Part one of this review is here.

The Russian Affair alights on themes of Moscow life in the high Soviet years of the Brezhnev era.

Just as Soviet authors of the late 1960s and early 1970s did, Michael Wallner frames his story around everyday problems —multi-generational living in cramped apartments, the ‘double burden’ carried by Soviet women, access to essentials in a time of shortages, the importance of social connections, the ubiquity of the vlasti (the authorities), and the treasured pleasures and freedoms of normality around the ‘kitchen table’ inner circle of family and friends.

In early 1970s Moscow, twenty-seven year old Anna Tsazukhina, her husband Leonid, their young son Petya, and Anna’s father Viktor all live together in one apartment.

Viktor is a rather faded poet of earlier renown, in a time and place where poets were in some senses the Soviet equivalent of rock stars. Leonid is a Red Army officer, whose absence from the home due to lengthy postings in distant parts of the Soviet Union leaves Anna to fend for the somewhat sickly Petya, at the same time as holding down a manual job as a municipal painter and decorator.

Struggling with the double burden of job and housekeeping is made more difficult by the shortages of those years. But life is easier for the Communist élite, with their ready access to goods and services not available to the ordinary worker in this workers’ state. Anna’s particular predicament is made worse when her son requires the sort of medical treatment not provided to the ordinary Soviet citizen.

Against this background, the story unfolds of the relationship between the good-looking young Anna and an older, senior Party member.

He is a sympathetic character, and this is no tale of blunt blackmail. But disentangling personal feelings from the access to quality medical care for her son that the relationship brings about provides the novel’s emotional pull.

There is one final common and constant element of life in the Brezhnev years to be included in the mix, namely, the near ubiquitous presence of the KGB. When it is gently but firmly suggested to Anna that she might inform on her Party acquaintance, the decisions facing her become more complex still.

With regard to its Russia-in-fiction elements, The Russian Affair convinces with its knowledge of the Soviet Union, and Moscow in particular, in the 1970s. The physical setting is conjured up well, from large-scale to telling detail.

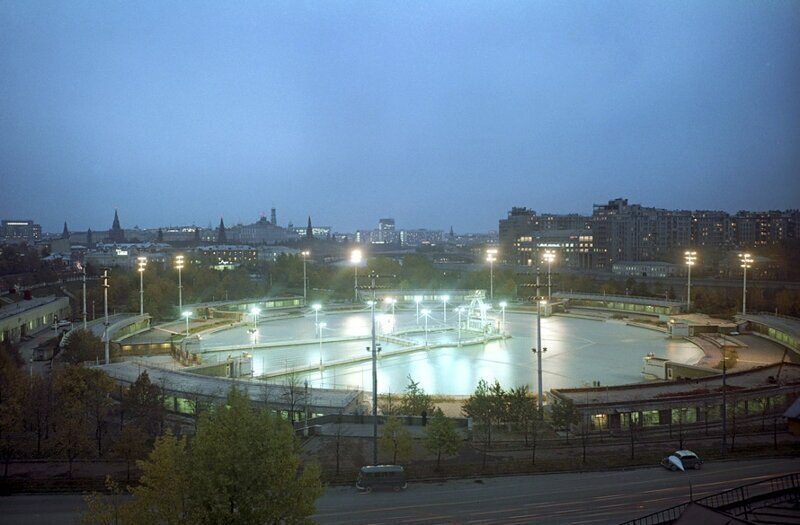

Reference to the outdoor swimming pool incongruously constructed ‘on the very spot where the Palace of Soviets was supposed to be built’ may well be a common motif in novels set in the Moscow of this time, but it delighted me nonetheless.

Sadly I never swam there, but I remember driving past in a coach one night, amazed at this city centre landmark, steam rising floodlit into the winter sky. I think of that sight whenever I visit the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, built on this spot in the 1990s.

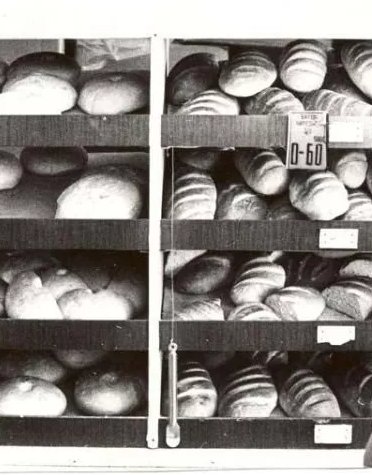

And with regard to the telling detail, there is an important scene in The Russian Affair that takes place in the seemingly mundane setting of a bread shop. I was taken back even to the smell and feel of buying bread in the Soviet Union simply by mention of one small feature of this process that I had long forgotten

‘she took the long-handled spoon from the counter and pressed the metal into the loaves that were on offer’.

Michael Wallner’s writing is replete with such details; the sort of authentic and evocative description that the Russia in Fiction blog loves. I don’t know enough of the author’s biography to be able to judge whether these insights stem from personal experience or from diligent research, but he was born in 1958 and so the 1970s would at least have been formative for him.

Wallner is Austrian, with a background in the theatre. The brief summaries of his life that I have found online cover no more than a few lines, listing work in Austria and Germany with no mention of any time in Moscow. But surely he, or someone close to him, was there? The Russian Affair certainly reads as if its author knows the time and the place well; but I guess that is what accomplished writers of fiction can achieve.

Part one of this review is here.