Sometimes —and may be more often than usual in the middle of a pandemic-inflicted lockdown— a bit of escapism is just the ticket.

Step forward, James Patterson ‘the most borrowed author in UK libraries for the past thirteen years in a row’, and author of, well, who knows? 120? 130 novels? Several a year, mostly with co-authors.

Private Moscow is the 15th in the Private series about an élite detective agency with branches around the world, founded and led by all-action American hero Jack Morgan. From cover through to final page, it gathers in the Russia-in-fiction thriller clichés in a fast-moving action movie-style plot. But there is more to Private Moscow than that.

I stayed up into the small hours to finish it …

Let’s start with the cover. Strictly speaking, reviewing a book cover is not really on. After all, James Patterson did not write the cover. A silhouette of a figure is the standard go-to cover in thriller and crime fiction; preferably gun in hand. And if it is set in Russia, then Red Square, with St Basils and the Kremlin in view; preferably in the snow.

It didn’t take Russia in Fiction long to pick out more than a dozen ‘silhouette, Red Square‘ covers. Private Moscow joins that decreasingly illustrious list. Surely this penchant for silhouettes must soon have run its already too lengthy course? Our hope is that in a few years time we will look back on such covers as markers of a conformist age, and be amazed at their ubiquity.

As things currently stand, that hope seems vain.

Not that the cover says much about the quality of the story. There are some shoddy silhouette-covered thrillers and some great ones. It is just that it is hard to get away from them.

Russia in Fiction’s review immediately preceding Private Moscow is of David Bezmozgis’s literary novella The Betrayers (2014)? Silhouette cover.

In the coming week we are looking forward to the publication of Paul Vidich’s The Mercenary (2021). Silhouette cover.

Today we just finished reading (and will one day soon review) the quite excellent City of Ghosts (2021) by Ben Creed. Silhouette cover. [Update – reviewed 28 March 2021]

Talking of City of Ghosts, let’s use it as a neat link back to the book that this post is supposed to be reviewing; emblazoned across the front of Ben Creed’s novel is a commendation from James Patterson. If you are looking for a one-line review to put on the front of a first novel, then getting one from so prolific and popular an author as Patterson is the way to go.

And talking of prolificacy, if much online information is correct, James Patterson is helped in publishing so many books by not writing all of the words in between their covers. Apparently his ideas and his name make a large share of the Patterson contribution as he teams up with different co-authors; in this case, the latest big name in UK thriller writing, Adam Hamdy, author of the bestselling Black 13 (2020).

Cover nailed, the Russia-in-fiction smorgasbord offers several old favourites to choose from, and Private Moscow piles three classic dishes onto its plate.

First, we have sleeper agents; a theme that has appeared so often in Russia-in-fiction thrillers that to select a few titles seems disengenous. But Russia in Fiction has reviewed at least two novels with such a plot device this month already (Tsar and The Jericho Files), and is sure to review a good few more in the coming months …

… for example, and just because they spring readily to mind for now, Stella Rimington’s The Moscow Sleepers (2018) and Karen Cleveland’s Need To Know (2018), the German translation of which has the lovely title Wahrheit gegen Wahrheit.

The second selection from the Russia-in-fiction smorgasbord that Private Moscow selects is a breakthrough in military technology (‘Bright Star’) that would destroy the balance of power between the US and Russia. Again, there are many examples of novels that use the same high-tech military advance idea, but picking from those already reviewed by Russia in Fiction we see it in such as Tom Clancy’s The Cardinal of the Kremlin, Owen Matthews’s Black Sun, or Bart Davis’s Blind Prophet. This plot feature is a Cold War standard; it is interesting to see it still on the menu.

And the third oft-used plot device on the Private Moscow menu is one that complements the first. If you are going to have sleeper agents, then they go well with the ‘spy school’ idea. The notion that somewhere deep in the Russian countryside. Russian children are brought up as if in the United States, before being sent West to serve the Motherland. Nelson DeMille’s The Charm School (1988) is the finest of such novels, but by no means the only one; see for example Jack Higgins Confessional (1985), and of course the world of TV (The Americans) and the movies (Salt).

Yes, for Russia-in-fiction thriller aficionados, Private Moscow has some strong mainstream elements.

The Kremlin knows it has a leak. It doesn’t know who or where. Here’s this program you say could shift the geopolitical balance. What if one of these Bright Star agents has worked their way into a position of real power? How far would the Kremlin go to protect them?

Private Moscow, pp. 328-329

With dialogue like that, it is not exactly Le Carré. But it is not supposed to be. All of this is smoothly and page-turningly well done.

Here at Russia in Fiction, we have, as is obvious from this blog, read a lot of thrillers. But never before a James Patterson thriller. How does the man write several books a year? Multiple co-authors is part of the answer, but so too is the style which takes concise to levels we have rarely seen before in reading hundreds of works of popular fiction.

Private Moscow deploys new chapters where others would put in a paragraph break.

There are probably chapters in it that are shorter than this review so far.

No pretence. This is a down-the-line entertaining action thriller.

But from a Russia-in-fiction point of view, there is more to it than just selecting some standard features of the Russia-thriller genre.

Private Moscow makes the effort to seek out detail and draw out nuance; both features to its credit in a genre where too many would just tick off central Moscow landmarks, borrowed generalisations, and an ‘evil Russia’ with no light and shade.

To torture our analogy beyond what it should bear— what is a smorgasbord selection if you only choose the obvious dishes?

Beyond the spy school and sleeper agents, Private Moscow selects some rarer delicacies to add flavour; notably, the continued existence of the Black Hundred far-right organisation in contemporary Moscow, and that key feature of Russia-based detective novels, the rivalry between the security services and the regular police.

In Private Moscow, the titular ‘Private Moscow’ office is staffed by two people —the boss of the Russian branch of the Private detective agency, the savvy young Dinara, and the man whom she has recruited as its only other employee, an ex-Moscow City cop several years her senior, Leonid.

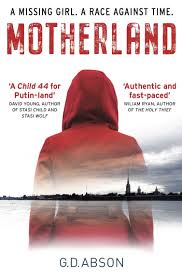

This is a pairing that put Russia in Fiction in mind of G.D. Abson’s detective novels set in St Petersburg — Motherland (2018) and Black Wolf (2019). The heroine of these, Natalya Ivanova, outranks her chauvinist male assistant, who is outwardly slovenly but in fact a congenial and at least semi-competent character.

The Black Hundred plot element, involving some unsavoury far-right figures operating out of a boxing club, goes beyond merely providing the muscle in the Russian underworld and creating the impression of a neo-fascist undertow to Russia’s politics.

Patterson and Hamdy make the effort to think through what these characters believe and what their ideological motivations are. A Private Moscow plot point turns on Dinara and Leonid observing a member of the group dealing drugs. Dinara explains the significance to Jack Morgan, Private’s overall boss.

“The Black Hundreds would punish him severely.” Dinara observed.

“Unless they’ve branched into new ways of making money”. Jack said.

Dinara shook her head. “Not these people. For them patriotism is bound up in the preconception of a wholesome life. God, country, family. Drugs would attack the very core of what they stand for.

private Moscow, p. 245

This pairing’s investigations provide the Russia-in-fiction detail that impresses within the fast-moving plot. Stand-outs include a vast communal unofficial safe-house for ex-police officers in the Kuzminki District, and —a favourite for personal reasons, because it was a regular route on my most recent Moscow visit— a chase scene under, up, and around the Krymskii Bridge near the entrance to Gorky Park.

Private Moscow surprised us here at Russia in Fiction. We thought —correctly— that a James Patterson novel would be a speedily read page-turner that builds its plot around some recognisable features in terms of what contemporary Russia looks like through the eyes of Western thriller writers. What we had not bargained for was an eye for detail, and plot features that go beyond the normal fare.