Ssshh, I’m sneaking this book into these ‘Russia in fiction’ reviews , despite the fact that Henry Porter’s Brandenburg is not about Russia or set in Russia.

So why am I mentioning it here? Two real reasons: first, it’s just a terrific book — one of my favourite political thrillers; second, whilst it might not really be ‘Russia in fiction’, it does feature —as a major character— a young Vladimir Putin, serving as a KGB Colonel in Dresden.

Brandenburg is not quite Russia-in-fiction; it is about East Germany, and specifically is set in the couple of months up to —and including— the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. It portrays vividly the end of the Communist regime in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic, GDR). So at least it is about Communism, if not the Soviet Union per se.

Technically, revealing the fact that a young Putin is a central character represents something of a spoiler, as the full name of the character ‘Vladimir’ is not revealed until the 450-page novel’s climax. But for the alert reader who knows Putin’s biography, the reveal is a lot earlier.

The novel’s hero, East German dissident Rudi Rosenharte, gets KGB man Vladimir’s help, working against the GDR’s Security Services, the Stasi.

‘I’d like to know the name of the man I have entrusted my life to. You have enough knowledge to have me executed.’

‘As I said just now …’ A smile twitched at the corners of his mouth.

‘I do not like to be exposed. However, since you ask, it is V.I. Ussayamov —Major Vladimir Ilyich Ussayamov.’

…

Rosenharte’s eyes had strayed to a box upholstered in blue satin, where a silver medal was displayed. He knew enough of the Cyrillic alphabet to see that it was a first prize awarded in a judo tournament to a man with the initials V.V.P.

Ussayamov was his cover name.

brandenburg, p. 208

So, my excuse for reviewing Brandenberg is that it is part of the ‘Putin in fiction’ genre, rather than the broader ‘Russia in fiction’ category.

In most Western thrillers where Putin appears —either identified by name or in a lightly disguised version— he tends to be a little one-dimensional, and certainly, to be simplistic, a baddie rather than a goodie. (With the possible exception of Ted Bell’s Tsar; but in that rather over-the-top thriller, Putin is only a sympathetic figure in contrast to his completely bonkers authoritarian successor).

Of course, in Russian thrillers, the opposite is the case. I have on my shelf such a Russian work, by Alexandr Ol’bik, called Prezident (2002), with a cover that looks like this.

The back cover blurb of Prezident can be roughly translated as follows:

Is the president on holiday? That’s what the media say. That’s the official version but where actually is the president now?

There, where the endless war in the Caucasus is burning.

There, where the president must take on terrorist fighters.

There, where victory demands all his experience, all his courage, and all his ability to take risks …

Russia is lucky —finally we have not simply a president— but a real man! A guy able to do all the work that a man has to do …

In Brandenberg, Henry Porter’s Putin is better drawn than in both of these typical cases. He is a very smart operator who sees the way that the wind is blowing, in terms of Communism’s decline, and is good-natured in his personal relationships. He is happy to work alongside the dissidents protesting against the old school authoritarianism of East Germany’s Communist leadership, as well as in a mutually advantageous collaborative relationship with British and American intelligence.

I don’t doubt that many readers today will wonder what lies behind what must seem such an oversympathetic portrait of Vladimir Putin. But, given that this novel was presumably written during Putin’s first term as President of Russia (2000-2004), when Russia’s foreign policy could accurately be summed up as strengthening Russia alongside, rather than against, the Western world, then Porter’s portrayal makes more sense.

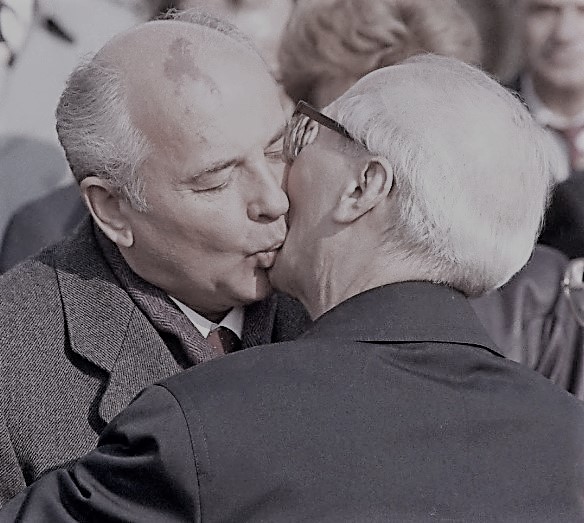

Making judgements on the fictional Putin in Brandenberg, is in any case an exercise carried out at several removes. As just noted, the Putin of the third decade of the 21st century is a different figure from the first-term President Putin, known to the world when this novel was published. But of course, the novel is set even earlier still, in the autumn of 1989. The reforms of the Gorbachev era in the Soviet Union had been resisted by East Germany’s old-style, hardline Communist leadership, headed by Erich Honecker.

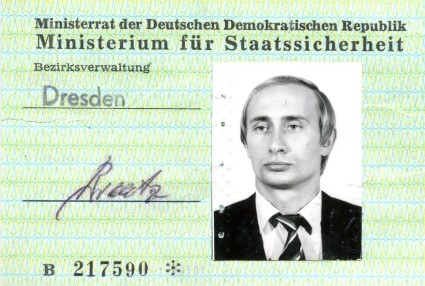

Putin spent most of the Gorbachev years as a KGB Colonel stationed in Dresden with his wife and two young daughters. Whilst increasingly dramatic political, social and cultural changes brought the loosening of restrictions back home, Putin watched from abroad, stuck in one of the the Soviet bloc’s most conservative countries. Whilst the USSR pulsed with change under a vigorous young leader, the elderly Erich Honecker presided over a sclerotic system wedded to old-style Soviet socialism.

As Communism collapsed, Putin returned to Leningrad (shortly to once again be named St Petersburg), resigned from the Communist Party, and hooked up with the democratic reformer Anatolii Sobchak. The disdain that Porter’s Putin has for the brutally myopic Stasi fits this biography well.

Beyond the politics, Porter imagines a young Putin with a core of inner strength and a wicked sense of humour. In a scene towards the end of the novel, Rosenharte is negotiating for Vladimir’s help to spring two prisoners —his lover, Ulrike, and ‘Stasi officer turned good’, Biermeier— from a high security Stasi jail in Berlin.

[Vladimir] smiled and offered Rosenharte a chunky silver cigarette case engraved with the initials VVP.

‘I’m not going to lose anyone else to that place,’ said Rosenharte quietly. ‘… I can’t let that happen. One way or another I’m going in to get her, so it’s in your interest that I do this with the minimum of risk. It’s very important to you that I don’t get caught, isn’t it, Volodya?’ He intentionally deployed the nickname he’d heard the other Russians used when he entered Number Four Angelikastrasse [the KGB’s Dresden headquarters] that afternoon in the boot of a car.

Vladimir shook his head and sat down. ‘That’s a form of blackmail. I won’t accept it, Rudi’. He paused and handled the cigarette case, evidently getting some satisfaction from it. ‘In our game we always need a return on risk.’

…

Two possibilities occurred to Rosenharte. Either Vladimir was acting outside his authority or he was a more important player than he had let on. Perhaps the Dresden HQ was a kind of cover, concealing a more top-flight KGB operation than the down-at-heel offices would suggest. Perhaps Vladimir had no boss and was running things himself.

‘Okay. You provide the passes for myself and one other man and the release documentation in Ulrike’s name … What about Biermeier?’

‘Don’t tell me you’re in love with Biermeier too?’

brandenburg, pp. 364-365

If you are interested in Putin’s Dresden years, there are a couple of good articles, both replete with engaging photographs. One from the BBC, and one from Russia Beyond.

If you are interested in Putin in fiction, Henry Porter’s Brandenberg is a must read. And the same could be said if you like fast-moving, well-plotted, political/espionage thrillers, written by a superior author who puts in the effort necessary to get the details right.

Alongside the page-turning entertainment, I learnt —or was reminded of— a good deal of detail about the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and the failing, brutalised society of the GDR, dominated by the ubiquitous Stasi, whose informers some estimates put at one in six or seven East German adults.

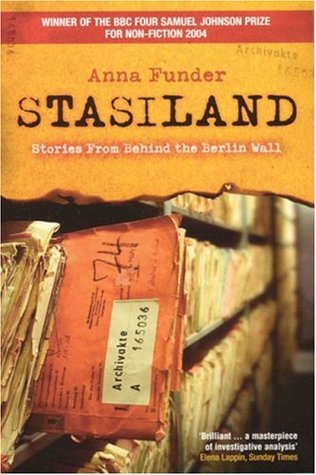

If, like me, you’re a Russophile whose interest in East Germany stems primarily from it being a part of the Soviet bloc, and you want to read more about the Communist secret police in those years, I recommend Anna Funder’s Stasiland (2003) – an engaging read about a brutal subject.