Part two of this review is here.

Are you familiar with the notion of nostalgia for a time or place that you have never known? Anemoia is the term.

Or perhaps, as we are dealing here with a novel translated from German into English, the German word Sehnsucht is appropriate; often simply translated as nostalgia, it has a sense of wistful vagueness that the more common German word Nostalgie does not have.

Michael Wallner’s novel prompted anemoia in me.

And while we are playing around with anemoia, Sehnsucht, and Nostalgie, let’s not forget the German neologism Ostalgie, a portmanteau from Ost —meaning East— and Nostalgie. Ostalgie refers to nostalgia for aspects of life under Communism.

Specifically, in the German case, Ostalgie looks back to life in the German Democratic Republic, and in particular, cultural aspects of that life.

What has any of this got to do with The Russian Affair? One of the reasons why I love this book —and indeed a number of other books set in the Brezhnev years— is that it stirs in me a vague nostalgia for elements of that time and of that place.

There are a couple of caveats to note. First, don’t get me wrong, as one of the authors of the book Brezhnev Reconsidered (Macmillan, 2002), I am neither oblivious to nor supportive of the political and moral faults of that particular version of Soviet authoritarianism.

Second, my feeling is not pure anemoia. Whilst I did not live in Russia in the 1970s, that most of my childhood played out in that decade gives me a certain nostalgia for those years which is then coupled with the fact that I did, albeit briefly, live in the Soviet Union just a few years after the Brezhnev era ended. So, acknowledging an element of false memory, 1970s USSR does not seem completely alien to me.

Well, several paragraphs into the review and I have scarcely mentioned the content of The Russian Affair. Unlike the majority of books reviewed here, Wallner’s book is not a thriller in terms of genre, but a more literary novel about the competing pressures, primarily economic and emotional, facing Muscovites during the high Soviet period of the Brezhnev years. Wallner weaves a moving story from the familiar threads of that time.

The novel’s heroine —Anna, a municipal painter and decorator— lives in a small apartment which three generations are forced to share. Anna, Anna’s husband, and their young son all live cramped up with Anna’s ageing father.

The novel’s set-up, as described in the preceding paragraph, is alone enough to open a door into two of the most dominant domestic themes of Brezhnev-era Soviet life —housing and the role of women. If you want to explore them in a more contemporaneous and lived sense than offered by the novels reviewed in this Russia in Fiction blog, then seek out some of the Soviet literature of those days. These themes were very present.

Two of the finest Russian authors of the Brezhnev years —Vladimir Voinovich and Yurii Trifonov— wrote short and beautifully crafted stories about trying to get a better apartment in Moscow.

Voinovich was deemed politically unacceptable in the Brezhnev years. He could no longer get published in the Soviet Union, was harrassed by the regime through much of the 1970s, and was eventually forced into exile in Germany. There is a lovely, detailed and personal account of his life in this 2018 obituary by Cathy Young. Like her, I was fortunate enough to meet Vladimir Voinovich; and I too remember him as a larger than life figure.

Voinovich’s story The Ivankiad (1976) is best summed up by its sub-title: the tale of the writer Voinovich’s installation in his new apartment. It gives a vivid account of Voinovich’s dispute with a member of the Soviet literary élite over the right to an apartment in the gift of the Soviet Writers Union. Voinovich was thrown out of the Soviet Writers’ Union. Then he was thrown out of his country.

Voinovich’s contemporary, Yurii Trifonov, in some ways had much in common with him. And not only the fact that both were married three times. Trifonov too wrote both historical novels and also more contemporary stories that portrayed the difficulties of everyday life in Brezhnev’s Soviet Union.

But Trifonov never became a dissident; he was perhaps more careful in that respect than Voinovich. Their writing styles illustrate the difference — where Voinovich was in-your-face, sometimes hilarious, sometimes furious; Trifonov was a little more nuanced, pointing the reader in the direction of desired conclusions.

Trifonov’s The Exchange (1969) takes on the theme of generations living together that features in The Russian Affair (in case you forget that Wallner’s novel is what I’m supposed to be reviewing here). In The Exchange a young couple try to complete an apartment exchange before the imminent death of an elderly parent, as this represented one of the few ways to gain them more living space.

As I am clearly not going to get much further with The Russian Affair review for now (that will have to wait until part two), let me finish part one by returning to how a subject central to Wallner’s novel was also tackled by Soviet writers in the Brezhnev year.

Wallner’s heroine Anna is portrayed as frequently frazzled and exhausted by holding down a job, keeping house, bringing up a child, queuing for scarce goods, and all in a time of shortages where knowing the right person, having the right connections, could be key to making day-to-day life a little easier.

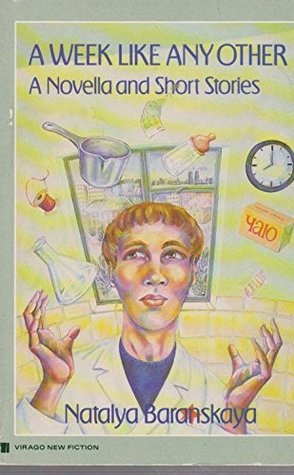

Natalya Baranskaya’s best known story, A Week Like Any Other (1969), portrays the ‘double-burden’ carried by Soviet women that became increasingly discussed in the 1970s. The emancipation into the workplace (the heroine of A Week Like Any Other is a scientific researcher in her mid-twenties) did not feel so emancipatory when coupled with continued domestic expectations in terms of keeping house and bringing up children.

If you don’t read Russian, happily all three of the stories noted above (The Ivankiad, The Exchange, and A Week Like Any Other) have been translated into English. Well worth a read in each case.

But, as noted from the start, the Russia in Fiction blog is not really about Russian literature. Strictly speaking, it is about Russia portrayed in English language fiction. This review of Michael Wallner’s The Russian Affair is already cheating on the blog’s premise, since the book is a translation from the original and so is really German language fiction.

And then to cap it all, part one of the review has scarcely mentioned Wallner’s terrific novel. For that, you have to read part two.

Part two of this review is here.