Part two of this review is here.

Great wealth, hedonistic parties, thwarted love. A young man who lives next door to an extraordinarily wealthy figure into whose world he is drawn.

That same extraordinarily wealthy figure is seeking to win back a girl whom he had loved and lost, who lives across the way from him, but is now married to someone else.

Nick, Tom, Daisy, Jordan Baker.

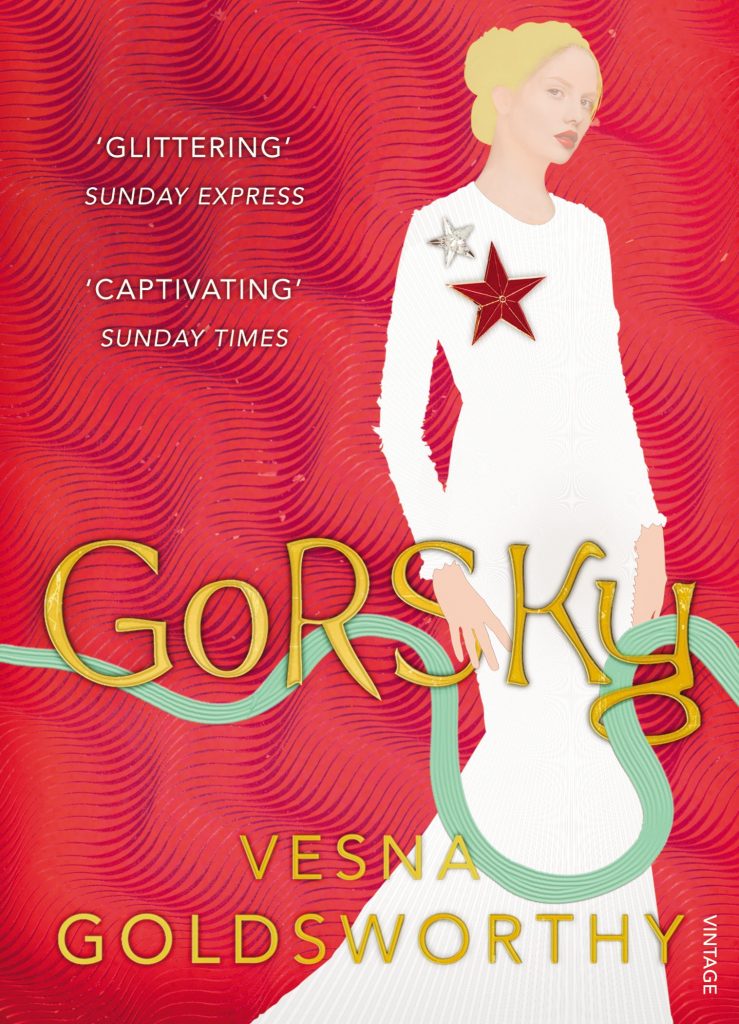

Gorsky is a reimagined version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece The Great Gatsby.

Roman Borisovich Gorsky is one of the richest men on earth; a Russian multi-billionaire who has bought a huge former barracks in Chelsea and is having it converted into the luxury home of all luxury homes.

It is no coincidence that the barracks are situated opposite the merely high-end luxury home of the love of his life. Natalia — ‘one of those willowy Russian women who was so tall and so beautiful that your heart missed a beat when she entered a room’— comes from Volgograd and now lives in London with her daughter Daisy and her husband, Tom Summerscale.

The first-person narrator of Gorsky is a young Serbian called Nick, who rents a small flat in the grounds of Gorsky’s barracks-cum-building site, and makes a meagre living in Fynch’s bookshop, an out-of-the-way place that somehow fits the Chelsea ambience in an English, old-money sort of manner.

Natalia frequents the shop in search of books about modern Russian art. Then one day, Gorsky himself emerges from a long silver Bentley, enters the booksellers, and, with a down-payment in the form of a cheque for a quarter of a million pounds, instructs Nick to acquire the necessary books so that his new home contains

‘the best private library in Europe’.

Not just any general library, but a library tailor-made for a Russian gentleman-scholar with an interest in art, literature and travel, and a flair for European languages; a library that would look as though Gorksy had acquired the books himself and read them over many years, or —if he had not already done so— was fully intending to read them. Moreover, a library that would look as though he had inherited much of its stock from bookish ancestors.

Gorsky, pp. 16-17

Vesna Goldsworthy pays tribute to her Fitzgeraldian inspiration in plot and in names.

In both The Great Gatsby and Gorsky, Nick is the young man, and Tom the husband.

Gorsky is Gatsby, and in case the less literary reader doesn’t twig it, hints are dropped early on. Narrator Nick notes that

… almost from day one, I called him ‘The Great Gorsky’ in my e-mail exchanges with Fynch. My boss was a keen writer of emails in spite of his fusty old Etonian technophobe façade.

Gorsky, p. 14

When the plot-driven necessity for non-English names complicates her contrivance, Goldsworthy finds a way round. Tom’s Russian-born wife could not possibly be called Daisy, so the author gives the couple a daughter of that name. And the Jordan Baker character is a Bulgarian gymnast, Gergana Pekorova; a surname that means ‘baker’ in Goldsworthy’s native Serbian.

Thanks to its great fame, to school curricula, and to the 2013 movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio, familiarity with the plot of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel is widespread. But such familiarity need not diminish enjoyment of Gorsky.

This is no convoluted thriller dependent on unexpected plot twists and surprises. Its strengths lie in beautiful phrasing, bon mots, savvy observations, and descriptions that delight. If you know The Great Gatsby, you will enjoy spotting the knowing parallels.

And from the Russia-in-fiction perspective there is much to relish, even though —a brief trip to a private Greek island aside— the story develops entirely in London.

But, as the novel’s description of a performance at Daisy’s private school illustrates, the geographical setting requires a little elucidation

its pupils were the offspring of international billionaires … Its theatre may have looked like a scaled-down version of the English National Opera, but the audience was anything but English. There were Indians, Arabs, Chinese, Americans, Germans, and even a few Russian women.

Gorsky, p. 165

This is a world that exists on English soil but does not belong exclusively to any particular nationality. Within it the Russian super-rich take their place.

And of course that place has its own distinctives. A multitude of media pieces over the past couple of decades have alighted on themes such as an influx of Russian pupils into élite private schools in England, the buying up of highly expensive property in London (not to mention the luxurious/vulgar/inappropriate modification of the same), and the settling of scores between the Russian nouveaux riches in English courtrooms or — according to the contentions of some at least— in more brutal ways.

Londongrad (2009), a book by the journalists Mark Hollingsworth and Stewart Lansley, sets the scene well from the English perspective. And an unconnected Russian TV comedy series of the same name, first broadcast in 2015, illustrates that the phenomenon of Russians having to deal with life in London is well known in Russia itself. (And incidentally counts among its writers, Owen Matthews, whose novels Black Sun and Red Traitor Russian in Fiction has reviewed).

Part two of this review is here.