Published in 1989, but set a decade earlier, as Jimmy Carter’s presidency is coming to an end and the Soviet Union seems as threatening as ever to the West, The Romeo Flag flew briefly in the world of Russia-in-fiction thrillers.

The Romeo Flag offers a complex globe-trotting, decade-spanning, page-turning plot that differs from the run-of-the-mill, even whilst being built around a couple of the staples of Russia-related fiction; a surviving Romanov heir and a Soviet mole at the heart of the US government.

On top of that, The Romeo Flag turns out to contain uncanny parallels with a fresh new soon-to-be bestselling novel published only last week.

Although a relatively prolific author (most often as half of a writing duo, with her husband, calling themselves John Case), Carolyn Hougan did not specialise in writing about Russia. Russia in Fiction only chanced on this novel by spotting its part-Fabergé egg, part-Matrioshka doll cover whilst browsing a second-hand stall. We are glad we did.

Wandering along the Charing Cross Road in central London one winter’s day in early 2018 —having just confirmed with disappointment that on the site of the famous old bookshop at number 84 there now stands a branch of McDonalds— we spotted a small row of paperbacks lined up outside one of the remaining second-hand bookshops on that busy road. These weren’t even in the shop. They were the ‘so cheap that we don’t really care if they’re stolen’ overflow stock. A practised eye had little trouble in skimming the few dozen tatty spines and spotting, with some pleasure, two Russia-in-fiction thrillers (Soviet-era, to be precise) written by authors of whom Russia in Fiction had never heard. Fifty pence each.

One of them was Moscow Gold by John Salisbury, the other The Romeo Flag, by Carolyn Hougan (1943-2007). It is over 400 pages of superbly plotted ‘who is the mole?’ espionage thriller.

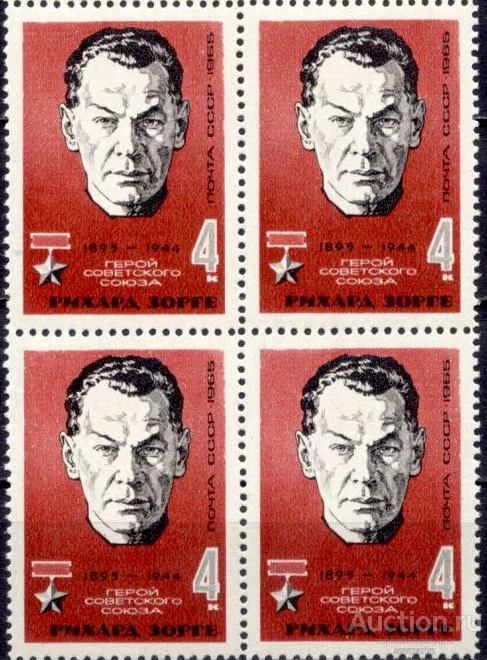

Set in the United States, its premise is that the Richard Sorge Soviet espionage ring in the Far East during the 1930s spawned a Soviet agent who made his way into the highest echelons of US power by the 1970s.

The novel’s heroine, Nicola Ward, an everyday schoolteacher living in Maine, unexpectedly receives a trunk full of family heirlooms, documents —and priceless treasures including a Fabergé egg. She hires a washed-up ex-CIA Russia specialist to help her translate and authenticate. Then all of a sudden, there seems to be a price on her head, as the investigations begin to reveal a decades-long Soviet plot to penetrate the US establishment, and to hint that Nicola herself may have Romanov ancestry.

The plot of The Romeo Flag is complex but clear. Russia in Fiction must confess to usually finding ‘Romanov pretender’ story lines tedious, but in this case it is both well done and not at the forefront of the story. There are strong lead characters, a developing love story, and some top-notch genre scenes of violence, chases, tradecraft, and so on. There is even space at the end for an interesting, and convincing, dialogue on the nature and purpose of spying.

Little of The Romeo Flag is set in the Soviet Union, with the exception of a diary written by a servant of the Romanovs during their last days of captivity. There is not much scope here for a critique of the author’s handling of Soviet life or the Russian language. The main Russian characters, the KGB, are pretty much straight-down-the-line uncompromising, efficient, and dangerous.

One strange aspect that fascinates and bears noting, however, is the existence of uncanny parallels between The Romeo Flag and a new novel, by a bestselling British author, published only a week before this review was posted.

Let us set the scene. It is always a little intriguing when novels sometimes decades apart have names and circumstances that echo one another. Russia in Fiction has noted this before in its review of the The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt (2019). Sarah Armstrong’s novel has as its central first person narrator a young woman, by the name of Martha, living in Moscow because her husband works there and meeting an enigmatic older English émigrée by the name of Eva.

Alice Jolly’s If Only You Knew (2006), written more than a dozen years earlier, has as its central first person narrator a young woman, by the name of Eva, living in Moscow because her husband works there and meeting an enigmatic older émigrée from England by the name of Maya.

To be clear, there is no suggestion of anything nefarious or plagiaristic here. The novels are entirely different. But their parallels in set-up and nomenclature give pause as to the nature of coincidence or subliminal nudges or perhaps simply the writer’s art.

Strangely a similar set of parallels cropped up just as Russia in Fiction was preparing this review of The Romeo Flag (1989).

We had spent a pleasant few hours reading Triple Cross, the just published final instalment of Tom Bradby’s ‘Russian mole in the UK political establishment’ trilogy. (Russia in Fiction has reviewed the first of these three novels, Secret Service.)

In Triple Cross (2021), the novel revolves around a female lead character, separated from her husband and living with an anorexic teenage daughter, engaged in the hunt for a Russian agent deep in the heart of the British establishment, code-named Dante.

In The Romeo Flag (1989), the novel revolves around a female lead character, separated from her husband and living with an anorexic teenage daughter, engaged in the hunt for a Russian agent deep in the heart of the American establishment, code-named Dante.

Again, to be very clear, there is no suggestion of anything nefarious or plagiaristic here. The novels are entirely different. And in this case are separated by more than 30 years. Dante makes for a good code-name. The development of a female lead character through exploration of post-relationship breakdown parenting problems adds depth and protects these novels from the formulaic.

It was weird though that Russia in Fiction, before we had realised any parallels, should choose to read Triple Cross on the day we had already decided to publish a review of The Romeo Flag.