The Betrayers is set over a period of a couple of days, but unpacks several lifetimes of issues surrounding forgiveness, right decision-making, relationships, religious faith, the contingent nature of morality, success, and what it means to be a good person.

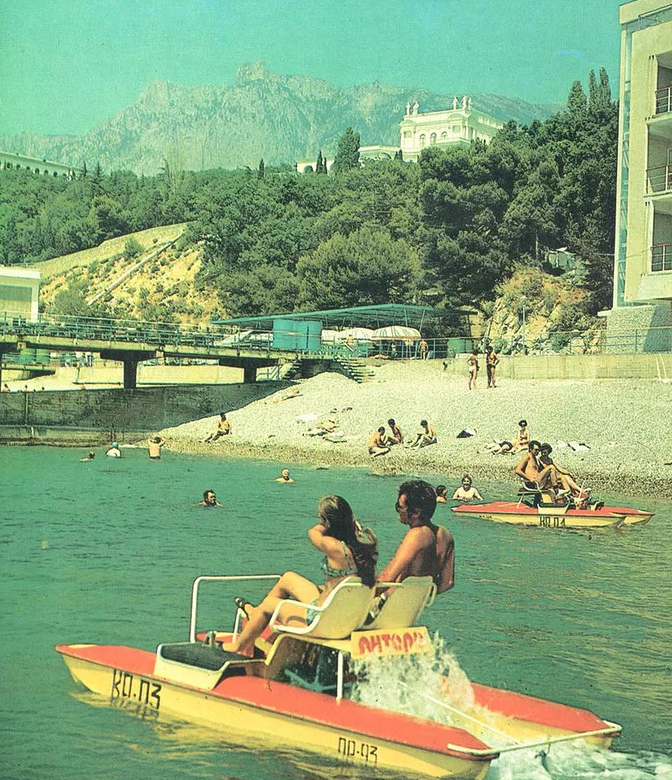

David Bezmozgis has excelled with this literary novel. Its physical setting is Crimea. As chance would have it, by the time of publication Russia had annexed Crimea from Ukraine, giving a certain unintended contemporaneity to The Betrayers. But the Crimea written of here is not tinged with any of its post-2014, post-reincorporation into Russia, resonance. Rather this Crimea, specifically Yalta and Simferopol, is portrayed as the run-down, faded and forgotten, former holiday haunt of the Soviet era.

The Crimea of The Betrayers is populated —at least so far as Bezmozgis’s story is concerned— with embittered characters, deadening the struggles of daily existence by living somewhere else in their heads, usually either the past or an imagined Jerusalem.

Central to the novel is the character of Baruch Kotler, a renowned Israeli politician, who had been born and brought up in the Soviet Union. As a young man, Kotler was a dissident; a sort of Natan Sharansky character, imprisoned by the Soviet authorities for agitating against the Communist regime. Now, decades on, a leading public figure in Israel, he flees to Crimea with his young mistress in an attempt to escape exposure as an adulterer at home.

Why does Kotler choose Crimea as his temporary bolt-hole? Partly because of its out-of-the-way location, and partly to relive a distant childhood holiday.

Whilst Kotler comes to Crimea to run away from current circumstance, he soon runs into the ghosts of his past. By the unlikeliest of chances, he comes across the former KGB stooge whose testimony had condemned him to 13 years in the Gulag labour camps during the Soviet era.

This simple set-up is complicated by layer on layer of revealed depth. The events which this leap into another life entail become entangled as the story progresses and the reader learns more of Kotler and his wife and his children and his mistress.

Such density of plot and character abound too in the portrayal of his Soviet-era betrayer, of whose life and circumstances Kotler knew little back in the Communist days, and whose current travails are portrayed for the reader before they are revealed to his one-time victim and now potential saviour.

It is writing of a high calibre; tightly constructed, and beautifully pitched.

For the Soviet/Russia angle, what stands out in The Betrayers is the portrayal of how Soviet life was lived, and, for many of a certain generation, the disappointment with what followed. This is not 1990s distress at poverty, chaos, and the collapse of everything. This is disenchantment with the settled post-Soviet world.

The contrast is implicit in the novel’s setting; as Crimea represents the carefree summer days of youth.

Ex-KGB man Tankilevich now struggles to get by in a shabby house on the outskirts of Yalta. He slumps in front of the TV and watches

… the insipid programming from Channel One in Moscow. A game show hosted by a facetious impresario. A benevolent vozhd who behaved towards the contestants —bumpkins and workers— as if they’d come to touch the hem of his Italian suit. This was what the struggle for freedom and democracy had delivered. Bread and circuses. Mostly circuses. From one grand deception to another was their lot. First the Soviet sham, then the capitalist. For the ordinary citizen, these were just two different varieties of poison. The current variety served in a nicer bottle.

…

The game show was offensive, but there were no words for the newscast. Every lie starched and ironed. The pomp of a new agreement between Russia and Western corporations to drill for oil in the North Pole. Which everyone knew meant billions of dollars to the same crooks. Condemnation of America for interfering in the affairs of sovereign states. Which meant defending the rights of Arab dictators to shoot their citizens with Russian guns. A clash between authorities and violent demonstrators in Moscow. Which meant the criminal regime stifling dissent … Moscow, Kiev, or Minsk. The same methods prevailed.

the betrayers, pp. 97-98

Bezmozgis’s wonderfully pithy and quotable phrases stand out.

‘She’s a grown girl. A young woman. No longer a child, as she is quick to remind me. A father doesn’t fully realize this until it stares him in the face. It isn’t all bad. Sooner or later, the realization arrives: the child discovers the immaturity of the parent, and the parent the maturity of the child’ (p. 51).

‘ … he was exposed to people in positions of power and saw how many of them were inadequate, even mentally and morally deficient. Little more than noise and plumage.’ (p. 138).

‘The rival flows of mysticism and science that irrigated the Russian heart, a manifestation of the failed Soviet project. Backwardness yoked to forwardness.’ (p. 179).

the betrayers

Of particular relevance to the story’s development is the novel’s aphoristic description of those who chose the path of dissidence in the Soviet era.

Dissidents were by nature contrary. They would find fault with Paradise and send God a petition.

the betrayers, p. 148

The Betrayers is replete with thoughtful and thought-provoking vignettes. Russia in Fiction was particularly taken by Kotler’s musings on whether he could go back to being a ‘normal’ person after the heights of political fame which he had achieved.

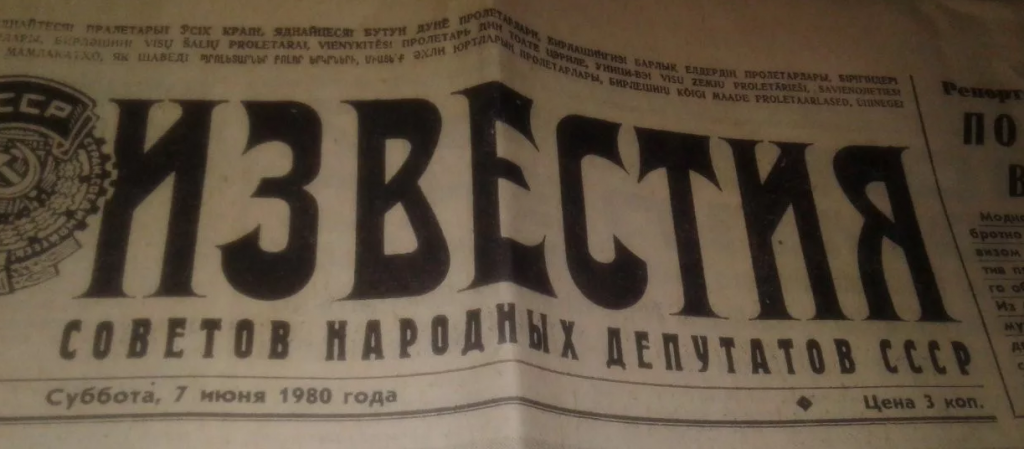

Who was the man who thought these thoughts? It came as something of a surprise. Not because of the thoughts —he didn’t dispute the thoughts— but their pitch. The pitch of a public man who expected his thoughts to have injunctive force in the world. In spite of his true nature, he’d become this man. Forty years earlier, he’d been thrust, unwittingly, into this role by Tankilevich. Neither of them could have anticipated where it would lead. When he’d first seen the article in Izvestia, his head swam.

Then, two weeks later, on the street outside his apartment, half a dozen agents swooped, surrounding him, their many hands clutching his coat and tossing him, limp as a rag, into the waiting car.

From such pathetic beginnings he rose … And once he rose, it was hard to return to the man he’d been before —a fairly ordinary man, with no grand designs. A former musical prodigy with small hands, a degree in computer engineering, and a desire to live in Israel. This described nearly every Zionist in Moscow.

… So why couldn’t he now return to his orginal humble ambitions: to lead the life of an ordinary citizen in his ancestral homeland? How many other immigrants were there, even former refuseniks, who’d attained just that sort of life?

… Only an egomaniac thought in terms of anything more exalted —to be a leader of the people, a second Moses or Ben Gurion.

the betrayers, pp. 137-138

The Betrayers deserves to be better known than it is. A real treasure of a tale; its plurality of title hints at the nuanced probing of human nature within. Its present-past temporal setting, alongside Crimean location, combine to create a Russia-in-fiction gem.

And to celebrate such works is one of the reasons Russia in Fiction is here.