Can we get the excuses out of the way first? Russia in Fiction reviews all sorts of stuff. Basically, if it is fiction that is set in, or at least features, Russia, then we might review it. Reviewing a book is not recommending a book. The idea is to get a sense of how Russia is portrayed in the popular imagination.

But even so, Russia in Fiction did a lot of umming and aahing before reviewing Ted Bell’s Tsar.

You know those heavy metal bands that are so over the top that you wonder whether they are being deliberately ironic, taking the mickey out of the genre itself? Think the movie This Is Spinal Tap (1984) and the amplifiers that go up to eleven because full-volume ten is not loud enough. That’s what Ted Bell’s Tsar reminds me of. It has all the usual elements of a Russia-related thriller, but ramps them up to beyond believable.

Of course, international political thrillers thrive on some level of exaggeration. If you write a thriller about a sleeper agent, then they are about to take over the presidency or become Prime Minister. If you write a thriller about a secret weapon, then it is on the verge of being launched, or activated, or whatever. Russia in Fiction’s basic rule (or let’s call it a preference so we don’t sound too proscriptive) is that the plot has to be capable of being believed even if at some exaggerated level.

In Tsar we have the not uncommon idea of a post-Putin president being a hardline anti-westerner, re-opening the labour camps and killing those who oppose him. Except in Tsar the opponents are killed by being impaled.

In Ted Bell’s novel Russia’s latest leader takes on the eponymous title of Tsar, having imprisoned Vladimir Putin. Except in Tsar, Putin is not just in prison, he is in a dungeon over a nuclear waste dump where he has to wear lead-lined boots to keep himself alive.

As in many thrillers, the actions of Russia’s rulers present a threat to global peace. Except in Tsar that threat consists of mini-bombs concealed in personal computers sold in their millions across the world, designed by Russia’s leader who also happens to be a Nobel Prize Winner, composer, and general all-round genius.

You get the picture.

Take a glance at the online customer reviews of Tsar and it is a portrait of polarisation. Loads of people writing along the lines of ‘this is great, really exciting stuff, showed me how dangerous Russia is today , 5 stars’. Loads of people going down the ‘this is ludicrously unrealistic, 1 star’ route.

And loads of people —from 5 to 1 star— pointing out the borrowing from Bond. James Bond. Or at least the cinematic version, rather than Ian Fleming’s highly readable novels

The hero of this book is an English ex-military figure, seemingly modelled in many respects on James Bond, but without much subtlety.

There is an almost exact description of the famous Ursula Andress scene in Dr. No, coming out of the sea onto a Caribbean beach wearing a bikini and collecting shells. Except in Tsar the bikini has no top.

Or there is the meeting of Russia’s governing cabinet that sees the country’s leader having two of those present shot at the table, in true Bond villain, SPECTRE ruling council style .

No, subtlety is not a strength of this book. The violence is more violent than usual —one graphic rape scene being particularly notable in this respect. The plot lines leave credibility behind very early on. OK, if that is what you want.

*******

Russia in Fiction does a neat sideline in Putin in Fiction. In most Russia-related novels that deploy the character of Putin, he is simply a personalisation of a big bad resurgent Russia trope.

Except in Russian language thrillers of course —for example, Президент (Prezident), 2002.

Two of the more interesting portrayals of Putin in English language fiction come from early and late in his imagined life. Henry Porter’s Brandenberg (2005) depicts the Vladimir Putin of the 1980s, when he served as a KGB officer in Dresden. Michael Honig writes of The Senility of Vladimir P. (2016) a decade or so in the future.

Given how most of the time, Tsar is a novel turned up to eleven, it was a relief to have within it a slightly nuanced Putin character. Though how nuanced a character can be who is depicted as living in a cell with lead boots and a lead-lined mattress to protect him from radiation in a prison that has a room full of the regime’s opponents impaled alive on wooden stakes is a moot point. Within this over-the-top setting, Putin is made into a sympathetic character; the overthrown president who was truly a democrat whilst trying to bring Russia the stability he believed it needed above all (p. 493).

In Tsar, the Putin figure and his successor, Vladimir Rostov, are an amalgamation of the real Putin. Rostov shares much from the real Putin’s autobiography, including first name, patronymic, and place of birth. Ted Bell —using the time-honoured thriller/crime writer’s technique of deploying a briefing as a means of giving key information in didactic style— has the character of ‘C’ (Head of British Intelligence) deliver a mini-biography of Rostov that could have been taken from many a pen-picture of Putin in the 2000s, but with a few details changed.

Vladimir Vladimirovich Rostov, known popularly as Volodya, was born into a poor working-class family in 1935. Both parents were survivors of Hitler’s brutal nine-hundred-day siege of Leningrad. His two brothers were killed by the Nazis and his father grievously wounded in the defense of the city …

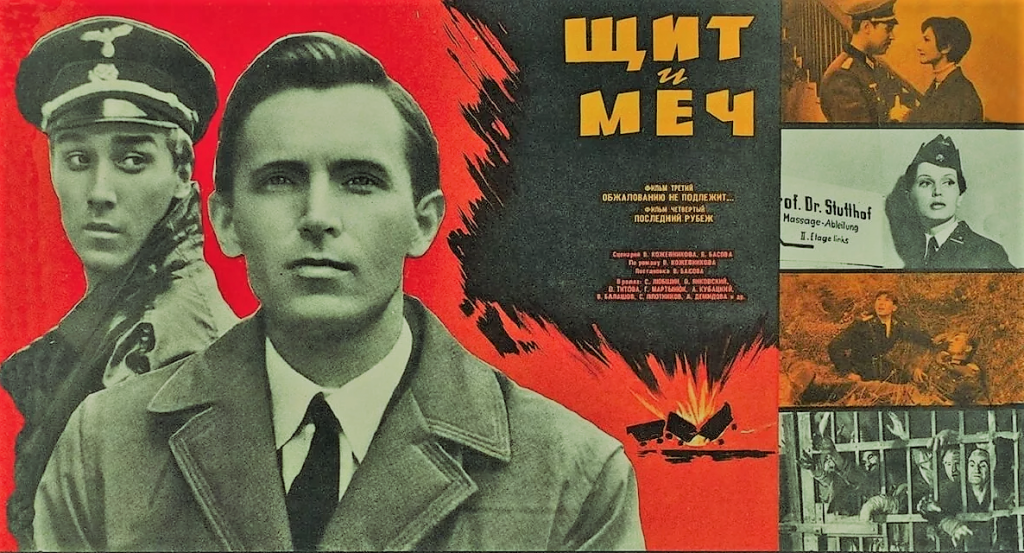

At age fifteen, Rostov saw a film, The Sword and the Shield, which glorified a Soviet spy’s exploits in Germany during the war. He tried to join the KGB at age sixteen. Just marched into the local headquarters and asked to sign up. They turned him down, obviously, and told him to get a university degree, study law and languages. He did, and they recruited him upon graduation from Leningrad State University …

Tall, thin, and delicate in appearance, our little Volodya, at age ten, fell prey to neighbourhood bullies. He began a lifelong study of sambo and judo …

Rostov’s inherent inscrutability and judo were perfectly matched. He’s got an innate ability to read his opponent’s moves whilst concealing his own intentions . It’s not a sport to him, it’s a philosophy.

Tsar, pp. 97-98

Most of that is straight from the real-life Putin biography. Except the date of birth (Putin was born in 1952) which then makes it impossible for Bell’s President Rostov, born in 1935, to have watched The Sword and the Shield (1968) at the age of fifteen.

Pedantry. A Russia in Fiction trademark. Though we do try to rein it in a little.

And let us be up front about it, although Ted Bell has put lots of Russia-related facts in Tsar, he gets enough wrong. Sometimes it is glaringly wrong in a not-understanding-Russia sort of way. A stand-out in this regard is the scene in which Russian mafia figures based in Miami throw a party for a known Chechen fighter responsible for terrorist acts in Moscow. He would more likely be a hate figure to them than an honoured guest.

Othertimes Tsar is more off-key wrong. Whilst many a Russia-in-fiction novel makes play of the rivalry between the GRU (military intelligence) and the KGB/FSB (state security) —for example, Bart Davis’s enjoyable 1986 novel Takeover— Ted Bell has them as the same organisation.

Russia’s president enters the ‘brand new GRU complex’ in Moscow.

The frequency with which each new regime changed the names and acronyms of various institutions was a holdover from the old Chekist days: secrets within secrets.

Every breathing soul in Moscow knew this building for exactly what it was: KGB headquarters.

Tsar, p. 26

This review has done Russia-in-fiction pedantry. Let’s finish off with a bit of Russia-in-fiction pretentiousness.

In Bell’s novel, the Tsar figure’s genius as an inventor and computer expert includes him inventing a computer for which the ‘screen’ is a holographic image that appears in the air. This is as envisaged in the near future by Vladimir Sorokin in his short novel День опричника (Den’ oprichnika, 2006).

Wow, comparing Ted Bell to Vladimir Sorokin, a writer of actual Russian literature. That is not a comparison that tells you much about Tsar.

Tsar is an action thriller, full of set-pieces recognisable from the genre. The hero who alone can save the day. More caricatures than characters. There are some brutal and explicit scenes. It is what it is.

Ted Bell has written plenty of subsequent novels and clearly pleases his audience. From the publisher’s information, later stories appear to include President Putin, presumably released from his lead-booted existence in a radioactive cell and back in the Kremlin. Even with 60+ more reviews to go before Russian in Fiction reaches its century goal, we don’t anticipate returning to Ted Bell.