Hey, this is the Russia in Fiction blog — what’s with The Starlings of Bucharest? Have we gone all Romania in Fiction? Now that would be a struggle to get to our 100 reviews …

Well, rest easy. The Starlings of Bucharest is book two in the Moscow Wolves trilogy; at least, we assume it is going to be a trilogy. As regular readers of this blog know, pre-announced Russia-in-fiction trilogies are very much in vogue these days. See reviews of novels by Tom Bradby, Owen Matthews, and Ben Creed for further evidence.

Its title not-withstanding, The Starlings of Bucharest has many chapters set in Moscow. It is a terrific semi-sequel to the enjoyable The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt.

What do we mean by semi-sequel?

Set in 1975, The Starlings of Bucharest does not just take up where The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt —set between 1972 and 1974— left off. At least in terms of characters, it does not simply follow straight on. Only about halfway through do we come across Kit (or Christopher), the ambitious British diplomat whose celibate marriage of convenience to Martha formed the centrepiece of the first novel in the series. A little after that, British émigrée in Moscow, Eva Mann, reappears.

Only in the closing pages of The Starlings of Bucharest does the reader once again get to meet Martha, the central character and first person narrator of The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt.

At novel’s end, we are left with a hint that all is set up for Martha’s return to the fore in the trilogy’s finale —title as yet unannounced. Our roubles are on The Bears of Khreshchatyk, or maybe The Kingfishers of Minsk …

In The Starlings of Bucharest, the hero —if that is the right word for a naïve and uncertain young dupe— is a budding journalist by the name of Reginald Edward ‘Ted’ Walker. Ted is a young man from Essex determined not to follow in his father’s footsteps as a fisherman, out of Harwich. So he leaves home, taking with him his mother’s cash savings, and gets a job for an opaquely financed and little-known film magazine in London. The magazine specialises in the films of the Soviet Bloc. Ted specialises in imposter syndrome. He has no real qualifications for the job and a gauche innocence about life, politics, and relationships.

And yet Ted is sent to Bucharest and Moscow, at the height of the Cold War. Where he behaves as he will, oblivious —even hostile— to the warnings of various upper-class Englishmen, working for the government and keen to protect, if not Ted, then at least what they see as the interests of Britain, from the sly, intrusive, and sometimes brutal manipulation of Communist security services, the Securitate and the KGB.

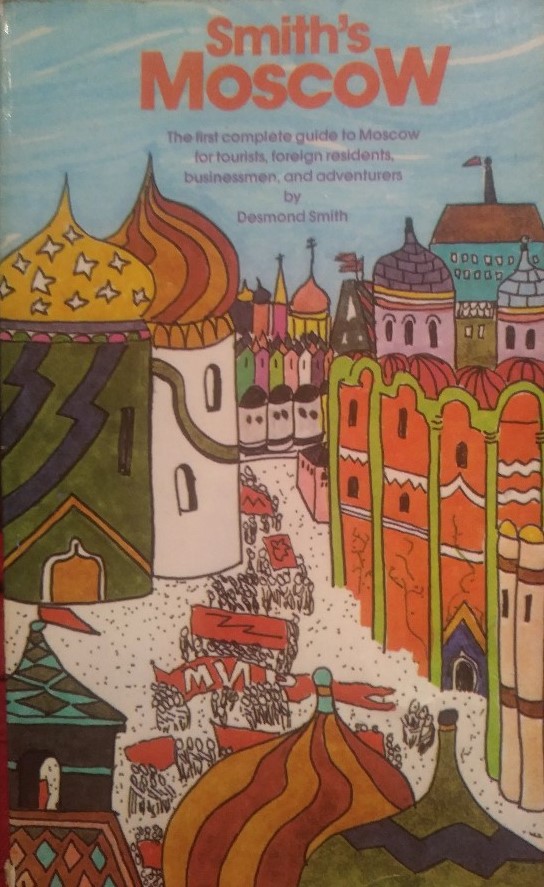

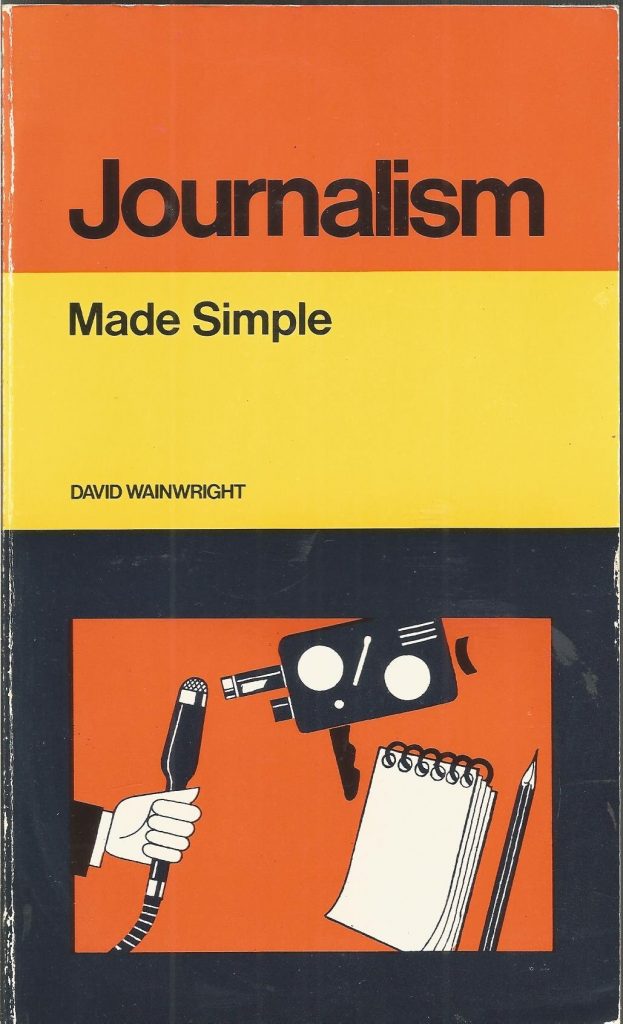

Using Ted as first person narrator, Sarah Armstrong skilfully prompts a fresh and guileless view of Cold War politics. How different is life in the Communist world from that experienced by the working man and woman in London, during the mid-70s era of decline and decay? Ted’s ‘expertise’ is second-hand. He has Smith’s Moscow guidebook in his suitcase along with David Wainwright’s ‘how-to’ book, Journalism Made Simple (1972). The simple suits Ted.

Wainwright’s book has a list of checks for journalists considering a society that is new to them. Ted tries to ask these first in relation to Bucharest, and later, when he returns home to England

Using the same questions that Wainwright prompted me to apply to Bucharest, I now looked at London: are the shops empty, transport links broken, the utilities not functioning, are there too many police evident? Do people look tired and hungry? Yes.

The STarlings of Bucharest, Chapter 9

By the end of The Starlings of Bucharest, Ted’s experiences in Moscow —including a brief involuntary visit to the Lubyanka— have helped him wise up and think for himself a little.

Wainwright’s list of checks for a society kept popping into my head. Are the shops empty, transport links broken, the utilities not functioning, are there too many police evident? Do people look tired and hungry? To my lengthened list, I would now add, are people too scared to look you in the eye?

The STarlings of Bucharest, Chapter 35

As ever, Russia in Fiction likes to ask about the portrayal of Russia. Whilst we know the truism that ‘Moscow is not Russia’, for many western visitors —particularly in the 1970s— it more or less was.

And Russia in Fiction loves the fact that Ted’s Moscow experience, in geographical terms at least, takes place within a walking distance area in the centre of the city. Essentially the action is played out in an area that goes no further north of the Kremlin than the few hundred yards to the now-demolished Inturist Hotel. Ted is booked in there but immediately moved just down the road, to the National, with its views up to Red Square and out across the Aleksandrovsky Gardens at the foot of the Kremlin wall.

Right: The National, with the Inturist towering behind

*************

The film festival that Ted is sent to takes place the other side of Red Square in the Rossiya Hotel, which this blog has overfondly described perhaps too often (see, for example, reviews of Joseph Hone’s The Sixth Directorate and Nelson DeMille’s The Charm School). Russia in Fiction misses the Rossiya Hotel, demolished a few years after the Inturist was brought to the ground; all part of contemporary Moscow’s desire (or at least that of its former mayor, Yurii Luzhkov) to rid itself of Soviet concrete-block architecture.

The Inturist tower has gone to be replaced by the shorter, stockier, and a thousand times grander Ritz Carlton. The National is now the Marriott. The Rossiya was so huge that its razing to the ground left room for the creation of Zaryadye Park.

Ted’s central Moscow sojourn is bounded then North to South by the Inturist and the Rossiya; and West to East by the Aleksandrovsky Gardens and —save for one brief visit to the KGB’s Lubyanka headquarters— the Hotel Metropol, where he is occasionally taken for a meal.

… oh yes, the novel. Please forgive the very Russia-in-fiction trait of focusing on the setting.

As with book one in the series, The Starlings of Bucharest makes as much of its temporal as of its geographical setting. Sarah Armstrong brings the 1970s to life and, for those of an age, to vivid remembrance.

The novel’s naïve first person narrative is interspersed by expertly phrased reports, written by the Securitate and the KGB, following their detailed observation of Ted. His every move is (mis)interpreted in the light of their attempts to ensnare and use him.

Despite Ted’s innocence, and a deceptive ease of narration, Armstrong sustains a sense of genuine, even mortal, danger under the surface. These are not simply silly games that grown men play in service of their regimes, East and West, but they have serious consequences. We learn, almost in passing, that Ted’s predecessor at the film magazine had just disappeared on a similar trip East. He is presumed dead —though it is the sort of presumption that leaves room for resurfacing in the next novel in the series.

The Starlings of Bucharest is a wonderful read. That a novel published in 2021 draws the world of the mid-1970s so well, and takes us so convincingly to Moscow in that time of Cold War competition and suspicion, marks out Sarah Armstrong’s writing as a Russia-in-fiction triumph.