Traitor really has two heroes. KGB Colonel Alexander Vasin —the series hero— is on the Moscow counter-espionage beat, netting an American spy in the Soviet military intelligence service, the GRU. Meantime, Captain Vasily Arkhipov is at sea, commanding a group of Soviet submarines, equipped with nuclear weapons, heading for Cuba.

Captain Arkhipov is one of several real life characters to appear in Red Traitor, and there are others —as the lengthy Author’s Note at the end of the book sets out— who are loosely drawn on the lives of real characters.

Like Black Sun, Red Traitor deals with the world-threatening power of nuclear weaponry, and the particularly dangerous period of the early Cold War when the USA and the USSR were developing both technology and military doctrine, testing each other’s responses, and moving with the reckless caution of a tightrope walker towards that point of dangerous equilibrium where the world eventually settled for a couple of decades or more.

Black Sun was set in 1961, as the Soviet Union’s Tsar Bomba test caused the largest explosion ever created by humankind. Red Traitor takes place a year later, in October 1962, as the Cuban missile crisis threatens the world with a nuclear World War III.

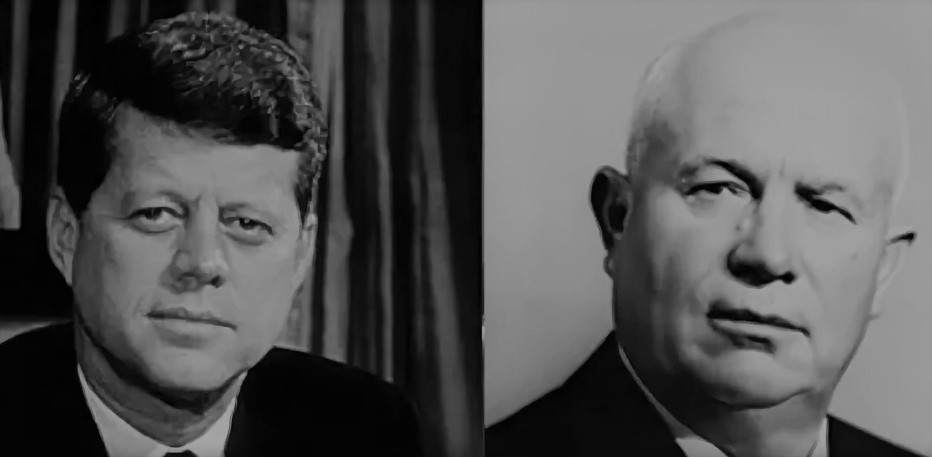

The Vasin and the Arkhipov plot strands are set, respectively, in different key elements of the Cuban Missile Crisis — away from the high-level Kennedy-Khrushchev decision-making, but each of immense significance during those weeks.

Colonel Vasin —an entirely fictional character, lest you’re losing track— is charged with successfully closing the case of GRU officer, and suspected American spy, Colonel Oleg Morozov.

Morozov is a version —Matthews calls him the ‘dark twin’— of real-life American spy Oleg Pen’kovsky.

(Russia in Fiction has noted the Pen’kovsky case in our review of James Barwick’s The Kremlin Contract).

The Vasin plot takes place in Moscow and so is the strongest Russia-in-fiction strand.

Captain Arkhipov —a real-life figure who incidentally died on this very day 23 years ago— is the flotilla commander in charge of four Soviet submarines, each armed with a nuclear torpedo for potential naval warfare purposes. Use of these weapons is at the discretion of each submarine’s captain; an extraordinarily onerous discretionary burden exacerbated by the lack of knowledge of how the crisis was developing. (A version of this scenario may be familiar to film lovers in the 1995 movie Crimson Tide).

Owen Matthews writes a mean thriller. On the submarine side of things, he has the detail down to a tee. Or at least he seems to and sounds convincing; Russia in Fiction has no idea about such things.

A second ping, fainter than the first, rang through the boat.

The indicator of the shallow depth gauge fluttered to a stop on its maximum setting – sixty meters. The deep diving gauge crept on through eighty, then a hundred meters. The midshipman at the diving controls, sweating with concentration, pulled back the forward and aft diving fins while his colleague ducked back and forth along a bewildering array of taps to even out the water in the ballast tanks. The depth indicator settled neatly on 120.

Red Traitor, Part Five, chapter two

Where Russia in Fiction does have a clue is when it comes to the portrayal of Russia. And Owen Matthews —the son of a Russian mother who lived in the Soviet Union during these years, and himself having made a career as a journalist and writer in post-Soviet Russia— leads the way in terms of accurate portrayals of Soviet Russia in English-language fiction.

Many a writer of Russia in fiction feels obliged to craft a banya (bath-house) scene. But none nails it quite like Matthews.

Colonel Vasin delivers vital information to KGB General Orlov.

Orlov beckoned Vasin to follow. The pine-planked Russian sauna had been heated to an infernal temperature, which Orlov made even more unbearable by scooping a wooden ladle full of water and tossing it on the iron furnace. Vasin had always hated the gruff physicality of the banya, the appalling heat and pouring sweat of it. Orlov settled heavily on a tiered bench, his muscular thighs spreading on the hot boards. Vasin struggled to keep his mind focused as the steam heat rose.

… “A flotilla of submarines has been dispatched from Severomorsk to Cuba. … The fleet has been armed with nuclear torpedoes. … The commanders were given individual authority to use their nuclear weapon if attacked.”

The General said nothing. Both men were turning bright pink in the fierce steam heat. They both sat, heads down and elbows on knees, with the dripping sweat evaporating from the floorboards as fast as it fell.

“Sorry, sir, I must…”

Vasin stumbled out of the banya into the relative cool of the dressing room. The attendant pointed to a doorway that led to a large, marble-lined plunge pool. Vasin always hated this part, too. He took a breath and stepped in, the freezing water scorching his skin and rendering him numb with shock.

Red Traitor, Part Four, Chapter 11

In a similar fashion, Owen Matthews takes the reader to another place which appears regularly in Russia-in-fiction thrillers; and again he manages to move beyond the familiar clichéd descriptions. That place is the Lubyanka, the KGB headquarters in central Moscow.

Many a Russia-related thriller drops in to the Lubyanka and goes underground to its dark network of cells where brutal interrogations and summary executions take place. Almost as often, writers will make reference to the fact that before the Revolution, the large building used to be the offices of the All Russia Insurance Company, and that in the Soviet years a statue of Felix Dzerzhinskii, the founder of the Soviet secret police, stood on a plinth outside, before its removal in anti-Communist protests in 1991.

In Red Traitor, Owen Matthews eschews such standard boilerplate descriptions and actually tells us stuff that Russia in Fiction did not realise but that rings true.

As the novel heads to its conclusion, Colonel Vasin is on the run from his superior and makes the counterintuitive decision that the best place to hide is within the Lubyanka itself.

If he refrained from trying to enter any restricted area or sign out any document from the registry, Vasin realised that he could live, sleep, eat, maybe even bathe in the Lubyanka for days, undetected. Weeks, maybe. Unless of course he bumped into Orlov himself, puffing down the corridors of the labyrinth like a hungry and furious Minotaur.

…

“I’m living rough in the corridors of the Lubyanka. Haven’t found the barbers yet.”

“No? There are two. One by the North prison barracks, first basement level. And a posher one in the annex on the other side of Pervomaiskaya Street, the department that does disguises. There’s a tunnel …”

“Thanks, Vadim, for the grooming advice.”

…

The kontora annex that stood on the opposite side of Pervomaiskaya Street was sarcastically known as the Artists’ Wardrobe. Vasin had never been there himself but knew that it specialised in costumes and disguises for covert surveillance.

…

“Department you looking for?”

…

“Barbershop.”

“Ground floor. Left down the corridor. Stinks o’ perfume. Can’t miss it.”

…

He passed open doors which revealed a seamstress’s station, fitting room – and an atelier equipped with rows of mannequin heads, each with a wig on it. Vasin paused and peered inside. A girl in civilian clothes was laboriously brushing out a long, blonde wig. She looked up, startled by Vasin’s intrusion.

“Can I help you?”

“Uh. Yes. … Can I look out of your window? Yuri Gagarin is about to drive by.”

“Wow! Gagarin! No way!”

The young woman jumped up and ran to the window, hoisting herself up on the sill with her hands in girlish enthusiasm.

Vasin sprinted down the corridor, cramming his stolen wig on his head.

Red Traitor, Part Five, Chapter 10

When he eventually does get round to describing where a prisoner is held in the Lubyanka, originality is again Matthews’s forte.

Famously, no man had ever visited every corner of the vast Lubyanka complex. Certainly, very few people had ever found their way to Special Repository 9/84. The small suite of rooms was, unlike all the other prison spaces of the Lubyanka, actually on the ninth floor.

Red Traitor, Part Seven, Chapter 4.

Russia in Fiction is loving this level of detail, which the Moscow strand of Red Traitor displays. And not least in its descriptions of Moscow’s streetscape. So good to read an author who knows which metro stations are nearest to which locations, and how long it takes to walk between them.

And if you think car chases only work in the movies, try reading Red Traitor’s last-chapter description of the same around the centre of Moscow in 1962, as Vasin’s Moskvich tries to evade a KGB Volga.

Red Traitor has a different vibe from its predecessor, Black Sun. As with all the ongoing trilogies noted at the start of this blog post, threads run through the earlier books that seem to have sufficiently little to do with the volume in question that Russia in Fiction presumes their purpose to be to line things up for the finale. That being the case, we look forward to how the third Colonel Vasin book deals with Vasin’s domestic arrangements of alienated wife and a son approaching adulthood, and what nuclear-related events await Vasin in his next assignment as the commander of a penal colony in Siberia.