Part two of this review is here.

‘It’s all right, Martha. You’ll find where you’re supposed to be.’

I spoke into my hands. ‘I’m supposed to be in Moscow. I love it there and there’s so much I didn’t see. I was waiting for the snow.’

The wolves of leninsky prospekt

The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt might dip into the world of Cold War tensions, surveillance, and espionage, but it is no spy thriller. Rather, Sarah Armstrong crafts a deceptively deep tale built around the fraying gender-based constancies of 1973.

As the novel opens, second year Cambridge student Martha —whose father is a senior civil servant doing ‘who knows what, at GCHQ, Government Communications headquarters’— is handing out leaflets outside Trinity College, calling on the College authorities to ‘stop economic and sexist exploitation’ and admit female students.

Martha’s actions, coupled with unspecified ‘previous warnings’ are enough to get her sent down.

Stuck back in her parents’ convention-bound village home over Christmas 1972, and faced with a stiflingly parochial existence stretching into the future, Martha and her childhood friend Kit, a homosexual junior diplomat with a posting in Moscow, hit on the idea of getting married.

This deliberately sham marriage suits Kit, as a way to bolster careerist credentials in an era when being gay was seen as something to keep quiet about. And it suits Martha, offering an escape from the stultifying parental proposal that she teach in the village primary school.

Not that the novel’s set-up is so starkly presented as that summary suggests. Martha is no out-and-out radical bent on rebelling against her upbringing. It is vaguer than that. She thinks things need to change and has an instinctive willingness to act, whilst still being concerned to somehow behave correctly and find her way in the world as it is.

In The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt, the early 1970s competes with Moscow for the role of ‘setting as character’. From the Russia-in-fiction perspective, it is when these two combine that the novel really flies.

Martha’s preparatory reading gives her —and the reader— the straightforward politico-historical basics.

Leonid Brezhnev was in charge, and things were pretty stable. People had money, if little to buy, free education and health, zero inflation, no unemployment and no crime. Supposedly.

the wolves of leninsky prospekt

Some of the standard things a Westerner notes when living in the Soviet Union find their appropriate place in Sarah Armstrong’s writing, such as when Kit takes Martha for a meal in the Metropol Hotel, and helps her out with ordering:

‘When the waiter comes back, I’ll ask him to point out what they actually have in. Whenever I choose from the menu, they don’t have it. I started to take it personally until I realised that the menu is more of a wish list.’

the wolves of leninsky prospekt

A recurring motif is that for all its achievements, the Soviet regime is not like the West. Martha, as most Western travellers to the Soviet Union, has been warned to watch out for Soviet eavesdropping —electronic or human— on conversations. Sitting with Kit in the restaurant, she asks him:

‘So, we’re OK here? To talk?’

‘Martha, you’re going to drive yourself mad if you keep thinking about things like that. That’s for me to worry about.’

…

He was right. I was overthinking things again. Everything I’d ever heard about Russia, without even being aware of it, had been circling in my head. Parades of guns and rockets, the tales of Siberia and starvation and murder.

the wolves of leninsky prospekt

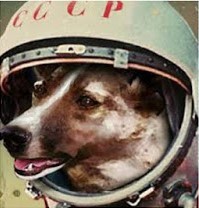

But as the novel progresses, Kit’s early reassurances seem fake. In their celibately conjugal apartment, he has put a poster up featuring a man and a dog, both wearing helmets, with a Sputnik spacecraft behind them.

Kit explains:

‘I want you to enjoy it here, Martha, but I don’t want you to be deceived. There’s a reason I put that poster up.’

I thought of the poster, man and dog, dreaming of the stars. ‘The astronaut?’

‘Cosmonaut. It’s to remind me that I’m dealing with the kind of bastards that would shoot a dog into space to die. If it’s beautiful here, it’s for show. For every palace for the people, there’s a gulag in Siberia. Don’t forget what they’re hiding.’

the wolves of leninsky prospekt

The combination of temporal setting (1973) and physical setting (Moscow) works well most of the time. Metro stations and streets carry their Soviet era names.

There is reference to the 1973 Universiade, held successfully in Moscow and seen as an important staging point for the Soviet Union to be awarded the 1980 Olympic Games (the negotiations for which are set out in the opening chapter of John Salisbury’s Moscow Gold).

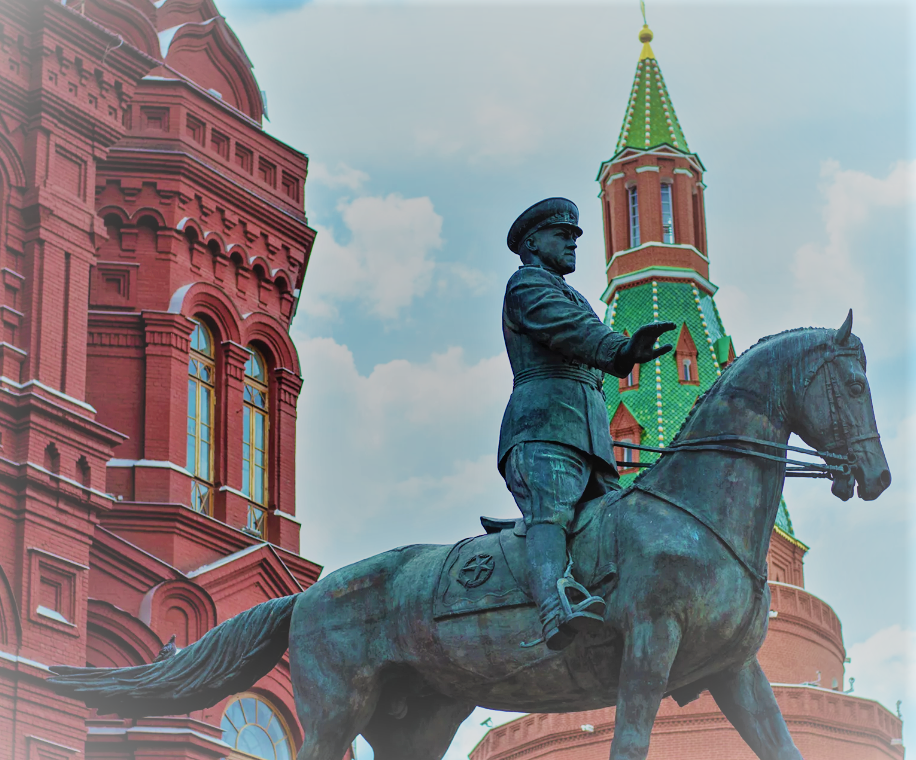

But there does seem to be an anachronism in the chapter where Martha exits the Prospekt Marksa metro station (now Okhotny Ryad) and walks up the grey cobbles onto Red Square between the State Historical Museum and the Kremlin Wall, having seen en route the ‘statue of a man on a horse’. Presumably a reference to the statue of Marshal Zhukov now standing in that position, but erected in 1995.

And yes, such anachronism-spotting might be standard Russia-in-Fiction blog pedantry, but hey, we are all about how Russia is portrayed in fiction here.

And a further excuse in this case comes from a meet-up with a Russian acquaintance in 1999.

‘Where shall we meet?’

I suggested the statue of Marshal Zhukov next to Red Square, assuming that my Muscovite friend would be familiar with so central a landmark.

‘The what? Who?’ she replied.

‘You know, the famous Soviet general? His statue. Next to the Kremlin, on the way to Red Square.’

Neither Zhukov nor this statue had yet come to the awareness of my well-educated Russian associate. In the end, in exasperation, I told her to walk out of the Aleksandrovsky Gardens at the Red Square end and look straight ahead for the ‘man on a horse’.

Ever since then, Marshal Zhukov has always, in my mind, been the ‘man on the horse’. Out of time it may be, but the use of that very phrase in The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt delights this reader.

That glitch aside, the Moscow landmark count delights with its niche originality, for example, reference to the Khudozhestvenny cinema (‘Built in 1909, would you believe’) and its adjacent metro station (Arbatskaya).

Of which Kit says

‘Yes. It’s one of my favourite buildings.’

I stood back. ‘Mempo’. I still had to try to read in English first, knowing full well that I couldn’t.

‘It’s a Metro station?’

‘One of the best. It’s even more amazing inside’.

the wolves of leninsky prospekt

I concur with Kit. And these adjacent buildings bring back personal memories of Moscow opening up in the early 1990s, with rival football fans revelling together in and around the bars on New Arbat street just across the road from here.

Part two of this review is here