Stephen Coonts is at the forefront of the book-a-year thriller writer stable, and has been since the 1980s. Like many others (Tom Clancy, Stella Rimington, Daniel Silva, to name but three of a long list), he often writes about the same characters — in the case of Coonts, the chief protagonists in his fiction are Admiral Jake Grafton and CIA officer Tommy Carmellini.

Coonts less often writes about Russia, but even that, he does with relative frequency —for example, The Red Horseman (1993), Fortunes of War (1998), and Wages of Sin (2004).

What Coonts does, he does well; namely, snappy and well-plotted action thrillers. He is an ex-military man and, from what I have read —basically, the Russia-related titles named above— his politics seem to be patriotic American.

Coonts is not alone amongst thriller writers in embracing the return of Russia as the United States’ ‘main enemy’ in the second decade of the 21st century; a position which gained ground after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and became firmly established with the rise of Donald Trump to the presidency and its accompanying allegations of Russian connections. It is in this latter milieu that The Russia Account is set.

The basic premise of the plot is that Russian banks, probably with the backing of the Russian state and Vladimir Putin personally, are seeking to undermine the US economy by flooding it with fake dollars. Anyway, the strength of the novel as a zip-along thriller lies primarily with its well-written action scenes.

The Russia Account makes little attempt to disguise the real life allusions that its author is making. It has a failed presidential candidate called Cynthia Hinton, the wife of former president Willie Hinton, who

went to the Russians for a fake dossier on you [the successful Republican presidential candidate] that she could use to keep you from being elected. When that didn’t work, the deep state had you investigated by special prosecutor.

the russia account

Russia-related content is straightforward, to say the least. There is a former KGB man who, on the collapse of communism, used his position to buy state-owned assets

suddenly the whole damned country was for sale. Factories, military equipment, aeroplanes, airlines, banks, everything. You signed promissory notes and you were the new owner, a capitalist.

the russia account

Much is made of Russia being comparatively weak in comparison with the United States. There is one paragraph that reads like a summary in a textbook of global economies

although it [Russia] contained 144 million people, its economy would rank fourth if it were a state in the US, behind California, Texas, and New York.

the russia account

One thing that jarred with me in an otherwise enjoyable romp through this fairly light page-turner of a thriller, was the apparent lack of research into Russian names. It stood out —the Russia in Fiction blog has a bit of a thing for the names that authors choose for their Russian characters.

Surely a writer of the standing of Stephen Coonts would take the time to get a sense of what names are Russian and what names are not? There is an oligarch in The Russia Account, ‘one of Vladimir Putin’s cronies’, called Yegan Korjev. What sort of name is that? Not a Russian one.

And another Russian character —actually making a reappearance, having featured in Fortunes of War (1998)— called Janos Ilin.

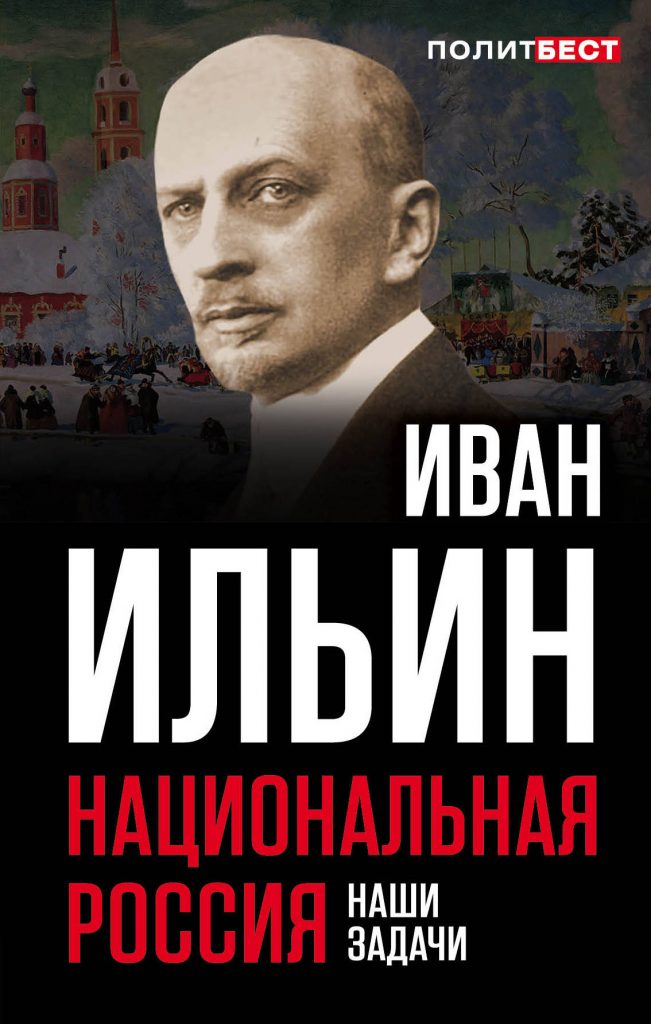

OK, so Ilin —or at least Il’in— is a Russian name, as anyone who follows Putin’s dabblings with philosophy would recognise.

But Janos? As Hungarian as you can get, although the character isn’t. It is all very strange.